THEY fell in love at Jamia Millia Islamia, where they were both students. It was the early ’90s, and they were both studying mass communications. It was also the beginning of the private television channel boom. He was Muslim. She was Hindu. Both families opposed the relationship. To escape them, Suhaib Ilyasi, who would one day host the television show India’s Most Wanted, and Anju Singh, eloped to London. There in 1993 they got married. Anju converted to Islam and became Afsan, and everything seemed set for their ‘happily ever after’.

Except that there was no happy ending to this love story. When the couple returned to India in 1994, all their troubles were resurrected. Anju couldn’t live in Ilyasi’s house and returned to London. According to her brother, she was very unhappy in the marriage and considered a divorce during that time. But she returned to India and a year later the couple had a daughter whom they named Aaliya. Their problems continued and so did Anju’s efforts to leave, this time to her sister’s house in Canada. Ilyasi showed up to coax her back, and in 1998 she returned again to India.

That same year, an idea that the couple had come up with together came to fruition. In their first year together in London, Anju and Ilyasi had been inspired by the British show Crime Stoppers and wanted to create an Indian version of the same show. The two shot a pilot of the show, with the striking and beautiful Anju as the anchor. They were able to sell the show to ZeeTV but when it finally aired in March 1998, it was Suhaib Ilyasi who would be the anchor. The show, India’s Most Wanted, would make him famous. After its initial run of over 50 episodes, ZeeTV renewed the contract. Their idea had been a hit.

Many abusive men who drive their wives to suicide are not believed to be culpable in their deaths.

Their marriage, however, remained a flop. In 1998, not long after the show first aired, troubles prompted Anju to return to Canada again. The same cycle of separation and reconciliation followed. Relatives alleged that Ilyasi would harass Anju that her family had not provided enough of a dowry. In the February of 1999, Anju returned to India again, convinced this time by Ilyasi’s promises of a new apartment. They did buy a new apartment and spent 10 months redecorating and renovating it. The plan was to have a huge housewarming party on Jan 16, 2000, Anju’s birthday. The celebration would never happen.

On the evening of Jan 10, 2000, police were called to the couple’s apartment in Delhi. There they found Anju stabbed to death. Ilyasi said she had committed suicide and that he had tried to stop her by grabbing the knife. This was the beginning of a murder investigation that would last over 17 years. There would be differing autopsy reports; one insisted that homicide could not be ruled out. There would be divergent evidentiary analysis; one stated that Ilyasi’s fingerprints could not be found on the knife despite his own admission that he had tried to grab it from Anju as she tried to stab herself to death. Then there was the dubious manner of the death itself; people who commit suicide rarely stab themselves, and they almost never stab themselves twice. Anju had multiple stab wounds.

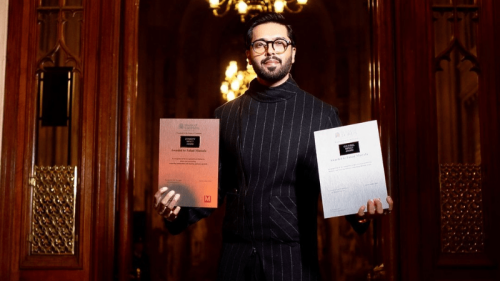

Last week, Anju’s family, which had been subjected to hearing after hearing, arguments, and a custody battle over the couple’s daughter, finally got some justice. Ilyasi, ironically the host of one of the most popular Indian television crime shows, was declared a criminal himself and found guilty of his wife’s murder. A man whose livelihood was to urge the apprehension of other criminals was finally imprisoned himself.

The high-profile nature of the Ilyasi murder case has meant that it has received a lot of attention. Many of the factors defining the case, however, are not altogether unknown in Pakistan and India. A couple fall in love and fail to get family support for their marriage. They get married anyway but once married the power dynamic between the two changes. In this particular case, while the two had come up with the idea of the show together, it was Ilyasi who hogged the limelight and left Anju at the sidelines.

Unlike an arranged marriage, this one did not have two families rooting for it and remained fragile and became ultimately murderous. That is not of course to say that arranged marriages are not abusive marriages. The harassment over dowry, the hostility of in-laws, are all factors that have plagued even those marriages that have had the blessing of both the families concerned.

Then there is the murder that took an innocent woman’s life. In this case, the high profile of the husband likely ensured greater attention for the investigation. In most other cases, the cover story of suicide is easily believed by police and by family members. The fact that a large number of abused women are understandably severely depressed and fed up of the tribulations of their existence makes investigations unlikely and rare. Another ignored dimension is the fact that many abusive men who drive their wives to suicide are not believed to be culpable in their deaths even while being the primary cause of it.

All over the world, in poor countries and in rich ones, murder by an intimate partner is a leading cause of death for women of childbearing age. High-profile cases like Ilyasi’s are windows through which we can see the dynamics inside so many homes and so many marriages. Ilyasi, wife killer, may finally be in prison but many others roam free, harassing and beating and intimidating and abusing, in plain sight, while the world looks the other away.

The writer is an attorney teaching constitutional law and political philosophy.

rafia.zakaria@gmail.com

Published in Dawn, December 20th, 2017