Munnu Bhai was a master in the art of drawing his friends’ portraits, often not meant for publication, and that makes the task of writing about that gem of a friend more than ordinarily difficult. Besides, many people claim to have known him thoroughly well but, in fact, they did not know him well enough, for he was more of a wide-awake person than he appeared to be.

I cannot recall when I first met Munnu Bhai, but it seems to have been decades ago — perhaps as a fellow trade unionist in the 1960s. He had a penchant for contributing to union affairs (Rawalpindi Union of Journalists and Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists) more nonchalantly than the louder orators in the flock, and he was respected for his capacity to act by his conviction regardless of pulls of friendship that he knew how to save.

He became famous as a playwright and was proud of his success and although he acquired the broad grin that became a permanent feature of his sparkling face, he retained his diligently cultivated modesty. To me he seemed to be in a hurry to get on to the next plot as soon as a serial was completed. But he would be at his best while reciting his translation of Palestinian poets, particularly Mahmoud Darwesh.

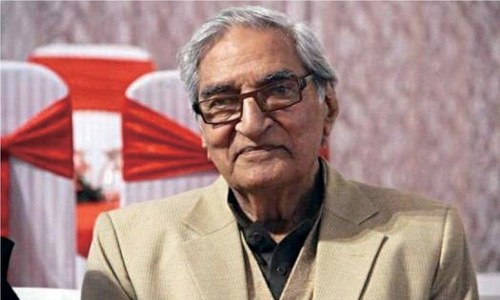

Recounting the times spent with the veteran columnist, playwright and poet

Later on, he developed a racy style of reciting his Punjabi poems and learnt to control his stammer that he earlier on often used for effect. His smile would become wider whenever he was asked to recite his poem Ajay Qiamat Nai Ayee. And while reciting Ehtesaab De Chief Commissioner Sahib Bahadur! the anger in his voice would offer a measure of his contempt for the nabobs in officialdom.

I also discovered Munnu Bhai as one of the Cambellpur (now Attock) cavaliers through Malik Mohammad Jafar whom I was privileged to get acquainted with while editing his elegantly composed articles for The Pakistan Times. Both of them were rationalist, reformist nationalist young men who were sharpening their wits under the guidance of Dr Ghulam Jilani Barq, the author of Two Qurans, and Prof Ashfaq Ali Khan, who wanted Pakistan to become a strong world power by establishing a steel mill.

Munnu Bhai’s association with the Wazirabad rebels, especially Shafqat Tanvir Mirza and Masudullah Khan, also dates to this period. But it seemed to me that while Munnu Bhai shared the passion for change with his companions, he stayed with the pack only up to the point where an alley enabled him to escape into less intense and more romantic pursuits.

I can better recall my association with Munnu Bhai from 1970 onwards when both of us were working for the Progressive Papers Ltd. The information minister in Yahya Khan’s government, Gen Sher Ali Khan, could not bear the barbs Munnu Bhai shot at the regime and ordered his transfer to the Multan office of Imroze. Munnu Bhai wanted to have my opinion on how to deal with what was certainly a crisis for him. He looked worried, so I tried to cheer him by reminding him of the availability of good friends in Multan, in addition to the jagat [universal] friend Masood Ashar, the editor of Imroze. The idea was to survive to be able to fight for another day. It is only recently that I learnt of his lonely sojourn at Multan for two years until Zulfikar Ali Bhutto came into power. But he kept growing at Multan.

Munnu Bhai was one of the earliest converts to the PPP creed but his elbows were less strong than those of some others. He did develop a strong friendship with Hanif Ramay who got him into Musawaat. I missed his company in those days except when I occasionally took Saleem Asmi or some other friend to his Rajgarh home that he kept open to a variety of visitors.

I had a feeling that he was not with me when I told the newly-appointed chairman of the National Press Trust (NPT) — a Bhutto friend — that now was the time to make NPT papers independent, but I admired his openness to conversion when he later on told me, “We should have been more thoughtful while choosing NPT chiefs.”

He could take a joke about himself. When his 50th birth anniversary was celebrated in Lahore, the master of ceremonies was the irrepressible Dildar Pervez Bhatti. He spun a yarn about Quaid-i-Azam’s having recognised Munnu Bhai’s qualities, even when he was a child and hiding behind a tree. Nobody laughed louder than Munnu Bhai.

Munnu Bhai flowered after Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto became the prime minister; he also became closer to Begum Nusrat Bhutto than he perhaps ever had been to Z.A. Bhutto. This connection attracted a good number of fortune-seekers, while he helped an advertising company get rich. As for himself, he enjoyed entertaining a large number of friends, including myself. He enjoyed his meal but liked holding his glass better as he regaled his friends with stories of adventures and encounters in distant lands. Usually very chaste and correct in his speech he was not shy of a match in ribaldry and of putting a dressing of smut on his tales. During this period I was amazed by his capacity to remain friendly with people who spoke against one another all the time. And he could be friendly with fellow poets, too, with Kishwar Naheed occupying a special place in his heart.

I can better recall my association with Munnu Bhai from 1970 onwards when both of us were working for the Progressive Papers Ltd. The information minister in Yahya Khan’s government, Gen Sher Ali Khan, could not bear the barbs Munnu Bhai shot at the regime and ordered his transfer to the Multan office of Imroze. Munnu Bhai wanted to have my opinion on how to deal with what was certainly a crisis for him. He looked worried, so I tried to cheer him by reminding him of the availability of good friends in Multan, in addition to the jagat [universal] friend Masood Ashar, the editor of Imroze.

His love of discovering new outlets for his large-sized talent led him to join Shireen Pasha in making films — docudramas they called them — on environment, and I found Munnu Bhai spending hours trying to master this relatively new craft.

He had seen the rough side of life in his youth and there were problems even after he appeared to have settled down in comfort. But he was more interested in helping anyone who sought his help than telling his friends of the pain in his heart. Happiness came to him when he had grandchildren; it was then that he garnered the joys of childhood he himself had missed.

When Munnu Bhai joined the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan as an elected member of its governing body, I too was working there. I had the opportunity of learning more about his devotion to the causes of the under-privileged. The sympathy for the poor and the disadvantaged, victims of police excesses and ruthless patriarchs that he revealed in his columns was nothing compared to his outpourings as a human rights campaigner.

I can recall the days when Munnu Bhai worried little about his appearance, except for experimenting sometimes with how his glasses should hang on his chest. But then he acquired a taste for sartorial distinction, always appearing in public in a Western suit — often three-piece. Perhaps this was the result of his joining South Asian Free Media Association (Safma) as its provincial head. Alam Gillani fell in love with him and served him well through his hard times.

During the last couple of years, he suffered from one disease or another. It was through sheer willpower that he could drop in sometimes at Nayyar Ali Dada’s monthly baithak or drive to Islamabad to display his wit at Kishwar’s cost, but it was a much diluted Munnu Bhai that we saw. He started reading his verses from published copies and could be heard saying “yaad nahin” — this was coming from a poet who used to recite his poems from memory for hours. His poor health made him depend on his handlers and supporters. They served him with devotion and also started deciding what he should or should not do. They offered no foil to his creative thinking. Yet, he tried bravely to smile till the last moments of consciousness.

What a fighter, my friend Munnu Bhai!

Published in Dawn, EOS, January 28th, 2018