“I met my husband on Tinder,” laughs Mehreen, 28-years-old and a successful human rights lawyer. “But we don’t tell people that,” she is quick to add. “We tell the world we were set up on our first date by mutual friends.”

Like a lot of younger Pakistanis, she was introduced to the dating application while studying in college in the United States. “When I started, it was more for entertainment, to see what’s out there,” she relates. “I didn’t take any matches in the US seriously. Over there, Tinder means something completely different.” Mehreen adds that abroad it is seen more as a means for a casual ‘hook up’ than a modern hip mobile-friendly version of shaadi.com

Mehreen’s intentions may have been ‘honourable’ — as a college-educated, free-thinking woman, she wanted to close this ‘final’ chapter and meet someone on her own terms to spend her life with — but in Pakistan, there are hardly spaces (outside of co-educational institutions and the workplace) for young single individuals to mingle and meet new people and get to know one another. For those that want to go beyond their immediate social circle and cast a wider net, so to speak, there are hardly any spaces that allow that. Being more independent-minded, and aware of what they want and the world around them, they do not want to go down the arranged marriage route.

Popping up to fill that gap are dating apps — Tinder, Bumble, Gindr (for the ‘alternative’ community) etc. But turning to the electronic medium to find a match isn’t anything new. Before the popularity of the smartphone and the emergence of dating apps was the good ol’ shaadi.com, OkCupid.com (more popular abroad), randomly commenting on someone’s profile on Orkut and hoping they talk back to you or, even older, joining chat groups on mIRC and making friends online and having endless chats on ICQ before meeting in person.

A journalist enters the world of dating apps that are transforming singles’ lives in Pakistan

The point being that young people will always seek out and find spaces to connect with others, but in Pakistan, a major difference is that most of that ‘space’ is online. That having transitioned from your computer to your mobile phone, information about your potential ‘friend’ is condensed to a series of photos and one-line descriptions.

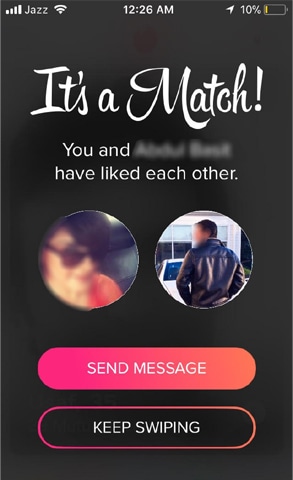

Using just that you decide to swipe left (rejected) or right (accepted). You can’t get a medium that’s shallower than this. The net can’t get cast any wider and rejection is swift and easy.

“Does Tinder even work in Pakistan?” I was asked grumpily by Taimur, a 35-year-old entrepreneur. “I deleted it because it just didn’t seem to work.” Although Taimur is very talented, has many interesting hobbies, is successful in his career and actually a very nice guy, let’s just say he’s not exactly … Fawad Khan. His lack of matches is most probably because of how he is presenting himself.

I came on Tinder a couple of years ago partly due to research into a project (now completed) and … curiosity. I came across a few of my friends (we either ignore the fact that we know the other is using a dating app or tease each other mercilessly) and some people I knew who were married and/or committed (I’m willing to give them the benefit of the doubt that it was curiosity that brought them there). Most amusingly, I came across quite a few people who put up their wedding photos, or photos with their poori family (biwi and bachey) and also, individuals who are clearly very conservative and very religious (as depicted by their beards, prayer marks on their foreheads and the ‘I love Allah/Islam’ description in their bios) but inexplicably active on a … dating app. One wasn’t sure if they know what Tinder is or if they are treating it like any other kind of social network.

Tinder in Pakistan also has its own seasons. Winter is when expats, and Pakistani students studying in foreign universities, return to the motherland. And they bring their active Tinder accounts with them. Suddenly, every other profile has a photo of a Pakistani man in his 20s ‘partying it up’ with at least one or two token goras — to score full ‘exotic’ points.

I also discovered that people in different cities posted similar types of photos. In Rawalpindi and Lahore, for some reason, every other man is a ‘Raja’, ‘Chaudhry’ or ‘Sheikh’ and they love posing with their sunglasses on and in front of their cars — as if the cars are equally responsible in testifying to their virility and prowess as a potential match in their photos. Another interesting aspect of using Tinder in Lahore was that you end up seeing a lot of profiles from across the border — the app brings you matches based on geographical proximity.

And then Tinder in Pakistan also has its own seasons. Winter, especially around Christmas break, is when expats and Pakistani students in foreign universities return to the motherland to spend time with family, attend weddings, bring their friends to show the country off etc. And they bring their active Tinder accounts with them.

Suddenly, every other profile has a photo of a Pakistani man in his 20s ‘partying it up’ with at least one or two token goras — to score full ‘exotic’ points. Some might even be showing off some of the haram habits they’ve picked up as a sign of their (late onset adolescent) rebellion and independence. They desperately want you to see them for what they think they are: emancipated adults in their own rights. So, what if their studies (and lives) are funded by their parents? They might not even give a full one-line description, but they will always — always — list the foreign universities they have been to or are currently enrolled in.

If you thought your phuppo was a bit over-the-top showing off her foreign-returned beta for his pick of eligible matches at a relatives’ wedding, you haven’t seen the swag displayed by these same ‘eligible bachelors’ online. I can tell you one thing for sure: if phuppo saw their profiles, she would not approve.

“It’s been very good for my ego,” confessed Danish, 31-years-old, chartered accountant from an otherwise conservative family in Karachi. Danish went on the app after a very long relationship with a woman he desperately wanted to marry didn’t end up with them saying qubool hai. He was completely shattered but, instead of drowning his sorrows in food and Netflix, he hit the gym and ... Tinder. In that order. And he’s been quite successful — he’s met some very nice people, some he is good friends with, his social circle and exposure to the world has expanded and he’s learned to base his sense of worth on who he is, rather than who he’s with. Is he now ready to settle down? “No,” he was quick to respond. “I’ve realised there is more to the world than that. Maybe someday, but not now. The risk of using Tinder in Pakistan is that women use it to find … husbands. You have to be very clear that you just want to be friends.”

While it’s hard getting a hold of Tinder stats in Pakistan, across the border in India, the popular dating app even has its own official physical office with its own she-boss: Taru Kapoor.

According to a section of the Indian press, one million ‘Super Likes’ — an indication on Tinder of intense interest in another person — are sent in India each week, with women sending Super Likes more often than men. The app empowers women, according to Kapoor, since women cannot be contacted by men they are not interested in. You can only contact one another if both parties mutually express an interest. Hence no unwanted advances.

It’s popular as well. According to a report published by the Press Trust of India, in 2015, the number of downloads for the app in India increased by 400 percent. The application is currently present in 96 countries and claims to have made nine billion matches worldwide. A massive shift in societal and cultural values in India, where women want to be more in control of who they choose to be with, is attributed to them taking the more ‘bolder’ first step.

But coming back to this side of the border: “Are there a lot of escorts in Pakistan?” I was asked by a gora backpacker friend henceforth referred to as Tim (34-year-old, engineer). Not that I would know, I responded. “I went on Tinder and some of the profiles … with the kind of photos they’ve put up of themselves, these women give the impression that they’re escorts,” he elaborates. “It’s very common to find them on dating apps in the United Arab Emirates. And usually the first message they send you after you’ve matched with them is how much it will cost you to spend time with them. It’s disillusioning and gross, especially if you’re only looking to meet people. Instead you come across women who see you as an ATM.”

“There are a few weird women out there,” agrees Ahsan, 37-years-old, artist. “I can’t put my finger on it. On paper, they’re educated. In their photos, maybe they’re a bit much. Too much makeup, look a bit wild etc. In person, they’re very nice and can carry a light conversation. But I’ve realised, they’re not really interested in getting to know you as a person. Or even connecting. They’re just happy as long as you pay for them — food, groceries, pick/drop, drinks, entries to parties and events etc. But that’s it. That’s where the ‘connection’ ends.”

“They’re escorts,” affirms Tim. Really? “Yes,” he said. “There is no exchange of money, but rather of gifts.”

But it’s not all dark and murky where women are concerned. “I think [this impression is created] because a lot of women are worried about putting their own photos out there,” says Adam. “In case they get caught aur log kya sochay gey [what will people think], you come across a lot of profiles with fake photos and names — Kareena Kapoor ki photo daal di, naam bhi ‘Princess’ type rakh liya [put up a picture of Kareena Kapoor, called yourself something like ‘Princess’].” One isn’t sure what what they’re looking for. Maybe it’s just the thrill of seeing what’s out there — after all poondi (Punjabi slang for when you ogle at people and sometimes undress them with your eyes. It can be very uncomfortable being the object of a poondi gaze) is a national pastime.

Farhad, 41-years-old, freelance artist, provides a more ‘rounded’ look of Pakistani women on Tinder. “There are two types of women,” he says. “One is the older post-30s lot, often divorcees, who are more forthright about what they are seeking — mostly love and companionship — and then there are the younger university-type students who seem more coy or unsure. Interestingly, most of the women whose profiles I’ve come across are not the ‘burger’ types,” he says referring to slang for upper-class English-speaking people. “Given how difficult it must be for them to meet outside their college environs with random men, I would think they are primarily interested in a phone or texting relationship at least to begin with.”

This is all very insightful, but before we start tut-tutting this as a western conspiracy to corrupt our youth (and mature adults, seeing most that we spoke to are close to or past the 30-year mark), it’s pertinent to point out that a bunch of savvy Pakistanis came together and created their own local dating app — aptly titled PoondiApp. Pure genius and 100 percent Pakistani, but phuppo may still not approve.

It’s currently only available on Android phones and is proud to be the first made-in-Pakistan dating application. According to them, “It’s a fun way to meet new and interesting people around you, see where they are in real time.” That last bit might be a bit too much and could encourage stalking. But the app-developers are unfazed. “Our aim is to make dating easy and socially acceptable in Pakistan.” Judging by the rapidly increasing popularity of foreign dating apps, clearly they feel there is a demand out there for a local one.

The writer is a member of staff.

She tweets @madeehasyed

Published in Dawn, EOS, February 11th, 2018