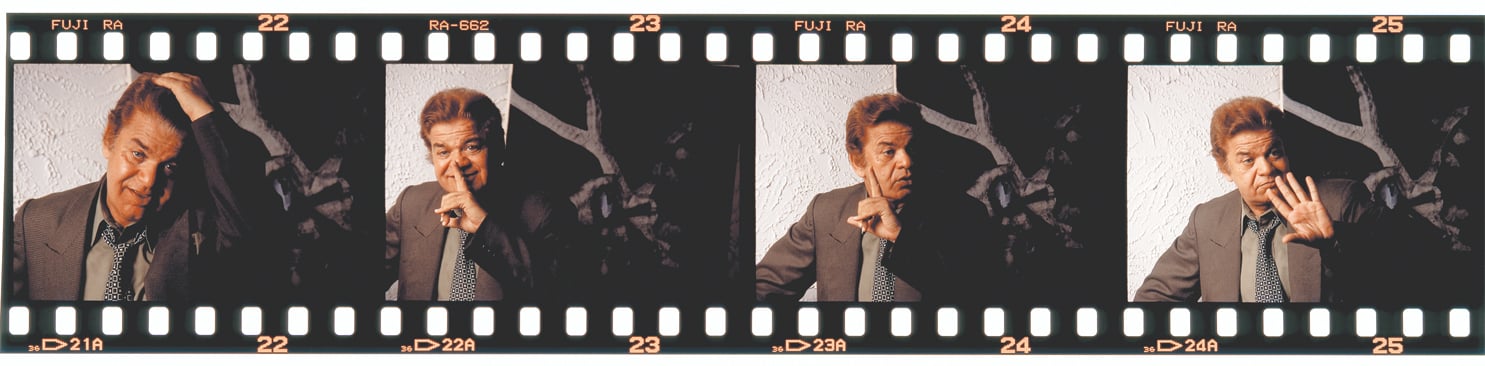

Qazi Wajid was a born actor. And until his last day, which came about as suddenly as a piece of shock-drama that he usually eschewed with superb nuance, he was still acting. In fact, it was quite rare to see him as a normal, everyday man outside of his screen performances. But such was his charm and style that people loved him for the performer he was. In his unexpected passing, I have lost a very, very dear friend.

Qazi Wajid began his career in front of the camera from the age of 10 as one of the boarding school boys in one of the earliest Pakistani movies in the mid-1950s, Beydari, which featured the now-famous song Aao bachon sair karaayein tumko Pakistan ki. Later he became a full-time artist at Radio Pakistan in Karachi, contributing to various programmes, and many still remember him as a regular voice artist for the very popular Cassette Kahaniyaan for children.

He began his radio stints in late ’50s as a performer in the Sunday morning show for children Bachon Ki Dunya, which initially had Abdul Majid as an anchor and later Munni Baji. In the segment titled ‘Qazijee Ka Qayda’ Qazi used to play a student attempting to learn his lessons and often being admonished and beaten by his ustaad. As a student of Class IV, I once attended the recording of the show with my neighbours (including Shaukat Aziz, who would go on to become Pakistan’s prime minister) and sisters and I remember us rolling over in laughter at the shenanigans before us. Later Qazi Wajid would turn up at our school to perform the skit on one of our annual commemorative days. That was when I became his ardent fan. Little did I know that, decades later, I would be performing with him in television plays.

The veteran actor, who passed away on February 11, was more than just the consummate everyman actor

My first ever appearance with Qazi was due to my friend Ishrat Ansari at PTV Karachi in 1967-68 when, as a director, he teamed me as a lead with Qazi Wajid for Hijab Imtiaz Ali’s Toofani Dopaher [Stormy Afternoon] which also included Masooma Latif (nee Shah) and Santosh Russell. We had been buddies since then.

Like my father Jamiluddin Aali’s closest friend from college days — the poet Akhtarul Imaan — was 10 years elder to him, Qazi Wajid was 10 or more years elder to me, but we came to believe that we were of the same age and he became one of my closest friends. He could always be counted upon to have me in stitches with his spontaneous sense of humour and understated wit — which sometimes became a problem during recordings when I needed to deliver lines in all seriousness. Inevitably if you asked him ‘Kaisay ho? [How are you?]’ his stock reply would be ‘Main tau hamesha se achha hoon [I have always been good]’. He also loved to add his own interpretations to his lines. His ad-libbing, rather than being an irritant, however, was often appreciated by his directors, because it would add to the texture of his characters.

His funny bone was on display at all times. I recall one episode off the sets in particular. We had gone to shoot a play in Scotland and after our shooting was done he insisted that I take him around the UK since it was his first time there. So we caught a double-decker bus to Blackpool to spend a few days at my cousin’s. Qazi had a craze for good clothing and one day, passing by the town centre’s commercial area, Qazi spotted a tie he liked and we went in and asked for it. The pretty sales girl looked at Qazi and told him that he looked like an actor. I was actually astounded and asked the salesgirl how she had guessed that Qazi was a very famous actor in Pakistan. She replied that she’d guessed from his looks and the twinkle in his eyes.

As the salesgirl left to get the tie, Qazi — who was not very conversant with English — turned and asked me “Kiya keh rai hai ye bacchi? [What is this girl saying?]” I explained our conversation and when the girl returned with that beautiful tie, Qazi took no time in saying “You actress also!” and she laughed like anything.

Now this didn’t end here because Qazi Wajid was indeed Qazi Wajid. Upon glancing at the price tag of the tie — it was listed for 80 pounds — Qazi spontaneously told her “I want tie, not Taj Mahal!” The salesgirl shrieked with laughter and called her colleagues over to meet this witty actor from Pakistan. When they all gathered, he told them in Urdu that since the salesgirl was more beautiful than the tie, so out of respect for her he would not buy the tie, which I had to translate for them. A roar of laughter was heard and then they said you’ve got to have coffee with us and take a picture with all of us. And that is indeed what happened. For Qazi Wajid, lack of fluency in English could not hold back his innate charm.

His garrulousness and penchant for wit also disguised the utter seriousness with which he took certain things. He was actually very well read and could recite Ghalib, Meer, Zauq, Faiz and my father’s poetry from memory. In fact, he was extremely adept at judging metre and rhyme and could immediately point out when someone recited something off-metre. “There’s something wrong there,” he would point out irritated when someone made an error.

I too was once at the receiving end of such an admonishment. It so happened that while having tea, I was humming one of my father’s couplets. Qazi said to me, “Kursi se utth jao ... aur jab tak sahee sheyr na parrho, beithna matt! [Get up … and don’t sit down until you read the couplet properly!]” I felt cheesed off — after all it was my father’s poetry he was challenging me on — and I insisted that I was reciting it correctly. He gave me a scornful look and said “Abhi Aali sahib ko phone milao ... Meri baat karwao [Call Aali sahib right now and let me speak to him].” I called my dad and Qazi took the phone and said “Adaab … Yeh sheyr jo mein aap ka parrh raha hoon iss mein koi ghalati tou nahin? [This couplet of yours that I am reciting, am I making any mistake?]” And he recited his version of the couplet. Abbu said it was absolutely correct, but asked him why he was reminded of it since it was a very old couplet of his. At this Qazi told him “Your banker-actor son is going wild trying to convince me with a couplet that he is reciting incorrectly.” Of course I never heard the end of it from my father, who himself was an ardent admirer of Qazi’s stage and TV performances.

As an actor, Qazi Wajid could possibly have been one of Pakistan television’s greatest finds. Like Spencer Tracy, he inhabited his everyman roles in so many serials and plays so perfectly that it would be difficult to imagine anyone else having performed them. As the mean husband of Ishrat Hashmi in Bajya’s adaptation of Afshaan, directed by Zaheer Khan in early ’80s, he genuinely made viewers hate him. But perhaps the pick of the hundreds of plays he acted in was his role as a ‘street urchin’ in Khuda Ki Basti, that most realistic saga of the newly created Pakistan’s story of social taboos and rich vs poor. Qazi’s role as Raja, best friend to Nosha (played by Zafar Masood in the 1969 version and later by Behroze Sabzwari in the 1974 version) was remarkable in its realism. In the last episode of the serial, his portrayal of an ailing Raja begging Nosha not to leave him brought tears to thousands of eyes.

But of course Qazi’s talent spanned across mediums. When theatre was still popular, K. Moinuddin’s theatre group made us see Qazi Wajid as one of the stock characters in Khawaja sahib’s blockbuster stage plays such as Laal Qilay Se Lalukhet [From the Red Fort to Lalukhet] where Qazi’s role as Chaghoo the barber will remain in the minds of those who have seen the play on stage and on PTV. Others will remember him as one of the original cast members of K. Moinuddin’s immensely popular satire Taleem-e-Baalighaan [Education for Adults] from the 1960s, which was, in fact, set to make a comeback on stage in a few weeks — with Qazi as the only original cast member still performing.

Having had the taste of the big screen also, Qazi did do a few roles in films as well but these were usually as a sidekick or as a part of typical comedy sprinklers. His real talent that made viewers empathise with his characters only came out in television. He was among that fast-dying breed of performers who took pride in their characterisations and who brought a wealth of experience and literary knowledge to their craft on the screen.

But beyond it all, he was also one of the most genuine and humane of people. And we are all poorer for having lost him.

The writer is a former banker, an actor and the current president of the Anjuman-i-Taraqqi-i-Urdu

Published in Dawn, ICON, February 18th, 2018

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.