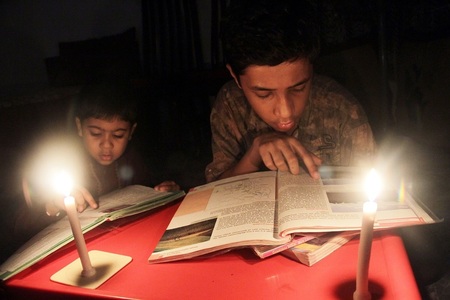

ENDING load-shedding was Nawaz Sharif’s biggest campaign promise, and has been the backbone of his narrative since his disqualification. All through the GT Road march last summer, the main question he asked of his supporters was: ‘Did I not promise to end load-shedding? Has load-shedding not ended in your area?’

One of the most consistent areas of focus for his government has been the power projects that are coming up, as well as the LNG terminals that are supposed to provide the vital fuel to many of them. And now, at the very moment when the ruling party is on the cusp of delivering on that promise and hitting the campaign trail for the next general election, the energy minister has announced that it will take more than more power-generation capacity to end load-shedding.

If recoveries in the power sector are not improved, he recently said in a written statement, and theft and other losses from the distribution system not curtailed, the power sector would be set to rack up losses of Rs360bn, triple of what they were back in 2013 when the promise to end load-shedding was first made. New generation capacity is indeed coming online, but the leakages of the old system remain firmly in place, which means as we pump more power into this leaky grid, we lose more as well.

Read: Zero loadshedding: Election gimmick or lasting solution?

The financial drain that the losses amount to is too large to be met through government resources, the minister warned, meaning it will become necessary to resort to load-shedding in large areas where recoveries remain weak, even though surplus power-generation capacity would be available.

It is encouraging to see the government finally acknowledge that there is more to resolving the persistent power shortages than raw megawatts alone. Reforming the power bureaucracy and improving recoveries to maintain its financial health is equally important. But the problem is that reforms are not high-visibility projects, and afford no ribbon-cutting opportunities; therefore, the government never attached the same priority to them as it did to the power plants coming online now.

This neglect has created an embarrassing situation, where surplus power capacity may be left idle because the funds to operate it are not available. In a sense, when delivering on its campaign promise, the government may have put the cart before the horse by starting off with adding more generation capacity.

Published in Dawn, February 24th, 2018