KARACHI: Despite the fact that both Sindh and Balochistan have banned catching of over a dozen endangered shark species, the top ocean predator is a major by-catch in both provinces.

In Karachi, shark meat is largely consumed as finger fish while fins are illegally exported as “salted dry fish”.

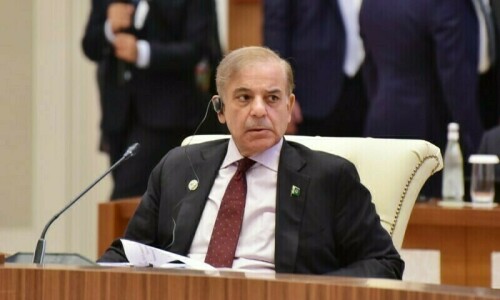

Experts raised these points at a workshop organised by World Wide Fund for Nature-Pakistan (WWF-P) at a hotel here on Monday.

Titled ‘Shark conservation: streamlining trade of CITES species’, the two-day programme was supported by Shark Conservation Fund.

It aimed at creating awareness among stakeholders, particularly government officials handling exports, about shark conservation and their role in this goal.

Highlighting the important ecological role sharks play in oceans, speakers said though the species is mainly caught as a by-catch, it formed an important part of Pakistani fisheries.

“It’s not a targeted species like tuna and shrimps, though the quantity of their catch gets bigger than the targeted fishery in some seasons,” said Mohammad Moazzam Khan who is associated with WWF-P as its technical adviser on marine fisheries.

According to him, the annual production of shark fin is estimated to be between 80 tonnes and 200 tonnes. “We get these figures from countries importing fins from Pakistan or from Traffic (an international network to monitor illegal wildlife trade) as Pakistan lacks a mechanism to document fin exports, often labelled as salted dry fish here.”

Of the 134 shark species found in Pakistan, he pointed out, 18 species were on the CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species in Wild Fauna and Flora) list.

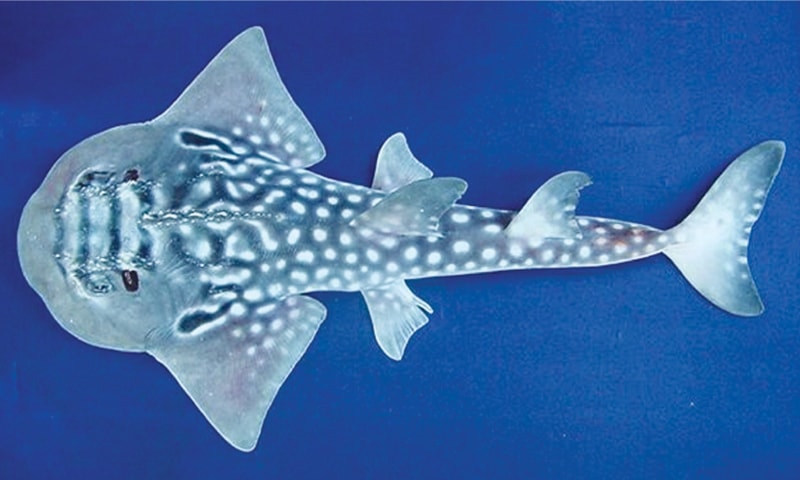

“Only sawfish, a highly endangered species, is on the Appendix 1. The rest are on the Appendix II which means that a country interested in their export has to follow a procedure, which includes formal assurances that the catch didn’t come through harmful methods and that it won’t have a serious effect on the species’ population,” he explained.

The fisheries laws of both Sindh and Balochistan, however, banned catching of all CITES-listed species, he added.

“These species included whale shark, hammerhead shark, silky shark and thresher shark, largely caught as a by-catch in abundance,” he told the audience.

‘Finger fish’

Mr Khan emphasised the need for collecting data at all landing sites, around 74 in Sindh and Balochistan, to help assess the species’ status as well as creating a database on shark fishery.

He was of the view that it was the mandate of provincial governments to keep record of all fish, including sharks, caught at each landing site.

“Shark fins are exported to countries like Philippines, Thailand and Taiwan where they are in high demand. Shark meat, however, is sold to local vendors who sell it as finger fish while its skin is dried and used in poultry feed,” he informed the audience.

Director wildlife at WWF-P Dr Babar Khan underscored the need for learning from other Indian Ocean countries’ experiences on shark conservation.

“It is also important to make fishing communities aware about the important role sharks play in the ecosystem,” he said, adding that Pakistan being a signatory to CITES needed to check illegal exports of shark products.

Manager wildlife at WWF-P Hamera Aisha spoke about the scale and impact of illegal wildlife trade. She also highlighted the efforts her organisation had undertaken to curb illegal wildlife trade in Pakistan.

Ahmed Nadeem, the deputy director of Balochistan fisheries, shared local fishermen’s perspective on sharks and their knowledge about the species.

“Whale sharks have been a non-targeted species for a long time whereas the rostrum of sawfish has a religious value. Fishermen are ready to sacrifice their costly nets for releasing endangered species,” he noted.

Many shark species, it was said, were vulnerable to over-exploitation due to their biological characteristics of low-productive potential and, hence, having limited capacity to recover from overfishing.

The decline in shark catches, experts observed, indicated an alarming trend, which needed to be addressed.

They also emphasised the need for developing a national conservation plan for sharks for which lessons could be drawn from the experiences of other Indian Ocean countries.

Published in Dawn, March 27th, 2018