THE 21st CENTURY: THE AGE OF THE MILLENNIAL

HARMONISE OR GO BUST

Inconsistencies abound along the hazardous path to mastering digital platforms for agencies and brands. Either synchronise capabilities or screw up, postulates Syed Amir Haleem.

It was the mid-eighties in Riyadh. Most kids my age were out playing cricket, but I was busy hacking into a computer game called King’s Quest by Sierra. The official versions of computer games were not available in Saudi Arabia; consequently, the usual hints and support were always missing. If you got stuck, you either waited until you, or someone else, figured the way out.

I chose to hack into the code. With that came the need to transfer a large amount of data between friends and in 1990, I brought home a bulky odd-looking device, called a modem, that would connect my landline telephone headset to the PC. Boom! Just like that, this one, unassuming device ushered all of us into the online digital age.

Although I was only a young kid having fun, it hit me how powerful this could be. I had no doubt it was the future. Yahoo came along in 1994, ushering in the internet for people like you and I.

However, in Pakistan, the internet was mostly a space to experiment in and have fun, and I did not use the internet in a professional capacity until 1996, when I tried to share account management data between the Lahore and Karachi offices of Interflow. Even by 1998, when Google was born, only two other agencies were using digital as a means to communicate.

As a natural progression, IT departments at the client end volunteered to develop websites for their companies and as they were techies, they did the most obvious thing… they looked for technology vendors.

As a consequence, Pakistan’s first digital companies were born from small departments, developing websites within larger software development companies. From thereon, until as late as 2006, two years after the entry of Facebook and a year after YouTube came into existence, it never occurred to anyone how user-unfriendly these websites were.

They were fully functional, but they lacked aesthetics and did not even attempt to make the user experience easy. The flaw was that technology people are very good with coding but useless at design and communication.

In 2008, the multinational companies began to wake up to the opportunity and did the smart thing – they asked their advertising agencies to develop their websites or at the least, design them so that the software houses could build a better user experience.

Oddly, most agency owners failed to spot the opportunity this presented. However, along the way, something happened independently that forced the advertising agencies to look at digital as a viable source of revenue.

Between 2000 and 2010, agency revenues had started to shrink. Revenues from print jobs had gone as clients preferred to work directly with the printing presses. Then came the media buying houses and the agencies lost their commission revenue on media. Finally, as more and more film directors started to work directly with clients, TVC production also went, resulting in the closure of in-agency AV departments.

Desperate, the agency owners looked for anything that seemed like an opportunity and the fact that the software houses were so bad creatively, was a good way to generate some revenue.

Of course, in typical Pakistani agency tradition, they did it in the most unprofessional way. Interns, fresh out of college, were hired to handle their clients’ digital requirements. By 2010, blue-chip companies began to take an interest in social media.

Although the first digital agencies had started popping up in early 2000s, it was not until 10 years later that they began receiving serious business propositions. Along the way, clients experienced many frustrating moments, not least because if the software houses lacked creativity, the agencies lacked technological know-how in equal measure.

It has been a long journey. However, today, the frustration has shifted from the client end to the digital agency end, which, to their credit, eventually managed to evolve at a breathtaking speed. It was the clients that were lagging behind.

Even as late as 2015, 26 years after the birth of the World Wide Web, most clients still thought a digital presence meant only having lots of ‘likes’ on Facebook posts; quite astonishing, considering that the version of the software I am using to write this article will be outdated in less than six months. So imagine the frustration digital agencies experience when their clients are still living in 2006.

So, while during the late nineties and early 2000s, agencies spent much of their time trying to catch up with their clients’ digital requirements, today, the clients are the ones who need to catch up with global trends. And they must do so quickly. There was a time when each country could conceivably choose to adopt technology at their own pace; today, this is no longer practical, simply because the speed in the evolution of technology does not permit this any longer.

What is required is the rapid synchronisation in the digital capabilities of the digital agencies and of their clients in Pakistan.

Syed Amir Haleem is CEO, KueBall Digital. He can be contacted at syedamirhaleem@kueball.com

WILL MAINSTREAM AGENCIES SURVIVE THE ONSLAUGHT OF BIG TECH COMPANIES?

In the digital advertising space, business models for creative agencies are under increasing threat due to the entry of the big technology companies, says Amin Rammal.

An Agency of Record (AOR) is commonly defined as an advertising agency authorised by an advertiser to buy advertising space and/or time on its behalf (businessdictionary.com). While this is still relevant from a media buying perspective, the adaptation of this concept in the creative, strategy and execution space may not be so intuitive in a digitally-driven, highly fragmented communications environment.

The relevance of an offering (AOR or any other relationship) depends on what the customer (advertiser) needs. The traditional agency model was a strategic partner relationship with the advertiser to manage their brand communications providing strategic planning, creative idea generation, production, execution and media planning and buying.

The AOR has been a prerogative of multinationals and large national clients. In Pakistan, multinationals adopt brand strategies developed at the global or regional level, with an aligned AOR. Major thematic campaigns are beginning to move in a similar direction, where the trend is towards global and regional creative.

So the selection of AOR agencies by multinational clients is based on regional or global agency alignment. The local agency affiliate is more execution or tactical focused. It is unlikely that this will change in the near future as multinationals are able to better synchronise and manage cost with globally or regionally aligned AORs.

Very few local advertisers invest in strategic planning and the focus tends to be more on execution. In many cases, large local advertisers appoint AORs, but the selection is often driven by price or triggered by new decision-makers in the marketing department. They also tend to maintain flexibility by keeping a roster of execution agencies.

In Pakistan, similar to the rest of the world, media planning and buying has become a specialised area thanks to the advent of media buying houses. Whether an advertiser selects a full-service agency or a media buying house to plan or buy media, economies of scale support the consolidation of media buying to a single or few entities. Hence the support for AOR in case of media, continues to stand for now.

However, some media buying houses are offering creative services, particularly in the content area, by partnering with content producers or smaller creative agencies. While they act as a single AOR for the advertiser, they are forward integrating with smaller entities and freelancers.

There are different permutations of AORs when dealing with specialist areas such as mass media versus digital, versus PR, versus activation. The decision is driven by the advertiser’s legacy system, the organisational structure and capabilities, the agency’s offering in the marketplace (full-service versus specialisation) and the cost structures of the industry.

Although in the short term, the AOR model seems to be working in Pakistan with different variations, the debate brewing globally is will the concept of AOR continue as digital’s share of advertising grows? The answer depends on several factors.

In the good old days, the agency was perceived as the expert on consumer behaviour, a reservoir of creativity and the shrewd negotiator making deals with different media owners on behalf of their clients. A centralised role was important to synergise at least parts of the advertising value chain.

Currently, it seems agencies, at least in developed countries, are going through a midlife crisis experimenting with various business models and flirting with technology companies, while soul-searching to identify who they are. What is causing this?

The likes of Google and Facebook have changed the traditional advertising model. Google has consolidated the majority of website content publishers and Facebook provides a platform for user-generated content to be monetised as media.

The inherent advantages the big technology companies have is their ability to provide the following: centralise negotiations and serve ads through their networks despite the exponential increase in content publishers; seamless content integration through the likes of YouTube or Facebook fan pages; designated representatives to work with large global agencies and advertisers and offer direct advisory services in local markets to better plan their media spends with them; improved customer insights through unprecedented data on users, which they can crunch in real-time and deliver to advertisers and agencies through user-friendly interfaces and predictive capabilities, deploying algorithms to target and engage consumers.

While AORs are common in traditional advertising, they are not necessarily the dominant arrangement in digital. Digital savvy advertisers are developing their own online assets that can be managed internally, or by the agency which either comes up with the idea, or is best equipped for it: AOI (Agency of Idea) versus AOR (Agency of Record).

The impact of digital is also evident on the advertiser side with ‘The Rise of the Chief Marketing Technologist’ (source: Harvard Business Review, Jul-Aug 2014).

According to the article, “CMTs are part strategists, part creative directors, part technology leaders and part teachers; they champion greater experimentation and more agile management of that function’s capabilities.”

Is the AOR relevant in the fast-paced digital, ideas-driven world? If media planning and buying is being simplified at the tail-end of the communications value chain and a CMT is in place on the advertiser’s front, what services will the agency of the future provide?

Global communications groups are hedging their bets by investing in technology-driven companies with different areas, including data analytics and insight, digital creative agencies, ad serving networks and content platforms, including e-commerce sites.

WPP’s recent investment in AppNexus and Publicis’s interest in Criteo are evidence of their foray into data and technology to provide alternatives to Google and Facebook’s ad serving capabilities.

Which of the bets by the global communications will pan out is the billion dollar question. Whether the ad agency networks will be successful in maintaining AOR status quo in the digital age through its acquisition of technology companies is uncertain.

In the short-term at least, the global debate on AOR is less likely to impact Pakistan given the dominance of traditional media. However, in an increasingly digital world, global trends are likely to disrupt the local scenario.

Article excerpted from ‘Of the record or of the idea?’, published in the November-December 2014 edition of Aurora.

Amin Rammal is Director, Firebolt63, The Brand Crew and APR. He can be contacted at amin.rammal@firebolt63.com

YOUR BRAND’S BEST FRIEND

Syed Ali Hasan Naqvi on why print advertising continues to effectively deliver results in an age of new media disruptions.

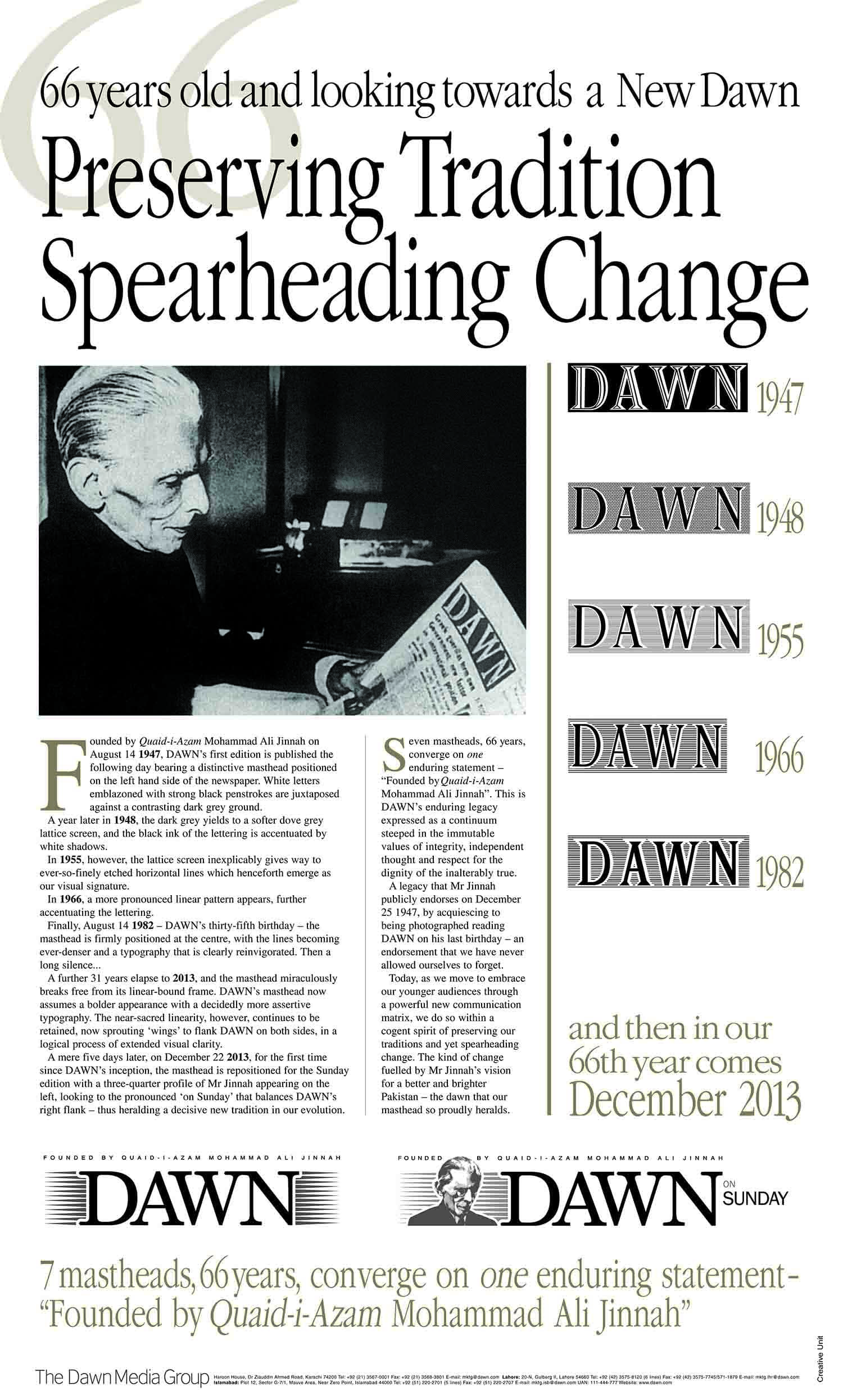

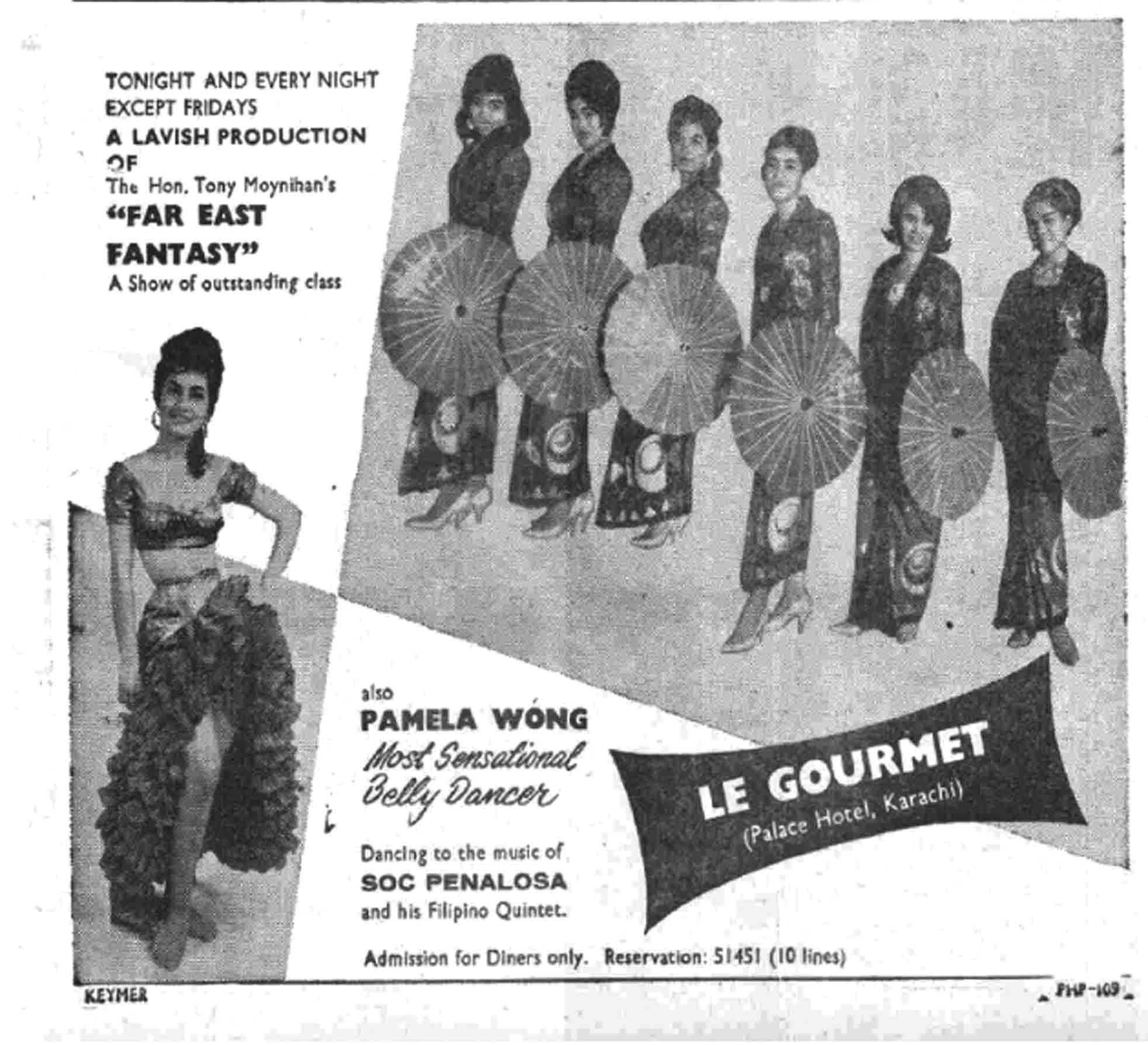

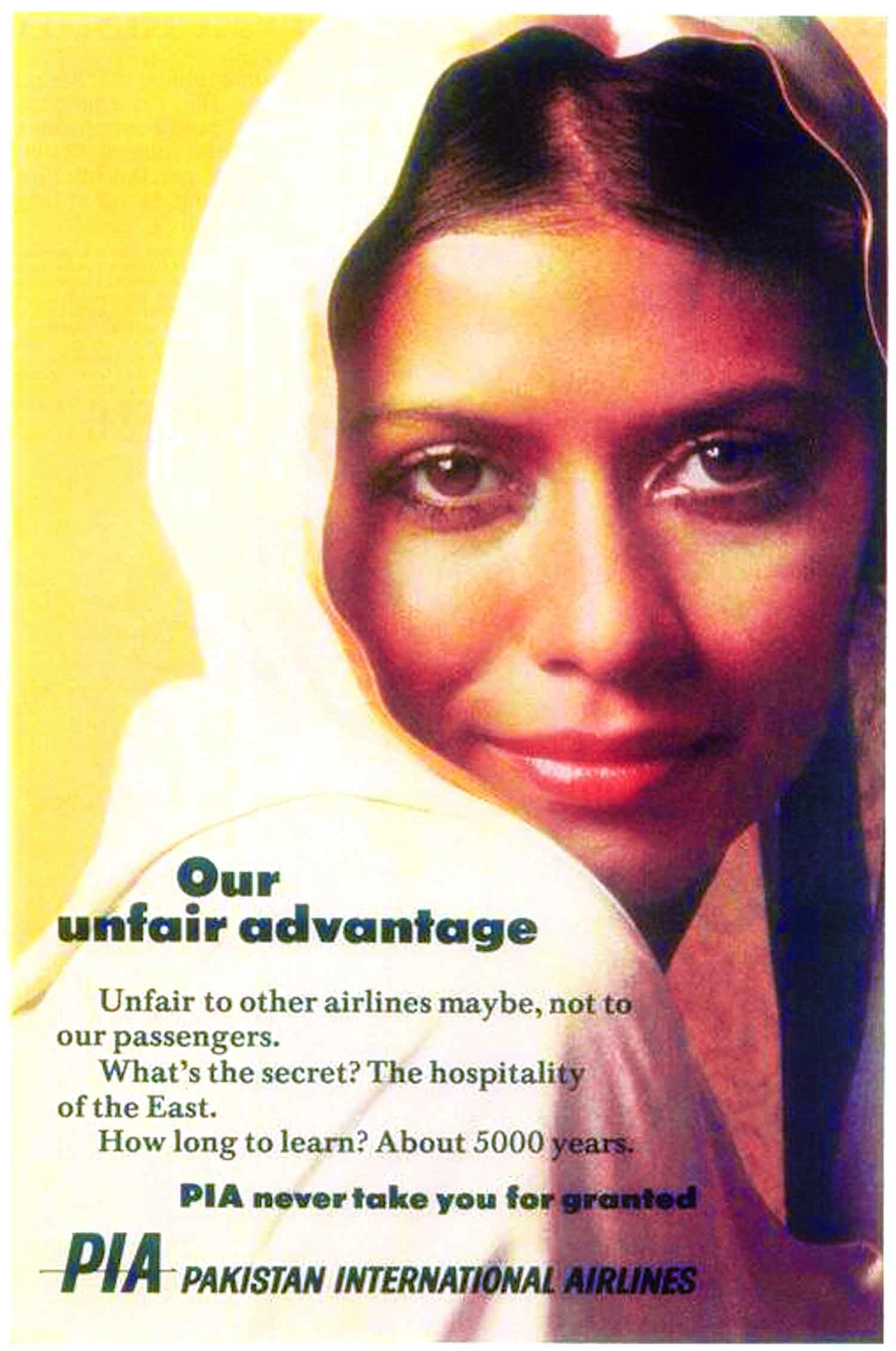

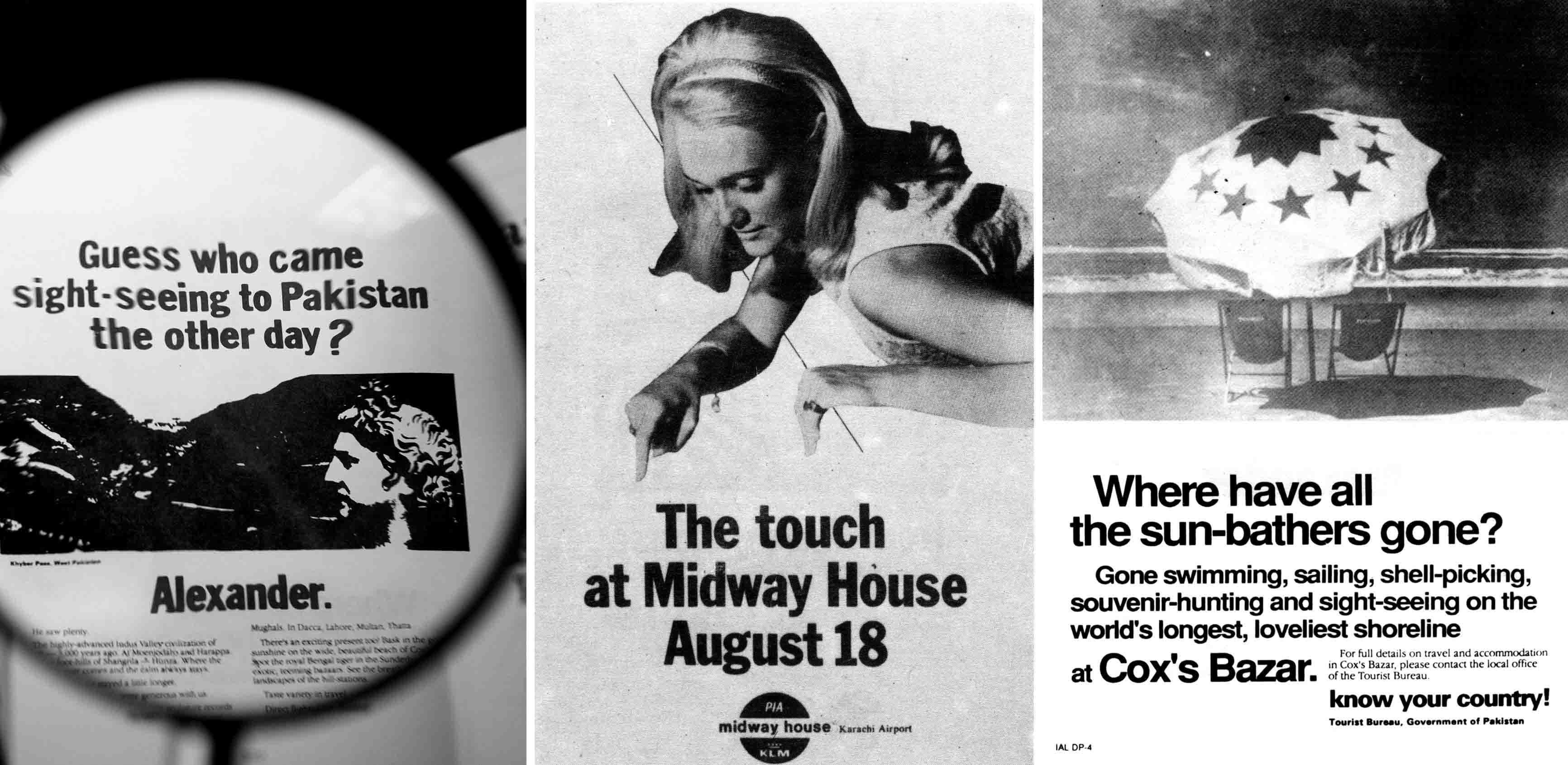

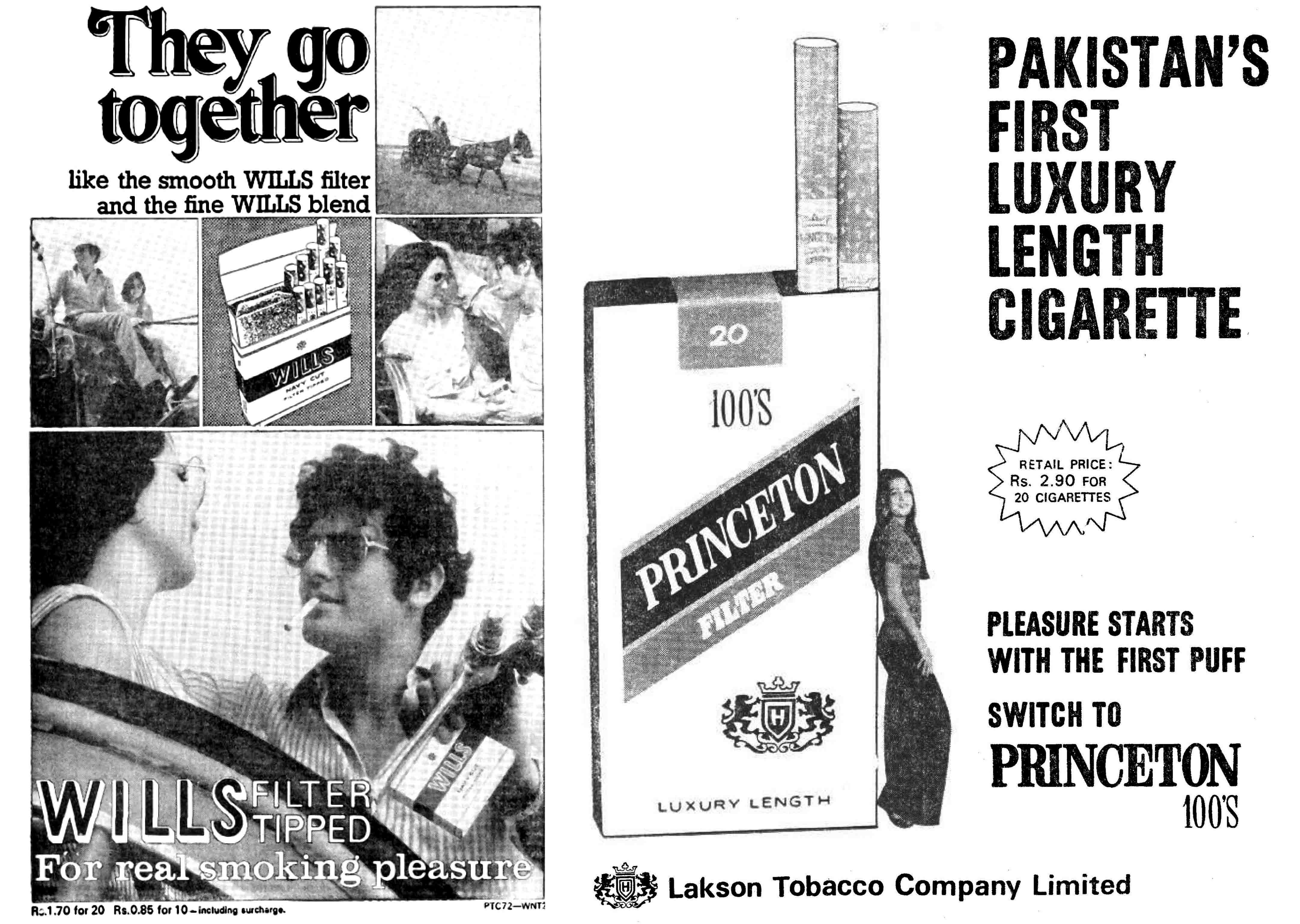

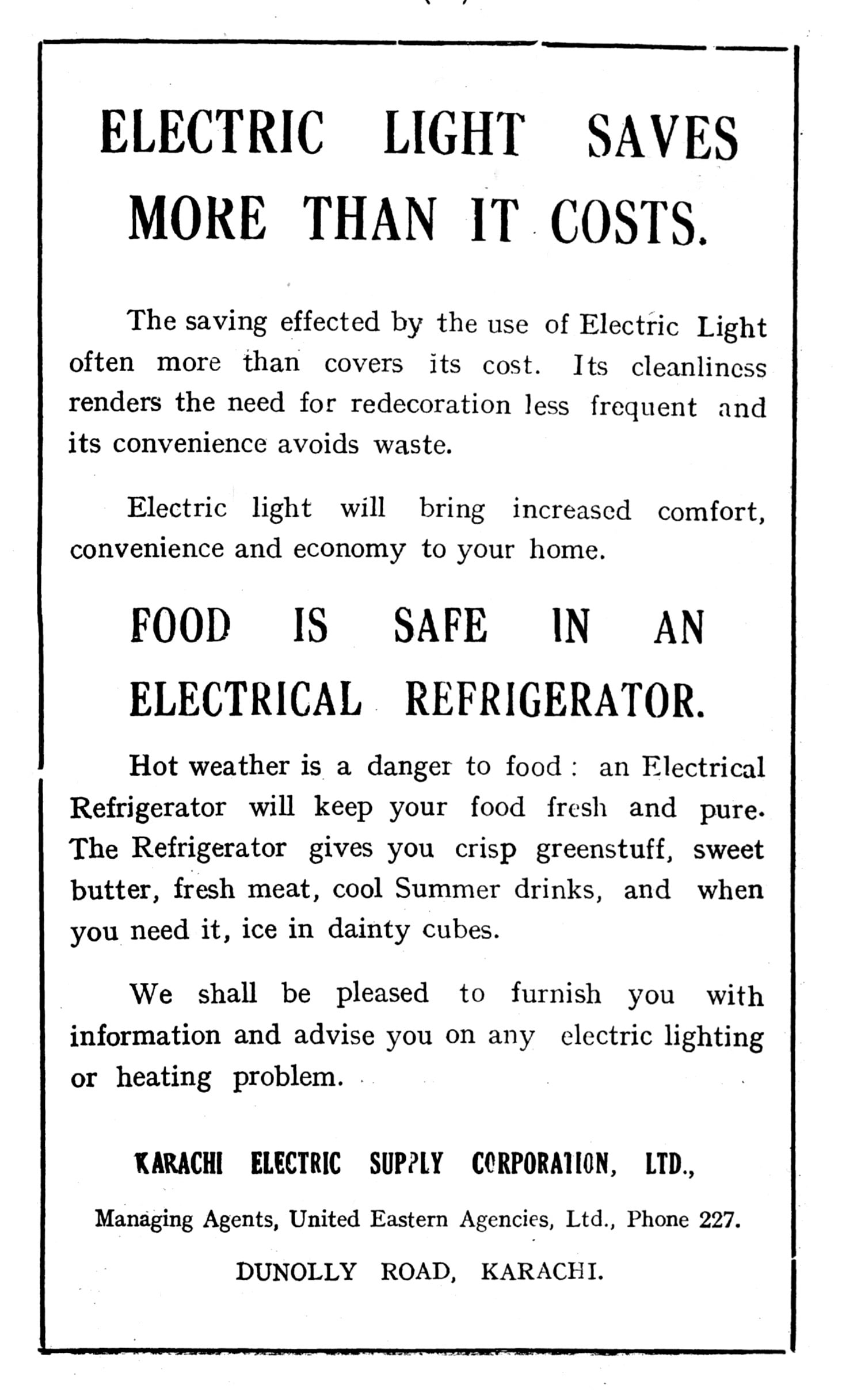

Throughout Pakistan’s tumultuous 70-year history, the advertising sector has undergone significant changes, reflecting changing global consumer patterns as well as the development and evolution of local trends. Indeed, as a developing economy poised at the intersection of South and Central Asia and the Middle East, Pakistan’s changing advertising landscape is a witness and an archive of changing mindsets and practices, as well as of wider socio-economic trends.

Throughout these changes, Pakistan’s oldest advertising medium – Pakistan’s print industry – has continued to maintain its position not only as the source of record for news and analysis, but as a medium of choice for advertisers seeking high-impact and high-visibility solutions.

In addition to changing consumers, Pakistan’s advertising landscape has been transformed by the introduction of new media. From 1947 to date, Pakistan has witnessed the growth of radio stations and outdoor advertising options, in addition to the mushrooming of private TV stations in the last 20 years, as well as the more recent explosion of digital advertising. Indeed, as internet penetration continues to grow, particularly on mobile devices, Pakistani consumers are now irrevocably linked to the wider world.

Throughout these tectonic shifts in the media industry, the ability among audiences to access content relevant to their interests (and increasingly on the go) continues to expand further, facilitating the flow of information and ideas.

Despite the introduction of new media for content delivery, Pakistan’s print media has continued to flourish, with advertisers placing their faith in a medium that will gain them visibility and deliver results. The resilience of print advertising can be attributed to three main factors. The lack of advertisement clutter versus other media, the higher attention and engagement rate of readers and the prestige and permanence attached to advertising in print versus other media.

As print publications focus on providing easy-to-read designs centred on providing readers an engaging reading experience, newspapers and magazines are increasingly limiting the quantum of advertising per page, focusing their efforts on delivering high-quality content and maximising the visibility of insertions.

Indeed, the clutter in advertising in other media further enhances the effectiveness of print advertising – while TV commercials or radio spots may be aired a few times, their impact is limited to those moments during which they are aired. As a result, print emerges as the place of record for advertisers to announce new products or lines, driven by the permanence of a print insertion.

A large part of the resilience of print advertising can also be attributed to the dynamics of print readers compared to radio or TV audiences, because print remains (in a world increasingly focused on multi-tasking) a high-engagement medium, requiring the full attention of readers compared to more passive media. For advertisers, print advertising thus provides an opportunity to reach consumers while they give their undivided attention and focus.

As Pakistani consumers have evolved over the last 70 years, the advertising industry has kept pace, providing brands with new and innovative opportunities to target consumers. Throughout all this, with the introduction and mass availability of TV (initially restricted to a few terrestrial channels but now expanding to a multitude of cable channels) as well as the growth of digital advertising options, Pakistan’s oldest advertising medium continues to flourish.

Leveraging the hallowed relationship between readers and their morning newspaper, print continues to provide advertisers across Pakistan the opportunity to reach out and leave an impact on an engaged and loyal readership.

Ali Hasan Naqvi is Senior General Manager Marketing, Dawn.

BREAKING THE DIGITAL CONUNDRUM

Unless digital publishers in Pakistan are prepared for a comprehensive rethink, they are unlikely to ever achieve a sustainable revenue model, writes Jahanzaib Haque.

As we enter 2018, consensus has largely been reached that digital in its many evolving forms, is the future of publishing. One individual stubbornly continues to disagree though – the accountant. Her lament is built on a point that should have everyone concerned; publishing on the internet is nowhere close to generating the kind of revenue seen in print, and compared to TV, it is a mere blip.

Unfortunately, even card-carrying digital advocates such as myself cannot call this a short-term problem that will resolve itself as digital continues to grow. There are many challenges, some of which will take years to overcome, and some that may never be resolved. Disclosure: in my role as Chief Digital Strategist at Dawn, I am involved in online marketing/sales and oversee the sponsored content desk.

Earning at scale. Let’s start by taking a look at the numbers drawn from the annual Aurora Fact File. Of total ad spend in FY 2016-17, print accounted for 23% (Rs 20 billion) and digital for six percent (Rs 5.5 billion). Print ad revenue increased by 11% compared to last year and digital increased by 22%. Even if digital were to continue growing at this rate, it would be years before it would earn half as much as print.

It can be argued that in the long-term, digital will catch up and pass print earnings but until such a time, the mantra of digital being able to ‘save’ print is mostly myth. If anything, print revenue will have to shore up digital operations for some time. Facebook, YouTube, Netflix, Snapchat and other giants are now putting all their weight behind video and making a comparison with TV necessary. To keep it brief, total ad spend on TV in FY 2016-17 was Rs 42 billion – digital will simply not be challenging that.

Frenemies. Then there is the Google/Facebook duopoly to contend with. For publishers, both are a blessing, extending reach, engaging audiences old and new, increasing traffic to sites etc. On the earnings front, not so much.

The two companies earn a majority of global spend on digital advertising, to the extent that a recent forecast by GroupM sees the two attracting 84% of all ad spend next year, excluding China. This is almost exactly in line with the Pakistan market, where the combined revenue of Google and Facebook accounted for 83% of total ad spend in FY 2016-17.

There is little chance for publishers to grab a bigger slice of the pie, especially when it comes to banner ads. Inevitably, programmatic advertising (which both Facebook and Google excel in) will negatively impact anyone involved in the business of creating, procuring and running banner ad campaigns, possibly to the point of redundancy. The problem is further exacerbated by the growing trend of users installing ad blockers for banner ads.

SMH B/C #FAIL (Shaking my head because #fail). This brings us to the next great challenge – one that applies to everyone operating in the digital sphere, not just the publishers. To put it bluntly, brands, ad agencies and marketing teams appear to be sailing rudderless, both on the strategic and creative front.

This has given us banner ads with tiny fonts and over 20 words of text; tired, old press releases labelled ‘sponsored content’; 30-second long online video ads that are copy-pasted TV commercials; absurd tenancy requests for ad space; far more absurd requests for permanent access to a publisher’s real-time analytics; paid content published on the worst possible day of the week because offline deadlines matter more than traction; social media posts that require $2,000 of boosting to secure 200 comments because that is the KPI; laughably bad Facebook videos/Insta stories/Snapchat updates posing as content, with the brand integrated with the subtlety of a sledgehammer; requests to run full TVCs on Facebook pages, buying bloggers (and journalists) to shamelessly plug products/services and my personal favourite – paying double to publish a press release because it’s the end of the year and budgets must be spent.

The situation is grim. Brands are allocating more and more to digital spend every year and publishers are pumping money into their digital operations, irrespective of the bottom line. But if 83% of revenue is going to Facebook/Google and the rest is being put into churning out subpar campaigns that audiences are bored by, blind to or block, there is need for a big rethink.

Some of the above challenges admittedly have no clear solution. Those require acceptance, adaptation and more importantly, inclusion when making decisions. For those problems that can be tackled however, a lot can be done, and done fast.

After all, we are blessed with not having to invent or reinvent anything; global trends, strategies, creative ideas and solutions are just one Google search away. It is only the will to change how we conduct business that appears to be lacking.

Jahanzaib Haque is Chief Digital Strategist and Editor, Dawn.com.

BILLBOARDS IN THE STARRING ROLE

Not long ago, OOH was viewed only as a support medium; today, it has moved centre stage in media planning. Ahsan Sheikh examines this great switch.

OOH advertising is one of the oldest mediums, globally, as well as in Pakistan. In Pakistan, we can divide its evolution into three eras: hand-painted signage (1947-1990), large format spectaculars (1990-2010) and outdoor to out of home (2010-present).

Hand-painted signage

(1947-1990)

Lahore’s film industry contributed immensely to the development of hand-painted boards – and some of us may still remember the large format Maula Jatt (Sultan Rahi) and Anjuman portraits painted on cinema façades and their impact in drawing in the crowds.

Initially, only a limited number of brands leveraged the medium. Hand-painted boards were found at railway stations promoting electric fans, beauty creams, tobacco and tea. From the seventies onwards, there was a spurt in the usage of the medium.

Large format spectaculars

(1990-2010)

OOH was given a boost with the advent of large format spectaculars and digital printing in the nineties; companies such as Coca-Cola, Nestlé, Pakistan Tobacco Company and Unilever were among the first to invest in these new formats that provided both scale and impact.

All the top brands soon followed suit. Along with this, came a shift in pricing. The earlier hand-painted boards cost only a few thousand rupees annually; now prices went into hundreds of thousands per month. Despite this, huge structures started proliferating across the major three cities and city municipal authorities started to impose taxes on them, which were then used to develop the city landscape.

In this respect, Lahore owes a lot to the outdoor industry, given that the city’s horticulture landscape was mainly funded by taxes collected from the outdoor media. So aggressively did the authorities collect funds in exchange for permission to erect billboards that an unprecedented number of structures went up between 2000 and 2010, especially in Lahore. Inevitably, clutter began to compromise the effectiveness of the medium and in 2008, the Punjab Government took measures to rationalise the installation of outdoor structures.

All billboards in Lahore were removed by the Parks and Horticulture Authority (PHA) and bylaws were enacted to prevent their installation. This was a blessing in disguise as the reduction in the clutter enhanced the effectiveness of the medium, and brands started reassessing OOH with renewed interest, leading to a demand for further innovation, such as backlit billboards and large cut-outs.

With new options coming on stream, the need for specialised planning and execution agencies arose and the concept of outdoor media agencies (OMA) started taking hold – pioneered by Unilever with the appointment of Adservice, and Nestlé with the appointment of Adkings.

Outdoor to OOH

(2010-present)

Until 2010, outdoor was considered to be a support medium to TV and print. The artworks were a basic adaptation of print ads, with little thought going into the effectiveness of the communication.

Then, another major shift took place when international specialist agency brands, such as Kinetic, entered the picture and outdoors started evolving into OOH. This included the activation of new touch-points in the OOH space within retail spaces and on-ground.

Clients started focusing on rationalising their OOH media planning in terms of target audience, with increasing focus on the quality of the execution. Monitoring and tracking (once a huge transparency challenge) became a standard service offered by all OMAs.

Today, tools are available to evaluate campaign coverage, assess creative impact, select sites according to specific target audiences and monitor and track results. In 2015, the Pakistan Advertisers Society (PAS) appointed Measuring OOH Visibility and Exposure (MOVE) to conduct OOH measurement and despite the slow traction it has received, this development did provide a number of criteria (reach, frequency, Gross Rating Points [GRPs] and Cost Per Rating Point [CPRP]) for the selection of OOH, based on the target audiences of each brand (rather than selecting the sites most likely to be seen by the brand manager and the marketing directors).

Today, with more capability and professionalism coming into OOH, brands are engaging OMA’s at the strategic level. This is a paradigm shift, given that not until too long ago, OOH was viewed as a support medium and has now moved to the centre of the overall media planning effort.

The factors contributing to this development are changing consumer behaviour patterns (not least the fact that they are spending more time out of home). There was a time, when during the airing of popular TV dramas, the roads would be relatively empty with people glued to their TV sets. Today, there is no TV show that audiences need to stay at home to watch live; they can watch it on their smartphones or watch the repeat the following day.

In fact, consumers are spending 70% of their waking life out of home and finding their entertainment on the go. Another benefit of OOH for advertisers is that it cannot be turned off, blocked or skipped and unlike TV and online advertising, it cannot be so easily avoided. OOH and mobile are becoming increasingly interlinked and more and more brands are leveraging both media.

We will remember 2017 as the year OOH started going digital in Pakistan and digital, once introduced, expands rapidly. In the UK, digital inventories increased from 6,181 to 17,356 (almost 300% increase) in two years between 2014 and 2016 and is expected to cross 50,000 units in 2021 (source: Outsmart / Kinetic).

In Pakistan’s case, the important factor will be how effectively all stakeholders leverage digital in terms of creative execution, effectiveness and placement.

Article excerpted from ‘From support medium to starring role’, published in the November-December 2017 edition of Aurora.

Ahsan Sheikh is CEO, Kinetic Pakistan.

BERGER PAINTS: YOUR CASTLE’S BEST FRIEND

Berger Paints have been in Pakistan for 70 years. Their branding has gone from a basic to a stylised representation of the modern homemaker’s dream. The theme has always been the product benefit. It is the way this is communicated that has changed.

In the fifties, there was something innocent about Berger’s ads. Focused on the benefits of using the paint, there is naiveté in the messaging. It is simple and straightforward; there is no spin. An explanation of what the paint does, with simple illustrations delivers the point.

The sixties saw the introduction of the ‘Robbialac Look’. It was about having a freshly-painted look throughout the year and the availability of a wide range of colours. The illustrations became better, the copy got a bit creative. In the seventies, the illustrations were replaced by photographs. The headline stated the problem, and the body copy gave the solution.

Every ad illustrated a new USP – appealing to the rational mind of the consumer rather than the emotional side. In the eighties, graphics were introduced. The message was that Berger was a global brand offering high-quality paint. The nineties focused on health. Lead-free paints were introduced and the copy emphasised benefits of these paints. The brand was evolving but not connecting. Human emotion was missing.

This has changed. Berger now engages with young homemakers for whom paint is as important as their furniture. Berger took a huge leap by focusing on a younger target group. A celebrity endorsement has been introduced with Mehwish Hayat, because celebrities inspire people to be like them.

From a rational, somewhat distant brand, Berger has evolved into an emotional, connected and iconic brand. From selling paints to selling lifestyles, the brand has left a footprint in every household.

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

Social media has drastically changed what consumers expect from brands. Urooj Hussain examines what brands must do to adapt to this altered demand.

Social media has changed the way we view the world. The evolution has been exponential; for example, in Pakistan, Facebook has gone from 11 million active users to 34 million in the past four years alone. The way people use social media has also evolved. Nowadays, they don’t go online to connect with family and friends; they go there to express themselves about anything and everything. It has also changed the way we view and interact with the world and the communities around us, and it has changed the way consumers behave online.

Audiences are less concerned with privacy. Since Facebook is free, many people do not necessarily realise that they are the product. ‘Likes’ and ‘comments’ are the currency that most Millennials and Gen Z thrive on and so, they give away vast amounts of personal data publicly to gain popularity on social media. The Pew Research Centre for internet and technology finds most young people more than willing to hand over their personal details. Ninety-one percent post photos of themselves, 71% post the city or town where they live, more than half give their email addresses and a fifth, their phone numbers. This gives advertisers a great deal of leverage in terms of data-backed targeting, which they never had before.

Brands need to adopt causes and give a collective voice to their consumers. It was the Arab Spring that gave traction to the idea that anyone can bring about a revolution on social media. Consumers know how powerful a social media platform can be and are willing to use it, be it for political issues or consumer complaints. As a result, brands need to tread carefully on social media as a single piece of negative news can snowball into a business damaging situation.

Consumers are more likely to trust a brand with a social media presence. According to a Forbes consumer study, 82% of consumers are more likely to trust a company with a digital media presence. It adds to the transparency, two-way communication, engagement and in some cases, social responsibility as well.

What is the effect of all of this on how brands advertise on social media? Pakistani brands have become savvy. They have come a long way from acquiring ‘likes’ on Facebook and realise that simply posting on their social pages will not do anything to give them traction online. High levels of clutter and increasingly distracted audiences means that brands need to invest in breaking through the barrier of limited organic reach and create engaging content.

Here are some examples of how brands are using social media to its full potential:

E-Commerce. E-Commerce has grown in an extremely interesting way on social media. Not only has it benefitted large-scale online retailers such as Daraz and Goto.pk, which use the platform to drive large numbers of traffic to their websites, it has helped a huge number of small businesses reach out to their customers with as little as Rs 100 per post promotion.

Influencer Marketing. The ‘democratisation of stardom’ is what this phenomenon is being called globally. Micro-influencers and vloggers have become huge social media celebrities without ever having been on the big screen. They have grown via popular demand on social media and are people which audiences can relate to. As a result, a lot of brands have signed on social media celebs such as Zaid Ali T and Ali Gur Pir to be their brand ambassadors, leveraging not only their popularity, but their individual social media profile to secure incremental and relevant reach.

Customer Service. In a world where customers want instant gratification, social media provides a platform where the consumer can connect to brands whenever they want. Being always-on and ready to answer consumer queries goes a long way towards building brand credibility. Facebook has made this process transparent by making public the ‘response time’ badges on brand pages, so that customers know the approximate time by when their queries will be answered. This is now considered to be an important KPI for social media management. Brands like Careem and KE have added to their credibility by actively responding to messages.

Social media and the way consumers use the platform will keep evolving at a rapid pace. Media experts need to be ahead of the curve and leverage new trends to their maximum potential.

Urooj Hussain is Associate Director Digital, Brainchild Communications. She can be contacted at urooj.hussain@starcompakistan.com

IN SEARCH OF CUPID ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Elhaam Shaikh on how Dawn Films are digitally promoting Saat Din Mohabat In.

In today’s age of information overload, the challenge every venture faces is how to break through the clutter to communicate effectively and inspire action. As a result, promotion of films now heavily relies on social media as they can garner huge amounts of buzz through word-of-mouth.

Films are content gold mines; the challenge is to build anticipation within a short period of time. Luckily, films are stories and stories sell, especially when you involve the audience in the story via social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat.

Dawn Films used these platforms in their marketing strategy for their forthcoming film Saat Din Mohabat In, leveraging viral marketing by doing something that would create talkability. The first introduction to the film’s content was to present the audience with the protagonist, who is searching for the love of his life and whom he must find in seven days.

He turns to the audience for help to go about this in the best possible way. His earnest request garnered an equally sincere response from some of the industry’s big stars, as they gave advice on the right way to go about his quest for love.

Numerous blogs and digital content powerhouses picked up on the subject matter, which in turn fuelled interest, adding to the conversation about the young man’s quest. Added to this, glimpses of the romance, drama, humour and action contained in the film gave audiences a peek into the unfolding storyline.

Drumming up interest and seeding your trailer online is always a challenge, but the marketing effort for the film, bridged the gap by offering a storyline and enabling fans to respond, thus generating a buzz. The stage was set and audiences were drawn in with content such as clips, articles, conversations, GIFs and behind-the-scenes shots of the protagonist’s journey, leaving a taste of what is to come.

This is the tip of the iceberg. Stay tuned to your digital screens for more creative content as we weave in and out of the story, taking fans along for the journey.

Elhaam Shaikh is Manager Programming, CityFM89.

AN ENCOUNTER WITH ‘ADVERTISING’S THIRD BILLION’

Ayesha Shaikh explores the opportunities and challenges for women pursuing an advertising career in the age of the millennial.

The period television drama Mad Men set in the high-pressure advertising world of New York during the sixties, was not that far off in projecting the advertising industry as an all boy’s club. Just as Peggy Olsen’s progression from a secretary to a copywriter in the show was fraught with struggles to prove her creative talent and capability before she was taken seriously, women who enter the advertising profession have never had it easy.

When I started working on this story, I was certain that the premise of the article would be that Pakistan’s advertising industry is non-inclusive of women. As I began speaking to women working in advertising agencies, from different disciplines and age groups, to determine if the ad industry in Pakistan is female-friendly, it became evident that my initial perception was erroneous.

There was general consensus on two points. First, the number of men who have reached the highest echelons of power in media and advertising is far greater than the women who have smashed the glass ceiling, despite the increasing number of women who have assumed leadership roles. Second, the industry is far more female inclusive than anywhere else in the world.

According to Rashna Abdi, Chief Creative Officer, IAL Saatchi & Saatchi, “late sittings are unavoidable at times but that is how the industry works across the world. The advantage is that in Pakistan, if women stay after hours, transportation is usually provided, at least at IAL.”

Abdi’s comment points towards an underlying problem voiced by industry veterans as well as newbies: a lack of structure, benchmarks and standardised policies. This is mainly attributed to the fact that there is no governing body which regulates agency operations.

It is this vacuum that has resulted in variable HR and operational frameworks, since agencies in Pakistan are not required to comply with a designated set of rules in managing their workforce. Agencies therefore, have carte blanche in formulating their HR handbooks. At one end of the spectrum are agencies such as IAL Saatchi & Saatchi that provide transportation and other benefits to ensure a women-inclusive culture, at the other end, are a host of organisations that choose not to, without any fear of consequences.

The two most significant issues that this lack of standardisation has created concern gender-based wage gap and maternity leave. Tannaz Minwalla, GM & Creative Director, Creative Unit, says, “when I started my career as a visualiser at IAL in 1982, and later as the head honcho when Creative Unit was established in 1987, I had to fight for equal pay.” She adds that people objected to women being paid as much as men on the grounds that “they have no dependents or financial commitments and are far more likely to leave when they marry or start a family.”

The issue of disparity in compensation goes well beyond Pakistan and its advertising industry. According to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) report 2016, women across the world earn 23% less on average compared to their male counterparts working at the same hierarchical level.

Since Pakistan is typically late in adopting and complying with international best practices, it was almost a given that the ad women to whom the question of compensation inequities would be posed would reaffirm Minwalla’s views.

As surprising as it was to learn from Abdi that our ad industry is actually ahead of the curve in terms of creating a female-friendly work environment, it was even more startling to hear Atiya Zaidi, Executive Creative Director North, Synergy Dentsu, say “gender-based wage gap is just a perception. I am proud to say that I am a woman working in Pakistan’s ad industry, earning as much as my male colleagues at the same level.”

Zaidi’s opinion is seconded by Abdi, who believes that the industry is moving towards parity in compensation for both genders. To a large extent, this shift has been triggered by the increasing number of women who have forayed into media and advertising since the nineties, predominantly on the creative side. There was a gradual recognition of the value of their contributions to creative and strategic processes.

This in turn changed the perception of women from being ‘HR liabilities’ to a source of competitive advantage for agencies. As women continued to progress quickly through the ranks, their influence in decision-making increased, as did the salaries they commanded.

Zohra Yusuf, Chief Creative Officer, Spectrum Y&R, has a different take as to why women’s pay scales have been on the rise, attributing it to a strategic change in the way the industry operates. She recalls that when she joined MNJ in 1971 as a copywriter, it was the male-dominated client services department that enjoyed better incentives, including higher pay scales.

This is because at that time, the majority of accounts were won on the basis of personal relations with clients rather than the big idea and therefore, client services executives were considered the most valuable resource. In the last decade or so, as the focus shifted to creative conceptualisation and execution, it is the women-dominated creative departments that have taken centre stage. According to Yusuf, this is the main reason why there has been an across-the-board increase in compensation levels for women.

Abdi adds that Millennials have played a significant role in changing the perception of advertising as a profession. “Compared to previous generations, young people have a very different outlook and they do not see advertising as an inappropriate profession for women. There are a lot of young women who study commercial and communication art and then opt for advertising because they believe it provides opportunities for independent, creative expression.”

There is no question that the working conditions for women in advertising have improved considerably. However, the ad industry still has a long way to go before they can claim gender parity and inclusion in the truest sense.

Nida Haider, Managing Partner and Brand Strategy Director, IAL Saatchi & Saatchi, highlighted one of the most pressing issues affecting organisations across the world; the increasing dropout rate of women from the workforce after marriage.

In her view, “unless the concepts of maternity leave and flexi-hours are not incorporated into HR policies, working mums will find it difficult to resume their careers, particularly if family support systems are not there to lend a helping hand with children.”

While Yusuf concurs that greater flexibility is needed if agencies want to retain valuable, talented and dedicated female employees after they start a family, she points out that it is not financially feasible for advertising agencies to mirror the benefits offered by multinationals.

“Agencies do not even come close to generating the kind of business volume and revenues that large corporations do. Providing on site child care and paid maternity leave are substantial financial commitments that agencies, particularly smaller ones, will not be able to sustain.”

To conclude, it is an undeniable fact that despite the odds, women in the advertising industry have made significant strides by relying on their creativity, talent and grit. While gender diversity in leadership roles and parity in compensation are important wins, there is a long way to go before our advertising industry can claim being an equal opportunity employer for men and women.

Ayesha Shaikh is a leading advertising and communications expert at Aurora. She can be contacted at aurora@dawn.com

PAKOLA: ENGAGING WITH PAKISTAN’S MIGHTY HEARTS

Pakola was launched on August 14, 1950 and instantly became Pakistan’s favourite drink. How could it not? Here was a drink with a formulation that made it green!

Mehran Bottlers have a strong vision for Pakola; they understand the love Pakistanis have for the brand. Pakola has become the essence of what defines Pakistan. The satisfying taste drives the loyalty of consumers at home while for Pakistanis abroad, Pakola evokes intense nostalgia whenever they see the brand.

Pakola’s vision is to provide our consumers the world over with a variety of premium quality beverages that guarantee satisfaction while refreshing the national spirit. These efforts are indicative of the brand’s progressive attitude and a determination to continue the journey of being the drink of the people of Pakistan. In recent years, Pakola has revamped itself in order to appeal to younger audiences, both in terms of the message and the look.

A recent example of Pakola’s new approach to create brand love was our 70th Independence Day campaign, where we launched limited edition Pakola cans along with a social media campaign ‘#PakolaAurPakistan’ and ‘#70thBirthday’. The cans paid tribute to the Quaid-i-Azam, while Pakistan’s flag and truck art motifs were incorporated on the cans, thereby emphasising the brand as being the drink of Pakistan. This resulted in people posting photographs on social media and creating a buzz online.

Pakola is a brand that evokes pride, love and patriotism. Pakola connects our hearts and minds with the national spirit. After all: ‘Dil Bola Pakola!’

THE 21st CENTURY: WHEN CONSUMERS AWAKE

REVVING UP RETAIL

Ayesha Shaikh explores a new diversification in consumer preferences and factors fuelling an exponential growth of retail in Pakistan.

There was a time when every neighbourhood had its kiryana store. Families had fixed monthly grocery lists that were handed over to the shopkeeper, who would put all the items together, bag them and hand over a chit with the billed amount scribbled on it. Apart from the haggling (it was expected), the next customer decision was whether to pay in cash or put the amount on a monthly tab and whether or not to have the groceries delivered.

Product choices were limited and the purpose of the ‘shopping’ was to ensure enough rice, flour, sugar, salt, cooking oil, banaspati ghee, masalas and spices to last the month.

In those days, Naheed and Imtiaz in Bahadurabad and Agha’s, Motta’s and Paradise in Clifton, were among the few retail outlets where customers had the luxury to browse shelves stocked with limited varieties of imported brands and/or local packaged goods. Other than those, shopping excursions were limited to Juma bazaars or visits to Laloo Khait (now Liaquatabad), Empress Market or Jodia Bazaar – the wholesale hubs of Karachi.

It was only in the noughties, when due to increased exposure, Pakistani consumers became more aware of what was happening internationally and a significant shift in lifestyles and buying patterns started taking place.

Varied product assortments, greater convenience and accessibility, better merchandising, improved service and an enhanced store experience became the new retail rules. Quick to recognise this shift, local retailers began to invest in improving store layouts and their product mix.

There was renewed focus on customer service, rather than relying on price competitiveness. As a result, this growing retail potential put Pakistan on the radar of global retailers.

A new dynamic

According to a study conducted by Standard Chartered Bank last year, between 2011 and 2015, the size of the retail pie in Pakistan jumped from $96 to $133 billion, a 38.5% increase.

The current value of Pakistan’s retail sector is estimated at $152 billion, as per Planet Retail (a global retail consultancy). It is the third largest contributor to the economy (after agriculture and industry), accounts for 18% of the total GDP and is the second largest employer (after agriculture) providing jobs to more than 16% of the total labour force. (NB: As most of retail in Pakistan is unorganised, therefore undocumented, industry analysts agree that the on-ground figures are much higher).

With an annual growth of eight percent, retail sales are expected to cross the $200 million mark by the end of 2018. The main factor fuelling this, apart from increasing urbanisation, is an improving employment-to-population ratio which has led to higher disposable incomes, thereby expanding the middle class and increasing consumer spending manifold (estimated at $293 million in 2017 and projected to cross $333 million by 2018).

The other trend disrupting traditional retail is e-commerce. Although still at a nascent stage, internet retail is expected to become a significant complement to brick-and-mortar grocery and non-grocery retailing in the coming years.

The morphing of ‘mall’ culture

Dolmen Centre in Tariq Road (established in the nineties), was the first vertical shopping complex in Pakistan built on a multiple floor layout. Before that the concept of indoor air-conditioned shopping areas was alien in Pakistan. If people wanted branded products, Zainab Market or Panorama and Rex Centres were the go-to places.

However, the mall did not turn out the way it had been envisioned. There were not enough local brands because many did not want to assume the high rents Dolmen Centre demanded. It was almost a decade later that Pakistan had its first shopping mall, when Park Towers opened in Karachi.

The mall morphed into a social venue, where people went to enjoy the amenities rather than to buy. The opening of Dolmen Mall Tariq Road in 2002 proved to be a game changer. Dolmen Group’s prior experience had taught them that the only way to convince the big names to come onboard as tenants was to ensure customer traffic.

The two strategic decisions that paid off were the establishment of Sindbad’s Wonderland and a food court. Positioned as a family recreational spot, the mall began to bustle with activity convincing retailers to invest in space. Over the next 15 years, a number of malls were established (mostly in Karachi), redefining the shopping experience. The entry of Hyperstar in 2012 (operated by the Carrefour retail chain) as an anchor tenant at Dolmen Mall Clifton was another game changer.

Hyperstar became a retail success, prompting other mall operators to adopt the idea of having anchor tenants. North Pakistan is now at the forefront of the retail race and several multipurpose malls are under construction in Bahawalpur, Faisalabad, Gujranwala, Islamabad, Lahore, Multan and Rawalpindi.

A facelift for grocery shopping

This shift in consumer shopping preferences, from a ‘product-price focus’ to an ‘assortment-experience’ focus, did not go unnoticed by local grocery retailers, such as Naheed and Imtiaz supermarkets, which underwent a 360-degree remodelling and transformation after 2008, by adopting a multi-level department store format.

Both supermarkets began as small kiryana shops in Bahadurabad. While Imtiaz’s strength remained budget grocery offerings, such as flour and masalas, Naheed differentiated itself by introducing imported brands.

Naheed expanded its footprint from the original 1,100 square feet of retail space to a 32,000 square feet, four-level departmental setup. Imtiaz followed and established outlets in DHA, Gulshan-e-Iqbal and Nazimabad, three of the most densely populated neighbourhoods in Karachi.

A roadmap for retail

Macroeconomic indicators point to a sustained boom in Pakistan’s retail industry and modern grocery retail market represents a key area of expansion. Increased competition is likely to further boost the sector and the entry of foreign players will force local retail giants to rethink, revamp and remodel their businesses.

A second area of opportunity is projected to be in the ‘mall culture’, particularly in the northern part of the country, as well as in second-tier cities where there is a demand-supply gap. A policy initiative increasingly asked for by the stakeholders is the establishment of a national retail association that can represent the sector’s interests, negotiate with the government over tax reform and introduce consumer protection laws. Abbasi sums up the future of retail in Pakistan: “One thing that will not change is that people will continue to shop; what will change is what, where and how they shop. For retailers who are able to read the market pulse and predict future buying trends, the sky is the limit.”

Article excerpted from ‘Retail revs up’, published in the May-June 2017 edition of Aurora.

Ayesha Shaikh is a leading advertising and communications expert at Aurora. She can be contacted at aurora@dawn.com

ENTER THE CONSCIENTIOUS CONSUMER

Marylou Andrew on how technology has forged a new consumer activism.

As consumers of brands, we have come a long way in the last 30 to 40 odd years. Gone are the days when we accepted advertising at its word, didn’t read brand labels and assumed that big (and small) businesses always functioned in moral and ethical ways. We now live in the age of the ‘better informed, more sceptical and less likely to take bullshit from brands’ consumer. And just how did we get here? In a word: technology.

Before the advent of the internet and social media in particular, access to unbiased opinions from consumers wasn’t nearly as easy, despite living in an increasingly globalised world. News travelled slowly, people had less access to information and most importantly, only a handful of people – be it politicians, lobbyists, journalists or brand managers – controlled (and often censored) the narrative that was fed to the public.

Until the fifties, phrases like ‘doctors recommend’ were commonplace in tobacco advertising and even as late as the eighties and nineties, smoking was considered cool remember, ‘Come For The Style, You’ll Stay For The Taste’ type ads; the unethical practices of companies like Monsanto, among others, were hidden from the public eye and consumers put their confidence in advertising that sounded good but lacked authenticity (Dove, I’m looking at you).

Fast forward to the present, where my favourite columnist, Nicholas Kristof, in a recent article wrote: “Millennials want to work for ethical companies, patronise brands that make them feel good and invest in socially responsible companies... doing good is no longer a matter of writing a few checks [cheques] at the end of the year, as it was for my generation; for many young people, it’s an ethos that governs where they work, shop and invest.” (New York Times, January 24, 2018)

Driven by an unprecedented access to information and opinion, younger consumers ‘care’ about who stitches the clothes they wear (big fashion with third world sweatshops beware), who makes the movies they watch (no more Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby please) and whether their food is safe and healthy (think crackdowns on MSG, hormone and antibiotic pumped dairy).

But while this concern can occasionally – although not always – be shallow in that it doesn’t always translate into action (some of us still shop at Zara right?), what is unwavering is the trust that consumers place in the words and opinions of others, over that of brand messaging. To put it another way, unbiased peer reviews trump advertising… Every Single Time.

While brands have accepted consumers’ rights and ability to express their opinion freely in a socially connected space, what has been harder to stomach is the fact that the consumer decision journey has changed almost entirely. People have always sought to gain value from their purchases and that remains the only constant.

What people perceive to be of value and how they obtain it, looks very different from what it did a decade ago. Although price and quality remain important, the brand’s ethos, the ethics of the company’s executives and most importantly, what other consumers think about the brand, are paramount to the expression of value.

What is interesting, and disconcerting, is that sometimes a brand that doesn’t necessarily have the best in class product or even offer the best value, can become a hero, based on how it is perceived and portrayed by ‘influential’ consumers.

This is the dark underbelly of the new consumer revolution, one in which consumers, because of their sheer reach and influence, have the power to destroy brands, and will sometimes use this influence maliciously while at other times, they may ‘sell’ themselves out to brands that seek to harm the competition.

Still, it is fair to say that more brands use consumer influence in positive rather than negative ways and converting social media influencers into brand advocates has proven to be a very effective strategy.

These brand advocates, as evidenced by hundreds of full disclosure statements on blogs and Facebook groups, are generally very concerned about transparency because they know that it is easier to lose followers over dishonest reviews than it is to gain them.

While there are many international examples to speak of, in the Pakistani sphere, there are two areas in particular where this strategy has worked exceptionally well for brands. The first is food (the industry in which I currently work) where influencer recommendation and/or criticism can pretty much make or break a business.

Consumers have become incredibly particular about what they eat, what goes into their food, and under what conditions it is manufactured. Going further up in the Maslowian order, ‘new’ and ‘exciting’ product offerings are embraced with great enthusiasm and the influencer who is able to cover the most launches and offer the best reviews, is most likely to have the greatest following. And it is natural that where consumers go, brands will follow.

Another area of growth in the realm of influencer marketing is women’s products and by this I mean fashion items, makeup, baby paraphernalia, books and anything else that a woman is likely to buy. Now this is pretty much the Holy Grail for Pakistani marketers because every product, with very few exceptions, is targeted towards the ‘housewife’.

Facebook groups like Soul Sisters Pakistan, Soul Bitches and a plethora of others have followers in the thousands and the word of the handful of women leading the group is considered gospel. As always, it is a time of challenge and opportunity for brands, but more pertinently, it is an incredibly exciting time to be a consumer of brands.

Marylou Andrew is Head of Product Excellence, Hobnob. She can be contacted at marylouandrew@gmail.com

LOST ON THE ACTIVATION HIGHWAY

Social media has provided activation a new lease of life. So why are activation agencies not taking advantage? Umair Kazi explains why.

Somewhere along the line, activation practitioners in Pakistan have lost their way. After the gloss of this ‘new and exciting’ marketing medium wore off, brands realised that they had to justify their spend on activation compared to their spend on ATL. This realisation brought into question the infamous ‘cost per contact’ metric that drives the activation landscape today.

Agencies responded by designing marketing activities, optimised to deliver the biggest bang for their buck in terms of cost per contacts. In all this hoopla, we collectively managed to critically wound, if not kill, the ‘experience’ part of experiential marketing.

Walk into any decent grocery store today and you will see this in action. In every aisle, there is a brand ambassador waiting to tell you about this and sell you that. In-store sales promotion is the official term of such activations, although ‘physical person-to-person spam’ would be more appropriate. The crème de la crème of activation channels, the mall, also saw a sharp decline in the engagement factor and potential ‘contacts’ had to be lured in with prizes and other incentives.

Most consumers, including myself, started avoiding activation campaigns like the plague. At the same time, social media took off and by 2014, most brands had become increasingly confident with the medium. They had gathered a sizable number of likes on their pages and needed content. This paved the way for a new addition to the activation brief; the social media angle.

Today, almost all clients want a social media element to their activation.

The evolution social+activation campaign

The social and experiential relationship has grown over the years in a number of ways. The first was simple captive integration. The idea is to create an activity that allows people to connect to their social media accounts and post stuff (ideally branded) about the activity and their part in it.

The problem with this approach is that it is restrictive, even with the help of customised software that can make the posting process smoother. In simple terms, participation is low because no matter how engaging the content is, it is a chore to post from a system you are not familiar with. For privacy nuts, it is an even bigger source of concern to enter sensitive login details from an untrustworthy location.

The second phase came with the advent of 3G and 4G technology. Now, people could do more than just check-in from their phones. This independence of social posting became a huge opportunity for the activation industry.

The formula for most activations was accordingly adjusted; custodians realised that if the activations were engaging, people would post about them, enabling a ‘multiplier effect’ online. The cost per contact was now being addressed by an online footprint as well, thereby unshackling it from strict activation targets. This helped brands refocus on creating a richer experience, even if it came at a higher cost and paved the way for visually engaging activations that encouraged people to whip out their phones, take a picture and post it.

The third stage came in the form of social-maximised campaigns. This is where an activity is executed on-ground with the sole purpose of acquiring word-of-mouth on social platforms. The idea is a limited experiential marketing campaign that targets only a handful of people on-ground, but is then fed online and spread from influencer to influencer.

This sort of experiential marketing is the rage internationally, but has only been exhibited a few times in Pakistan so far. A powerful example of this was recently executed by Olper’s. Rallying around their campaign concept that memories are made around the dinner table, they surprised couples dining in a restaurant by footing their bill.

Video content was created around their surprised expressions of joy, showcasing a range of emotions and even tiny interviews. The video was released on their social media properties. Although the number of contacts for the activity was minimal, the seeding of this on-ground campaign, along with its feel-good factor helped it spread fast and wide online.

A future with better experiences

As SoLoMo (Social Local Mobile) gains traction throughout the world, Pakistan is still playing catch-up. With a massive 140 million mobile phone userbase and a strong data liberation movement from our telecommunication operators, conditions are perfect for brands and agencies to move towards better integrated experiential campaigns that seamlessly harness the power of social.

An obstacle standing in the way is institutionalised thinking and a strong affection for the status quo. We need to take greater risks and encourage social to be a frontrunner instead of an add-on. The other big hurdle is disconnected campaign planning. The trust deficit between agencies working on different aspects of the campaign needs to be addressed and multiple partners need to work in tandem, not in silos.

The experiential marketing industry must quickly shape up and provide a pivotal and supportive role in this transformation. If we stay silent and limited to doing just ‘our bit’, we will become the ‘necessary nuisance’ that ATL has become and be chucked out in favour of a better online experience.

Article excerpted from ‘Activation agencies need to come up to speed or be left behind’, published in the July-August 2015 edition of Aurora.

Umair Kazi is Partner, Ishtehari. He can be contacted at umair@ishtehari.com

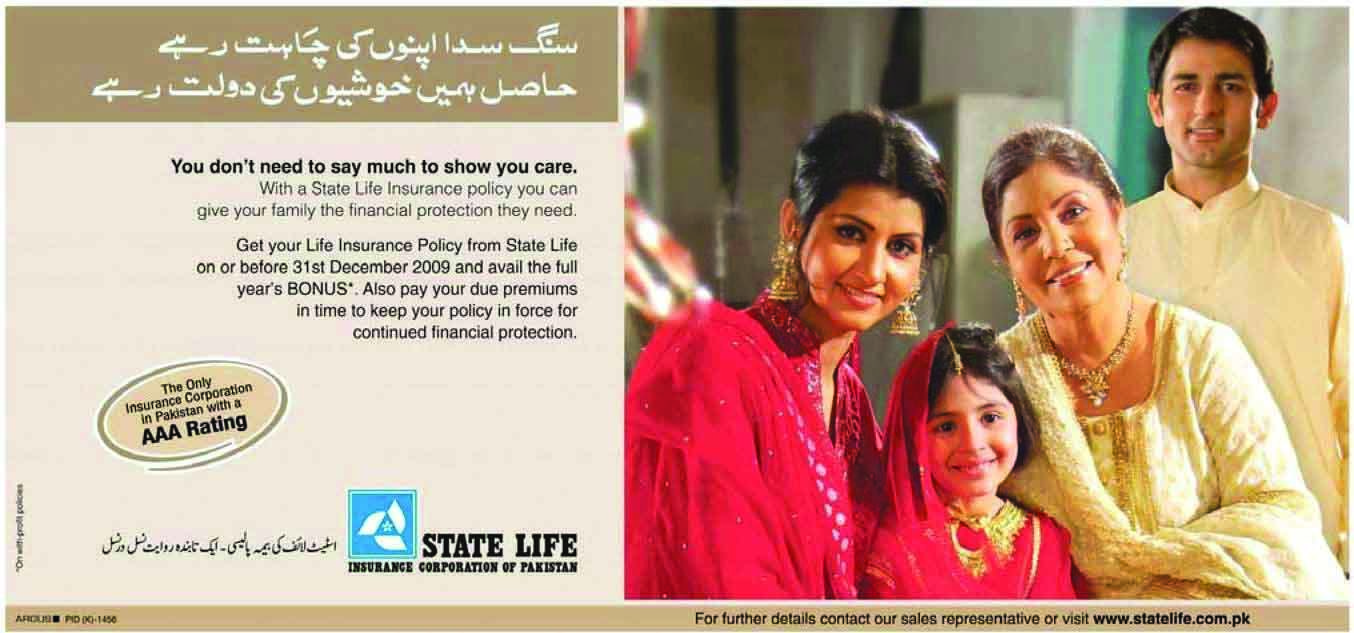

STATE LIFE: ENCOUNTERING STIFF COMPETITION

At the time of independence, there were only a few local insurance companies operating in Pakistan along with a few foreign companies; within 25 years, the number rose to 32. In 1972, under a Presidential Order, life insurance was nationalised in Pakistan.

This took place in two stages. Firstly, the management of the 32 life insurance companies was taken over by the government. Secondly, a single corporation called the State Life Insurance Corporation of Pakistan was established with three units called A, B and C. These three units are still incorporated in our logo in the form of three petals. The third unit, C, was in East Pakistan. In October 1975, the three units were merged and five zones were created (they are also part of the logo, between the three petals).

Initially, we advertised on radio and print, because the majority of our policy holders did not own a TV set then. The ‘Ae Khuda Mere Abbu’ campaign was developed in the 1980s, and showed a father-and-daughter situation; the emotional appeal of the little girl praying for her father’s life won people over and the TVC became an iconic ad.

We did a remake of the TVC in the 2000s, which showed the girl as a grown up, but it didn’t do well, because times had changed and so had the target market. Earlier, a father was the sole breadwinner; today, almost everyone in the family earns.

Furthermore, earlier, the perception was that life insurance is only of benefit after death, whereas today people can use the money they have invested over 20 years time. This was the idea we tried to communicate in our Eid TVC. Earlier, it was about a father who had to stay alive, now it is about a wise father who has invested in insurance for his children’s future. The branding of life insurance products has changed.

We have reduced our advertising on radio; our ad spend is equally divided between TV, print and digital.

Razia Dossa is Manager Corporate Communications, State Life Insurance Corporation Pakistan.

FROM CRUNCHING NUMBERS TO STORYTELLING SCENARIOS

To remain relevant to brand supremacy, market research companies need to rapidly effect a paradigm shift, writes Noaman Asar.

Within 20 years of Independence, economists were eyeing Pakistan as one of the fastest emerging economies; countries like South Korea were studying its model to replicate it. It was in this time of prosperity that Pakistan’s first market research company began operations.

Their first office was a humble setup on Tariq Road in Karachi in 1966. The proprietor of this innovative enterprise was Mahmoodul Hasan, a young graduate of the Institute of Business Administration (IBA). His tenet for the business was that there could be no compromise on the quality of data because clients would be making strategic business decisions based on this information.

The company thus ensured that the data collectors were well-trained, but it was also important to guarantee that the sample selection was scientifically done and representative of the universe under study and that the questionnaires were designed in a way to make sure they asked the right questions to get the right answers.

The people attracted to this field were comfortable with numbers and with inferring learnings by deploying statistical and mathematical tools. The pioneers were graduates from Ivy League universities, such as Dr Ijaz Shafi Gilani and Dr Javed Ghani.

Initially, clients were multinational companies,familiar with market research. In fact, companies like Unilever used to have a market research department as big as any research agency. This was the case up into the nineties, when Unilever, along with other multinationals moved away from this model and outsourced to specialist agencies.

This development led to the growth of the market research industry. Many local advertising agencies opened their doors and the industry saw a boom. It was around this time when mainframe computers were introduced, a development that saw a change in client expectations, as they then began to demand faster turnaround times and reports that would give them learnings rather than outputs.

In fact, clients expected their market research companies to have ‘marketing’ sense and this created the need for a new a mindset, whereby numbers were interpreted to generate insights. As technology gathered pace and new tools were introduced, clients wanted their research companies to be their partners rather than data providers. They were demanding insights with a clear direction on how to meet their business challenges.

Clients expected their market research companies to have ‘marketing’ sense and this created the need for a new a mindset, whereby numbers were interpreted to generate insights.

However, market research companies failed to step up to the plate and the emphasis remained on sharing data, with their output lacking focus, as the ‘data miners’ were mining sand rather than sieving for ‘diamonds’ (insights) and stories.

Market research companies require a paradigm shift. They need to transform themselves into marketing consultants. They need to understand the business, use the right design to test hypothesis and present findings that are relevant to their clients’ needs. Of course, market research practitioners need to be comfortable with numbers, but they also need the ability to create ideas that can break through the clutter. This transition is important in terms of how the future is shaping up.

It is expected that the market researcher’s job will be replaced by technologies and androids due to AI and machine learning. These machines will master what humans are good at by using their ‘left’ or their ‘rational’ brain. However, this does not mean that technology will replace humans. Humans will still be superior because of their ‘right brain’ or ‘emotions’ and will continue to interpret data and offer recommendations to grow brands based on insights and stories. Market researchers will have to become strategists and planners.

Noaman Asar is MD, Kantar Pakistan. He can be contacted at noaman.asar@kantar.com

THE THRILL OF INSTANT PURCHASE

Tariq Ziad Khan traces the resurgence of consumer finance and banking.

Any discussion about Pakistani banking tends to elicit divergent opinions. This is understandable because for an economy as undocumented as Pakistan’s, accurate numbers are hard to come by, even in an industry as heavily regulated as Pakistani banking.

Pakistan is unique in the sense of being one of the few countries that can boast of a number of banks that operate within its geographic boundaries for periods that predate its existence. As the young nation struggled to get off to a promising start, banks formed the core of the services industry and were key employers for the educated members of the workforce, which included a large number of refugees from India.

Pakistani banking grew as did the economic prospects of the country. An increase in multinational interests brought many mercantile banks from abroad, while many major business houses established locally-owned commercial banks.

However, this changed with the nationalisation of the major banks in 1974, as part of a larger economic reorientation in the country. While many people tend to remember nationalisation as the nadir of Pakistani banking (which it unfortunately did turn out to be), not many of them remember that it was part of a broader vision to provide banking to a larger segment of the population, as well as improve access to banking services in under-served and rural areas.

The fact is that post-privatisation, Pakistani banks had a readymade critical mass of low-cost deposits across the length and breadth of the country, as well as a branch network that served as an example of market potential, is forgotten.

Come the nineties and the post-martial law governments reoriented the economy to a more outward looking slant. Also, like Pakistani banking, Pakistani consumers changed too. The opening of the economy, along with the rise of satellite TV, the Gulf boom, mobile telephony and the arrival of the internet, significantly changed consumer preferences. Despite the ‘on again, off again’ recessive tendencies of the economy, increased competition among banks forced them to look beyond corporate and high net worth customers. This broadening of the target audience brought consumer banking in its true form to the Pakistani market.

The rise of consumer banking fed an almost insatiable urge among Pakistanis for brands in terms of automobiles (including Honda, Toyota and Suzuki), consumer durables and electronic appliances such as Haier, Orient, Pel, Super General and Waves. With the opening of the economy and the entry of foreign brands, banks capitalised on both, secured and unsecured lending with a ballooning portfolio of credit cards, personal loans, auto-financing and even mortgages.

Reporting for Aurora during those exciting times, I met a number of bankers across the three main segments of the industry. These were the large, formerly nationalised banks and subsequently dubbed the ‘Big Five’, multinational banks and locally-owned private banks (which were thriving by catering to middle-class customers). Being part of a marketing publication, my focus would be on optics of growth in the industry as well as the advertising that it produced.

Those were exciting times as for the first time, banks opted for high-cost productions, TVCs, cross branding, merchant alliances, brand partnerships and direct-to-consumer campaigns. Product development was in overdrive and products from other Asian economies were replicated at lightning speed, along with a drive for deposits and lending that mimicked a full-scale pricing war. Added to this, much work was undertaken in alternative delivery channels such as internet banking and ATMs (with the launch of two countrywide network switches).

My discussions with consumer bankers during that time had three broad themes: consumer banking was causing the overall growth in sectors such as travel, automobiles, home appliances and consumer electronics; the industry was extremely profitable (by some estimates, among the top five most profitable in the world), but subject to consolidation in the future resulting in fewer, albeit larger players; and although default rates were low (as low as 1.5%), this could change as borrowed assets aged or if the economy experienced another downturn.

Fifteen years and a stint working with two major banks later, I saw all these trends play out in different ways. Pakistan’s economy did once again see significant recessive tendencies during the post Musharraf/Great Global Recession period, and with major implications for consumer banking, particularly in terms of unsecured lending.

When I left Pakistan, the industry seemed to be on the cusp of a major consolidation and the focus had once again shifted to core banking products, particularly low-cost deposits, SME-secured lending and inward remittances. Banks had started parking more money in high-yield government securities.

Added to this, the increasing paid-up capital requirements and other regulatory tightening by the State Bank of Pakistan on marketing, coupled with limited legal recourse against defaulting customers, had made consumer banking outreach fairly limited for most banks.

Five years later, things are starting to change. With the maturing of a lot of those high-yield government securities, along with pressures on traditional banking revenue streams, it seems banks are now flush with cash and are once again willing to look at consumer banking as a way to augment revenue in the face of low discount rates.

With the mainstays of consumer banking (automobiles, electronics, travel and mortgages) again on the uptick, coupled with factors such as a consolidated banking sector with fewer players and the opportunities presented by CPEC, the fundamentals of the Pakistani economy show enough promise to keep banks interested.

One hopes that the best days of the industry still lie ahead.

Tariq Ziad Khan is a marketing professional who has worked with major brands in banking, advertising and the media in Pakistan. He is currently based in the US and can be contacted at tzk999@yahoo.com

AROUSING ASPIRATIONS

Durriya Kazi on the evolution of Pakistan’s most beloved and popular art form – truck art.

When Pakistan came into being in 1947, ways to identify institutions of a new country needed to be devised. Currency, postage stamps, passports, remembering to say Radio Pakistan rather than All India Radio and government stationery – all required attention.

Trucks used for transport of goods developed stencils for the three main companies. New Muluk (New Country), Sitara-e-Hilal (Crescent and Star) and Taj Mahal. Some tentative painted decoration crept in when Haji Hussain, a palace decorator from Kutch Bujh settled in Karachi. In the economic boom of the sixties, the fortunes of transporters grew as industries in Karachi needed raw materials from all over Pakistan.

The pride of the new transporters was mirrored in the emergence of excessive decoration that has become the hallmark of Pakistani trucks. When in 1963, Gohar Ayub acquired the monopoly to exclusively import Bedford trucks, it inadvertently created a standard form for decorative elements that continued for decades until adapted for more modern, long-wheelbase trucks.

Vehicle decoration spawned an industry. The trucks, imported as cab and chassis, are constructed according to the needs of the decorators. The format of the original wooden structures is maintained for newer metal bodies to create continuity of compositional techniques. Seats are decorated, interior ceilings, flashing lights, reflective stickers and of course, spaces designed for poetry.

While the transport company underwrites the cost, the motifs are selected by the truck driver, who needs to be encouraged to undertake gruelling journeys on badly-lit and dangerous roads. The decoration industry is also an art school with apprentices learning from ustads.