In the wake of its 70th anniversary there has been a spurt of books on Partition. Most of them are unbiased. So is a recent work by debutante author Aanchal Malhotra titled Remnants of a Separation: A History of the Partition through Material Memory, which comes as a refreshing change as it unravels memories by attaching them to physical objects. The young woman, who studied fine arts at the master’s level, turned into an anthropologist and oral historian when she interviewed those who were forced to migrate from one side of the newly carved border to the other. Most people who crossed over nursed the hope that they would soon be able to return to their houses, which sadly was not to happen.

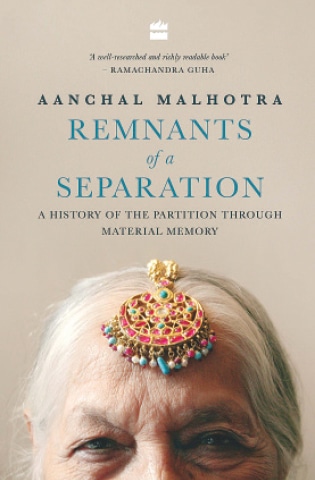

Though young Malhotra’s family had migrated from what became Pakistan, she never gave much thought to this tumultuous chapter in the subcontinent’s history until she saw her paternal grandmother hunched over her bed, carefully examining coins that she had brought with her. There were rupees, annas, paisas, takkas and dhelas, which she had treasured in a blue velvet pouch. What would interest Pakistani readers is that the coin of the largest denomination had ‘One Rupee India 1920’ embossed in bold letters in English and Urdu on one side. Malhotra’s dadi also showed her the maang teeka, which her own mother had brought along hidden in her clothes. The lovely jacket of Malhotra’s book displays the precious — both in terms of value and nostalgia — piece on the forehead of the old lady who treasures it.

Malhotra then takes us to her maternal grandfather and his elder brother’s house. They had brought a round vessel, called a ghara, in which their mother used to make lassi. The ghara continued to do the job in its new home for decades. Malhotra’s nani, meanwhile, had brought a metal yardstick called a gaz which was again put to use measuring fabric.

A debutante author reconstructs Partition through the things fleeing migrants took with them from their homes

Referring to her own ‘conversion’ — from viewing Partition as a moment in history to becoming emotionally engaged with it — the author says that flashing before her eyes were simply black-and-white images of refugees crossing the border, seeking refuge in tents and cooking meagre meals in makeshift kitchens. “But as my grand-uncle spoke about the Great Divide as something they had seen, witnessed, survived, it made my skin crawl.”

As many as 18 more people were interviewed by Malhotra. She talked to them, often in more than one session, and in the company of younger members of their family who would help fill in the blanks. The objects brought by the narrators often triggered their memories, and what a variety of objects there were — fading sepia-toned photographs, utensils, a hand knife for cutting vegetables and (if need arose) for self-defence, identification certificates, a haavan dasta [pestle and mortar], a pashmina shawl and a peacock-shaped bracelet, to name a few.

Malhotra interviewed an elderly Muslim, Nazeer Adhami, who ran away from his home in a suburb of Delhi when it was being ransacked by rioters in 1947, only to return when there was a semblance of normality. He and his family members had worked for the Muslim League, but culturally they felt they were different from their co-religionists in the new country, which was why they stayed back. His memorable belongings were three photographs of his hockey team at Aligarh Muslim University that he had taken off the common room wall.

The story of Narjis Khatun, who hailed from an affluent and influential family in Patiala, is different. When the Hindu and Sikh refugees from across the border decided to avenge their sufferings, 10-year-old Narjis and her family members escaped at night to Samana, 16 miles away. It was a town punctuated with shrines belonging to Shia Muslims. Her father’s family was well settled there. But things changed suddenly and when her family decided to leave for the neighbouring country, her father entrusted a box of valuables — jewellery and clothes embroidered with zari — to his friend Ram Dutt. Months later, much to everyone’s surprise, Dutt handed over the amaanat to its rightful owner when he and Narjis’s father met on the unmarked and unguarded border.

Another highly interesting character is R.J. Taylor, a London-based, 94-year-old former Indian army officer, who was born in India of English parents. He was homesick and proudly showed Malhotra his old photographs taken in India. His memory had faded, but his acquaintance with the accents and pronunciations of desi people was very much intact and he could sing the hit film song of the late 1940s, ‘Aana meri jaan Sunday ke Sunday’, with ease.

Malhotra has the knack of a storyteller; she narrates and describes the people, the objects and the associated memories with remarkable ease.

The reviewer is a senior journalist and author of four books, including Tales of Two Cities

Remnants of a Separation: A History of the

Partition through Material Memory

By Aanchal Malhotra

HarperCollins, India

ISBN: 978-9352770120

386pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, April 15th, 2018

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.