In 2015, I met Ifat Ghazia, a filmmaker from Srinagar, at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), where I was enrolled in a Master’s programme. We often spoke about her experience of growing up under occupation and my personal affinity with the troubled land of my ancestors.

Through the ‘Kashmir Solidarity Movement’, a student society at SOAS, I met other young Kashmiris living in London. My friends introduced me to other young Kashmiris on Facebook and Twitter, who were kind enough to agree to be interviewed.

Kashmiris who grew up in the 1990s saw more death before their tenth birthdays than most people see in their entire lifetimes.

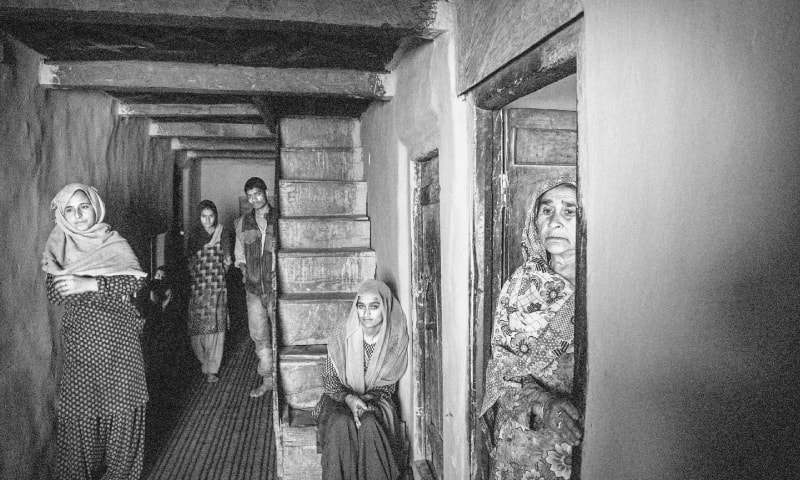

The 1990s saw some of the most turbulent days in Kashmir’s history. Crackdowns were common and families would spend the nights huddled in the dark to hide from soldiers patrolling the streets. From the earliest memories of her childhood in Baramulla in India-held Kashmir, Rabea Bukhari recalls most vividly the darkness. “The mere barking of dogs would make people turn off their lights. With the setting of the sun, only fear would inhabit the streets,” she says.

The image of a body under the canopy of a walnut tree haunts Bukhari all these years later. When she was four, her uncle, an imam at the local mosque, went missing. The family waited for a day and a night in apprehension. Bukhari remembers going to see her grandmother and finding her sitting under a tree with mourners surrounding her uncle’s body. “His daughter wailed inconsolably. I bundled myself into my grandmother’s lap. I didn’t cry. But that day, I felt the terror of the conflict seep into my bones.”

Manzoor Sadiq*, 28, is studying for his PhD at an Indian university. His childhood friends are buried in a cemetery, a few metres from his house. For him, their graves are a daily reminder of the brutalities of an occupation.

Far from home, young Kashmiris are still haunted by their childhood

The memory of one night from back in 1994 remains with him. “We were woken up by a loud bang and shrieks from outside. The windowpanes broke. We made our way out and in the darkness. We could see that some houses in our neighbourhood were ablaze.”

Sadiq and his family managed to escape but returned in the morning to find a massacre. “Seven members of a family we were very close to had been burnt alive. Three of them were my age. We had played together in each other’s homes.”

Twenty-seven-year-old PhD student Mehreen* studies political science at a university in New Delhi. She finds it problematic when words like ‘unrest’ are used in the context of India-held Kashmir. “Unrest gives the impression of a temporary disturbance of sorts. And Kashmir is anything but. To not look at violence and the resistance to it in a continuum is to not understand Kashmir at all.”

She insists her childhood in Kashmir was “normal”. “Much of it seemed normal back then; the curfews, the crackdowns, the constant sound of gunfire. Violence is the norm in Kashmir. It is only when you look back as an adult do you recognise the exceptional ways in which you were denied a dignified life.”

Much of her childhood was spent at her grandmother’s house. She still remembers the patterns carved into the wooden ceiling she would lay staring at, when the Indian army patrolled outside. Her earliest childhood memory is from a cold winter day, when she was five. “I was walking to my grandmother’s house with my father, when we heard gunshots. We began to run, diving down on the ground with our faces in the snow. My father covered my body with his and we lay there freezing, until there was a break in the firing.”

In 2002, they burnt her home to the ground. Militants had taken refuge in a neighbouring house. They exchanged gunfire for hours and once they were done, they set fire to the houses. “I returned to find rubble where my childhood home once stood. Thirteen houses were razed to the ground. That was the day I was certain there was an us and them,” she says.

Memories of violence

For many Kashmiris of this generation, the term ‘crackdown’ brings up harrowing memories of violence, loss, chaos and displacement. “A crackdown was collective punishment for an entire village when the Indian army would cordon off the area and force men to assemble in a particular place. Soldiers would then set off on a ‘search operation’ barging into homes looking for Mujahideen or arms and sympathisers,” says Bukhari. “A day of crackdown meant a day off from school and such days were frequent,” she says.

Thirty-year-old engineer, Irfan Jamil, says the experience of crackdowns represents so much of what life was like for a child in India-held Kashmir. “Men and boys were paraded in a local ground. Often, we would start playing with our friends who had also been brought there when suddenly the soldiers would grab some men and start beating them mercilessly. Scared, we would run back to our fathers, burying our faces in their clothes, trying not to look at the soldiers,” he says.

Twenty-five-year old filmmaker from Srinagar, Ifat Ghazia, had just started school in 1995, when her whole world turned upside down. Some militants were hiding in the shrine of Shiekh Noordin Noorani in Charar-i-Sharif in District Budgam, where Gazia lived. A siege was declared and the army told residents of the area to evacuate their homes. “We only had time to pack a few clothes,” she recalls. “I remember crying because I had to leave my toys and my tricycle behind. For months, we lived as refugees at the edge of the town.”

The army threw gun powder from helicopters and then burnt the whole town to the ground. The wooden houses and the centuries-old shrine burnt for days. “We sat watching from a hilltop. Burnt pages of books flew with the wind, our ancient history was deleted just like that. [Everything] changed forever.”

Heroes and Villains

For children in other parts of the world, villains and heroes live in fantasy worlds and come alive only on television shows and in comic books. But for Mehreen and her friends, they walked the streets and entered their homes. “I remember the fear of the uniformed men who barged into homes unannounced, leaving everything in a mess. Our things broken or stolen, food strewn on the floor.”

If Indian soldiers were villians, for Mehreen, the militants were heroes. “I don’t know if the adults saw them the same way but, as children, we were in awe of the militants.” It was exciting to spot a mujahid on the street. “We even looked up to the ‘mehman mujahideen’ [guest mujahideen] with great respect. Of course, as children we understood very little of history or geography.”

The mujahideen were heroes for young Manzoor Amin, too. “Back when I was unaware of the nuances of the conflict, I had a strong urge of joining them. Then, one by one, we saw young men going away and never returning.”

Ifat says she never played with dolls or miniature kitchen sets like girls in other parts of the world. Her toys were wooden guns that her cousins made for her. Her mother gave her the name Ghazia, which means warrior woman. “We rarely played outside but when we did, we didn’t play hide and seek but wars and soldiers. We grew up to become ‘normal’ adults but the impact of violence stays with us.”

An ‘enforced’ peace

Many outside India-held Kashmir describe the years between 2000 and 2007 as a period of relative peace, but the young Kashmiris who spoke to Eos argue that there can be no peace under occupation. Bukhari says while these years saw less active confrontation between Kashmiris and India, the enforced disappearances and the high-handedness of the Indian military ever-present in civilian spaces and the harassment of the population continued.

Manzoor says there was an ‘enforced’ peace in these years. The number of militants was reduced to a few hundred and the encounters became less frequent. With a new government in India-held Kashmir, there was less civilian harassment and fewer crackdowns. But the militarisation went deeper and the number of military camps increased. Manzoor argues that amid the ‘relative lull’ India did not make any efforts towards an actual resolution and discontent continued to simmer.

Jamil agrees, saying: “Every resistance sees periods of intense activity followed by quieter periods. Many Indian analysts like to paint a very rosy picture of these years but the protests, killings, torture and enforced disappearances continued.”

There is no more or less peace in India-held Kashmir, Mehreen says. “If peace is a dignified life with the absence of violence and coercion then peace can only come with Azadi [freedom]. ‘Development’ cannot wash away blood.”

A fresh wave of violence

In May 2008, Indian authorities transferred over 100 acres of forest land to the Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board (SASB) to set up shelters and facilities for Hindu pilgrims. It came as no surprise to Manzoor when in 2008, widespread violence erupted in the valley once again. “It was an uprising, an intifada” he says.

“People resisted. People united. Peaceful demonstrations were responded to with bullets. But with each killing the cry for Azadi grew louder,” he says.

On a particularly turbulent day, when a curfew had been announced by the government, Jamil’s father needed to visit the hospital. Jamil recalls gathering his father’s medical papers and taking him to the hospital. “We were stopped by security forces just a kilometre before the hospital and when we tried to explain the situation they began to abuse us,” he says.

Both father and son were made to lie down on the roadside. “More men joined in and one of them slapped me across the face. Death would have been sweeter at the time. How I wish no son sees such a day.”

Finally, after an hour of being subjected to verbal and physical abuse they were let go only to be stopped again. “My father’s pain was increasing. I begged them to let us go and somehow we reached the hospital alive.”

The incident shook Jamil. He couldn’t sleep for days. “I had exams but couldn’t study. I just wanted to pick up a gun and hurt those who had insulted my father. But my mother forced me to pack my bags and go back to college.”

Today, his cheerful demeanour belie the anguish of those days. “I would weep in isolation. I saw the exam date sheet but couldn’t open my books. I kept reading A Country Without a Post Office by Agha Shahid Ali and was ready to leave to become a fighter. Azadi was the only thing on my mind. I wrote it all over the walls, on the door, in my books, anywhere I could.”

According to Manzoor, the brutal state response to protests in 2009 and 2010, inspired greater numbers of Kashmiri youth to start joining the armed resistance once again. “Insurgents were openly challenging the state without masks and were making full use of social media.”

During this time, Burhan Wani became a household name. “Whenever an insurgent is killed, people attend the funeral in thousands and when Burhan was killed people offered funeral prayers for days. Police fired at civilians, killing dozens. This led to more protests and more people were killed. The killings have not stopped since. This is a perfect example of incremental genocide in Kashmir.”

Changing perceptions of Pakistan

Pakistan often refers to Kashmir as its ‘jugular vein’, but many young Kashmiris such as Mehreen think Pakistan’s support has been ‘inadequate’. Once, Kashmiris saw a merger with Pakistan as a viable solution to the conflict but today few young people support this idea. “Our elders used to say they wish one day Kashmir becomes Pakistan and Pakistani tanks roll over their graves. Such was the love for Pakistan. But this has changed over the last 20 years,” says Jamil.

“Once the word Pakistan was graffitied on walls, today it has been replaced with Azadi,” he says.

Bukhari argues that the people of India-held Kashmir have always pinned their hopes on Pakistan. “For us, Pakistan is a support system, a reservoir of hope. Despite its internal political chaos, we Kashmiris have never given up on Pakistan. But this might change, unless the government rises to the occasion and shows unflinching support to the Kashmir movement.”

Manzoor says there have been inconsistencies at the government level but as a nation Pakistan has always stood by Kashmiris. “There has always been a sentiment in Kashmir for a merger with Pakistan. It has wavered over the years but it is now on the rise again,” he says.

Aspirations for Azadi

The experience of growing up under occupation shapes the perspective of young Kashmiris in ways that set them apart from youth in other parts of the world. “Occupation gets to define who we are to become,” says Manzoor.

“Some become insurgents, some write resistance poetry, some join the civil resistance and others report on the atrocities or try to provide relief. Hence navigating personal and collective ambitions together,” he adds.

Jamil says there is a positive side to the Kashmir story on youth. “We are perhaps the most learned community in India. Every Kashmiri is politically aware. We know the works of Iqbal and Plato. We discuss Nietzsche and Edward Said.”

Bukhari says growing up in India-held Kashmir, she always felt twice her age. “Growing up with conflict has bestowed us with political maturity but robbed us of so many pleasures of childhood and of life. Perhaps sorrow adds years,” she says.

For most young Kashmiris, all dreams and aspirations stem from their experience of growing up in a conflict-zone. “All our issues — whether unemployment, radicalisation, social ills — stem from the primary issue of occupation. If occupation ends, the Kashmiri youth will find a way to resolve our issues,” says Bukhari.

*Names have been changed due to safety concerns

The writer is a freelance journalist.

She tweets @Shiza_Malik

Published in Dawn, EOS, May 27th, 2018

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.