LET’S start with a basic truth: a depreciation in the exchange rate is not the end of the world. Nor is it, by itself, a sign of a calamity. Exchange rates fluctuate normally in almost all countries.

In some cases, the movements are driven by local factors (such as the strength of the balance of payments), and in other cases by global factors (such as if the dollar should strengthen against global currencies because of rising interest rates in the US).

So the problem today is not so much that we have had four rounds of currency depreciation since last July. The problem is that since March 2014, when former finance minister Ishaq Dar managed to get the exchange rate up to Rs98 to a dollar, from where it gradually slid to Rs105 till his departure, the country was basically operating under a managed exchange rate regime.

That invisible peg was gone once Mr Dar was pushed out of office, but by then the inevitable imbalances had built up to unmanageable proportions.

Keeping the exchange rate imprisoned within a narrow band is very bad economic policy.

For perspective, take a look at what happened next door, in India, during the same years. In 2013, when the PML-N government came to power, the India rupee was at INR58 to a dollar. Today it is at INR67.6 to a dollar, having touched a peak of INR68 to a dollar at the end of May. But a surprise hike in the key policy repo rate in early June gave it a little more strength.

The Indian rupee’s journey to INR68 to a dollar (a decline of 17 per cent compared to the decline of 14pc that the Pakistani rupee has seen from 2014 till today) was not a straight line.

A graph plotting monthly average exchange rates for the Indian rupee, for instance, goes up and down from 2013 till the present, with many real-time course corrections along the way.

In the last six months, there is an INR3 decline, attributed by analysts in India largely to the growing strength of the dollar due to two hikes in interest rates there of 25 basis points each, one in December and another in March.

Uncertainty lingers over the prospect of further hikes in 2018, what other central banks refer to as the “normalisation of interest rates”, following years of record low rates after the great financial crisis of 2008.

This may sound complex, but it is in fact an ordinary phenomenon. The exchange rate should, if things work as they are supposed to, be adjusted in real time based on market signals of supply and demand.

If a basket of global currencies, those of the country’s largest trade partners, is rising, it is normal to expect that there should be a depreciation of the rupee.

If that doesn’t happen then we all have a problem, because the misalignment in the exchange rate will have to be corrected at some point, and the larger it is when that point in time arrives, the greater the jolt it will deliver to the economy.

Some might recall the days of fury back in late 2013 and early 2014. Dar went on a rampage against exporters, demanding that they close their net open positions quickly and bring their export proceeds back expeditiously (the law allows them up to 90 days to close these positions), or else they might be burned because, as he threatened, he had every intention to bring the rupee down.

In December 2013, he took to the airwaves, announcing in TV interviews that the rupee would hit 98 to a dollar. It was, at that time, at Rs105 to a dollar.

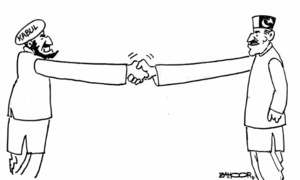

Shortly after that, in late February 2014, two tranches equalling almost $3.1 billion arrived in the reserves from a ‘friendly country’, later revealed to be Saudi Arabia, and the rupee shot up to 98, where the minister had promised he would take it.

Then came the warnings from the State Bank. “Reliance on one-off inflows and foreign loans may provide short-term stability, but share of private financial flows need to increase consistently to achieve long-term stability,” said the subsequent monetary policy announcement. Translation: ‘we are not impressed.’

The rupee gradually fell back to 105 to the dollar, but there the declines stopped. The central bank did not intervene directly to support it at that level, by selling dollars in the interbank market to make up for temporary shortages, relying instead on whispered ‘advice’ to treasury heads of major banks to refrain from buying whenever the value of the dollar went above 105.50 or thereabouts in the interbank market.

The illusion of stability was sustained, but at a steep cost that is now coming in. For some reason, Dar had it in his head that a stable and strong rupee is a good thing (and perhaps in some cases it is), and must be maintained at any cost.

Last July, when the first crack in the edifice that he built appeared in the form of a sudden depreciation, he revealed his hand in the angry tirade that followed, in which he shouted that a 3.1pc depreciation of the rupee means a “public debt loss of Rs230bn”. We’re still not sure whether this meant a hike in debt service obligations for external debt or a hike in debt stock.

Keeping the exchange rate imprisoned within a narrow band is very bad economic policy. It is much better to let it fluctuate as you go, finding its own way. That way you avoid disorderly shocks to the economy, and prevent speculative sentiments from building up, and provoking an uncontrollable rush to the dollar.

If other aspects of the economy have to adjust in response to these exchange rate movements, then let it be. Living with a lie never works, and economic management is no exception.

The writer is a member of staff.

Twitter: @khurramhusain

Published in Dawn, June 14th, 2018