Earlier in May, a rumour made the rounds on the messaging service WhatsApp claiming that Pakistani neuroscientist Dr Aafia Siddiqui had died in a US prison.

“The great daughter of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, #DoctorAafiaSiddiqi has passed away and now she is free of this world and American imprisonment. The daughter of Islam, the daughter of Pakistan Dr Aafia Siddiqi spent 5,390 days in an American jail and is no longer with us,” read the hoax message that went viral on May 20.

A few days later, Pakistan’s Consul General in Houston Aisha Farooqui rejected the information as baseless and false after a two-hour meeting with Dr Siddiqui at a US federal facility.

However, Chief Justice of Pakistan Mian Saqib Nisar directed the government to contact the US authorities to verify the ‘conflicting reports’ being circulated on social media regarding Dr Siddiqui’s death.

The Facebook-owned app has 5.2 million website visits per month in Pakistan, according to a global digital report released by international social media companies, ‘We Are Social and Hootsuite’.

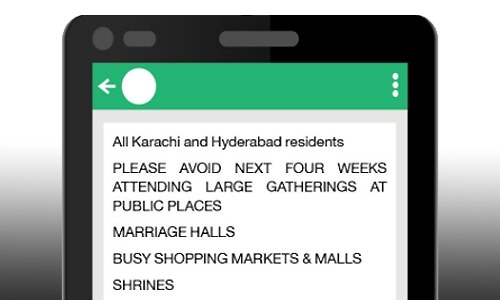

Given the volatile political climate in the run-up to the July 25 general elections and the messaging app’s popularity, WhatsApp is rife with fake news, disinformation and inflammatory messages that are almost always political in nature.

In recent weeks, information networks have been rife with rumours ranging from a delay in polls to a possible extension for the newly-sworn in caretaker government for up to three years.

“Forward as received messages disseminating false information have become a norm in the political sphere. The [WhatsApp] groups are buzzing 24/7,” Maleeha Manzoor, an active member of multiple WhatsApp groups of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) said, while speaking to Dawn.

As nearly 46m young voters are set to play a key role in the upcoming polls, the election campaign appears to have taken a digital route with the country’s major political parties amassing several WhatsApp groups for coordination, to disseminate news and broadcast party updates.

“The Karachi constituencies alone have more than 20 (official) groups and all the party’s information secretaries communicate to workers on the platform, especially in rural areas where WhatsApp works faster than Facebook or Twitter,” added Ms Manzoor.

A few days ago, she pointed out, party workers brought to the leadership’s attention rumours about former Sindh Assembly deputy speaker Shehla Raza leaving the PPP. “The false news was immediately refuted and was not spread further. This [rumours] has become a frequent problem,” she regretted.

Since conversations take place within private groups on WhatsApp, political parties and journalists are increasingly concerned about curbing the spread of false information to the public at large. The end-to-end encrypted messages on the platform are circulated across chats before the news reaches mainstream media, creating confusion and uproar among the masses.

A few days before June 6 — when the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) claimed it would announce its election tickets — an unverified list of the PTI candidates started doing the rounds on WhatsApp and soon gained traction on other social media platforms.

“God willing we will announce the majority of candidates for constituencies on June 6. Lists circulating on social media and through other sources are fake and do not believe them,” PTI information secretary Fawad Chaudhry had tweeted. However, despite the party’s official statement, various versions of the lists continued to be circulated on social media.

“We have thousands of members connected on multiple WhatsApp groups. It is not possible to control the flow of information. Therefore, we have an active social media presence to regularly update party activity. But since WhatsApp is personal and easily accessible, people rely on it more,” PTI’s social media secretary Dr Arslan Khalid told Dawn.

The privacy factor

In spite of WhatsApp’s repeated privacy stance emphasising end-to-end encryption — that prevents a third-party from intercepting conversations — digital rights experts are convinced that the platform can be used to manipulate and access sensitive information.

Last year, activists of the Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) made locality-based WhatsApp groups to send out VPN links directing users to the live stream of their Faizabad sit-in. One of the groups — called Khatm Nubuwat Defence 4 — made for residents of DHA Phase IV in Karachi comprised over 100 participants. The added users, however, had no idea how their phone numbers and residential information had been accessed.

“Anything said online will be accessible one way or the other. People are increasingly using screenshots to file defamation cases and devices of journalists and activists are being stolen to access private chats,” digital rights activist and lawyer Nighat Dad told Dawn.

Given the crackdown on freedom of speech and dissenting voices in the country, Ms Dad urged the WhatsApp group admins to be mindful of the content being shared. “One message can pose a threat to someone. And this has happened in Pakistan,” she warned, adding that people should make an informed decision during the election season and not react to inflammatory messages without verification.

Referring to circulation of fake manuscripts of Reham Khan’s book on WhatsApp, Bolo Bhi director Usama Khilji said that people had fallen down the rabbit hole of ‘forward as received’ messages.

“Political discourse has been reduced to ‘I heard it so I know it’ in Pakistan. Although it is difficult to track where the information is spreading from, it should be in any case doubted first,” he asserted.

Published in Dawn, June 16th, 2018