Jinnah International Airport appears to be a regulated place: passengers boarding domestic and international flights keeping to their schedules resolutely, making queues, trooping from one gate to another through security checks. The scene is measured and timed.

One would not imagine that amidst the seemingly ordered façade of routine and movement, lurk discreet men known as khepias. A khepia could be standing behind you at the check-in counter or sitting next to you in the plane, without being noticeable. For these men, airports serve as portals not only of travel but also for private business.

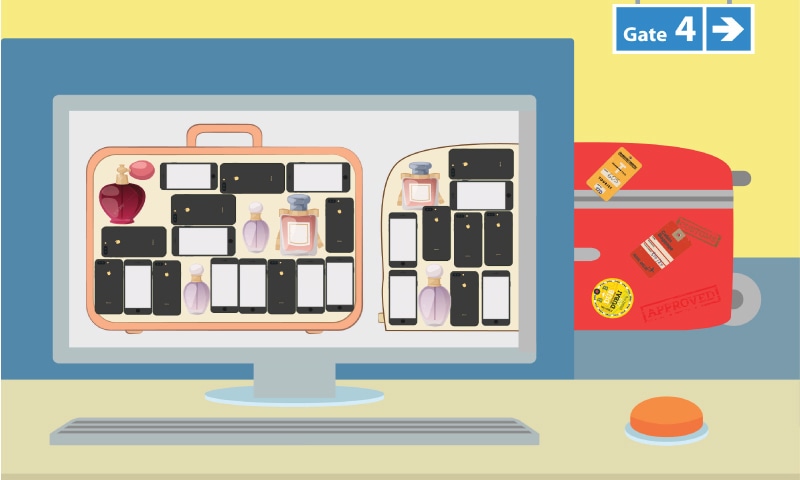

Simply put, khepias are involved in the activity of exporting or importing freight (‘khep’ i.e. goods), through illegal means. In every flight from Karachi to Dubai there are, on average, eight khepias, with the number rising to 20 at times.

It may be risky business to smuggle duty-free goods across countries, but khepias have their ways. A few divulge their secrets to Eos...

The goods range from raw materials used in manufacturing to jewellery and high-end clothes to cigarettes and electronic gadgets. This means they are exempt from tax which would otherwise be charged to businesses exporting or importing goods formally. The exempted ‘tax’ ends up in the pockets of not only the khepias, who travel across international borders to deliver these goods, but certain official actors from within the bureaucracy who abet these khepias also pocket the money.

Ghazi, 25, belongs to the Bantva Memon community and has been a khepia for over half a decade. He shares the inner workings of his profession.

According to him, he earns an average of 10,000 rupees to 12,000 rupees on every khep. “We don’t purchase anything and work as couriers, i.e., we transfer things from one place to another. It’s the same as cargo. It is not a part-time or full-time [job], rather the flight can be anytime.”

The profit margin is enough to meet family expenses, thus khepias can get by without another fixed income. But in several cases, if they do run other businesses they are usually interlinked with khep dealings.

THE ‘ALL-ROUNDER’

Khepias belong to all walks of life and are from all major communities living in urban centres of Pakistan, but according to Ghazi, Punjabi and Urdu speakers hold an edge over others when dealing with airport officials in Pakistan.

The business is all about trust and ‘goodwill’ and a khepia inherently needs good public relationing skills and tact. For instance, a party from Dubai will entrust only somebody they perceive as reliable; in case the khepia runs into trouble with customs or the goods are confiscated, he should be able to take care of the situation and ensure the delivery of intact goods.

“Right from entering the airport gates,” Ghazi says, “up until getting into your seat, everything is bribed. The Airport Security Force (ASF) stops us at the gates, of course, after noticing that our ‘luggage’ is in excess of the permissible 30kg but, after a small bribe of 500 rupees, they let us pass.

“Some of us have become familiar faces for them now; they speculate what we are doing and do not question as long as they receive their bribes. Once we’re inside, the Anti-Narcotic Force (ANF) personnel take their share and let us pass for another 500 rupees.”

Items exported from Pakistan in the form of khep, usually to the Middle East and mostly the UAE, vary from women’s branded clothes and foodstuff such as ice cream, rabrri (a traditional dessert), packaged spices and other perishable items. Two things that Pakistani customs officials especially keep an eye out to immediately confiscate are cell phones and gold items.

Going through customs is not easy.

“At Dubai customs, [if we are taking ice cream in khep] the officials will eat it as a checking procedure and send it for laboratory tests. Sometimes, customs officials withhold the goods and keep our visa information and contact numbers also. If the ice cream is held for lab tests, it is not returned. But if we are given a clean chit then we consider our profit to be that we were not caught for any illegal activity.”

At Dubai airport, items which look suspicious are marked by barcode chips which beep when you exit the luggage collection lounge. The fine for removing the barcode chip is 100,000 United Arab Emirates dirhams.

The riyal, dirham, British pound and US dollar are the main currencies which khepias deal in in Dubai. On average, a khepia carries 10,000 US dollars while travelling to the UAE. “There are people sitting in the UAE who buy worn-out foreign currency banknotes which are not exchangeable in Pakistan. These are bought by local money changers in Karachi at below face value and exchanged at market rate later.”

How do khepias escape scrutiny and penalty as a slight mistake could land one in big trouble? There are also cases reported regularly where people are caught carrying illegal goods and drugs, while trying to deceive the concerned authorities. Ghazi comes back to the idea of trust when questioned how he assures he is not carrying suspicious goods in his khep. He says, “I am pretty satisfied with the goods I carry because those who we work with have been in this field for decades and are trustworthy.”

So far, he recalls only one huge case — the ‘hazelnut case’. The nuts had drugs in them; they were transferred from Karachi to Dubai, clearing customs safely, only to be discovered at the Sharjah border during a random check. Out of the three men involved, one was awarded 15 years; two were released after a year and were given a green check (which confers that they can go back again). The case was reported in the Khaleej Times.

About 50 percent of the clients belong to commercial entities. Ghazi’s clients even include Indians. “I have to drop several things for them in Dubai and they send queries over WhatsApp,” he says.

Being a Pakistani passport-holder makes it rather difficult to get visas from developing economies. Paper requirements from Middle-Eastern countries are not easy to get done and also cost a good fortune.

A typical tourist or visit visa for the UAE (valid for up to two or three months for multiple entries) is obtained from a local travel agent. Usually, a three months’ multiple entry visa costs around 60,000 rupees, whereas the one with two years of validity costs 450,000 rupees as it is a company visa or employment visa, and approval from police and medical test is needed as well as CNIC in English. “I had a two-year visa so in the eyes of Dubai authorities, I am an employee of Dubai. I made a maximum of eight round trips to Dubai in a month,” says Ghazi.

Right from entering the airport gates,” Ghazi says, “up until getting into your seat, everything is bribed. The Airport Security Force (ASF) stops us at the gates, of course, after noticing that our ‘luggage’ is in excess of the permissible 30kg but, after a small bribe of 500 rupees, they let us pass.”

Ghazi, like others from Karachi arranges a one-way ticket and from Dubai; the return ticket is fixed via WhatsApp by his travel agent in Karachi, upon successful delivery of goods and receiving the goods to be delivered back in Karachi. Bed space is usually to be arranged by oneself. Whereas, “If we are working for someone who is paying us at around 5,000 per trip then this whole hassle of accommodation rests upon his shoulders.”

Every khepia prefers Dubai because currency movement from Pakistan to Dubai is beneficial and many Pakistanis are based in Dubai as it also has the most relaxed visa policy.

Pakistani cigarettes are exported by khepias all over the world. Gold Leaf and Capstan are the hot running brands. One can’t send cigarettes in cargo to and from Pakistan and only a carton (popularly called a ‘danda’) is allowed to be taken to Dubai. The dealer in Dubai collects them and sends them via cargo to the US. Everyone along the way takes their share; it’s not just in Pakistan.

The overall size of this economy only in Karachi is over a billion rupees, according to Ghazi.

“I alone bring five million worth of goods in a month. The goods which come through this are those which have an urgency in the market; other items can come through as cargo,” he says.

Under the watchful eye of intelligence officials, there is never a guarantee of things going smoothly even for an experienced khepia who maintains good contacts through networking. There can be many snags along the way to upset the apple cart. Rivalry among the various agencies can sometimes make an old business suffer. “Custom Intelligence is also active in this regard.”

When he gets a tip from Karachi airport that a director customs is on round, Ghazi won’t board the plane even if he has been issued a boarding pass. “I will miss the flight somehow while waiting for it to take off in the washroom, etc.”

“In one month, I earn around 30,000 rupees whereas in this field the minimum on this route is 20,000 rupees and maximum is 40,000 rupees. Risk factor is huge in this business,” says Imran.

Pickup and delivery of the goods is also a subject of great importance in this business. The client can send goods either to the airport or directly to a khepia’s home or shop.

Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh and China are popular destinations after the UAE.

THE PAAN MERCHANT

Imran is 32 and a college graduate. He belongs to the Urdu-speaking community and has been in this business for more than three years. He mainly focuses the khep activities in the Far East, regularly travelling to Bangkok.

According to him, each flight to Bangkok and other popular Far Eastern destinations include an average of five khepias. “Experience is required as customs needs assurance from a senior dealer. It’s a ‘hawai rozi’ [uncertain income].”

Whereas Malaysia and Singapore have a market for Pakistani cigarettes, Imran brings home the item that goes hand-in-hand with cigarettes at every roadside stall in Karachi: paan leaves. He brings an average of 90kg of ‘paan’ (betel) leaves from Bangkok. From Karachi, he takes jeans, used clothing, shoes, etc., charging his clients 500 rupees per kg for a trip from Karachi to Bangkok. Aside from paan leaves, on his return from Bangkok, he brings cosmetics, auto parts and artificial jewellery. His total earning per flight is between 8,000-10,000 rupees.

Citing the rising airfares, he claims the khep business is not for everyone. “It’s not for beginners. Newcomers need reference from the experienced khepias to build a reputation of authenticity and genuineness. And that is how it goes.”

THE COSMETICS TRADER

Umer, about 30 years of age, is a cosmetics trader and wholesaler of high-end cosmetics and skin care products such as perfumes, lipsticks, foundations, etc. supplying to upscale stores and supermarkets located in Defence and Clifton areas of Karachi. He is also a general trader in khep items.

This is a family business for Umer. He was earlier working with his father and after his demise, is now running the business on his own. He explains, “The high-end cosmetic brands can only be obtained from Europe and North America, which are relatively hard-to-travel-to regions for an average khepia — the visa and travel fares for the regions make it impossible for the local khepias. Moreover, though these goods are small in quantity, they are expensive and fragile.”

When asked who replaces the role of the khepia in this case, he unhesitatingly responds, “I have contacts with the airhostesses, who tell me their destinations on WhatsApp groups, prior to their departures.”

Cash is delivered to the relevant airhostesses prior to the flight’s departure, with the demand list already discussed on WhatsApp. “We remain in contact via WhatsApp while she is shopping from duty-free stores and supermarkets. This way I know what she is buying. I obtain the receipt of the said purchase, and later tally it with the goods purchased.”

The carry charges which he pays the airhostesses on average are 10,000-15,000 rupees depending upon the demand and the goods being brought. He gets an average of 35-40 percent profit margin. Dealing in very selective brands and selective clients, in theory, means less competition and more profit.

EASY COME, EASY GO

Earlier, there were less regulations at the customs. The ‘green channel’ was introduced by Nawaz Sharif in the late 1990s to encourage this trade. “All the old guys have now switched to their own entrepreneur shops and are doing the business legally,” says Ghazi.

“For a laptop that moves out of Pakistan to Dubai for warranty claim, I charge 900 rupees. For bringing Apple Mac Book from Dubai I charge 5,500 rupees.”

The expensive vegetables and fruits such as avocado and kiwi that are used in five-star hotels and sold at posh departmental stores are also supplied by khepias from Dubai as they are perishable and can’t take the long journey via ship. “Vegetables are packed in thermopile boxes which contain ice and I charge 600 per kg for this. There is no duty on vegetables,” explains Ghazi.

Jinnah International Airport may be the hub for the khep business, but this duty-free import/export takes place at every international airport in Pakistan.

“When I started my work there were less restrictions as compared to now. Modern technology on cheap prices was available to Karachiites but due to restrictions it’s not the same as all these things come from port and with heavy taxes. Chinese companies have flooded the markets with their one-year warranty. The companies pay hefty amounts of under-the-table-money to get licenses so they can’t offer good quality. The consumer with limited money has to sacrifice quality for quantity.”

*Names have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals

Published in Dawn, EOS, June 24th, 2018

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.