It hasn’t even been a couple of days since the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) announced the detection of complex organic material originating from a moon orbiting Saturn that can probably sustain some life form. And understandably, the euphoria and excitement of this discovery has been felt across the world, in scientific communities and among ordinary citizens.

But little is known about the Pakistani man who, along with Prof Dr Frank Postberg, has co-led a team of world-class scientists that published this groundbreaking research in the prestigious science journal, Nature.

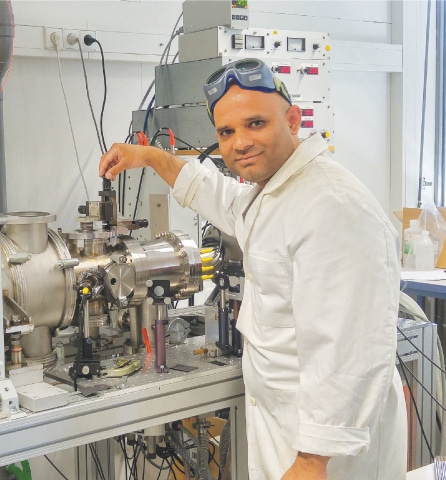

Meet Dr Nozair Khawaja. Hailing from a small rural area of Wazirabad, Khawaja belonged to a middle-class family. He left home first to complete his Master’s degree in Space Science from the Punjab University, before heading to the Heidelberg University, Germany, to pursue a doctoral degree. And it was in Germany that he immersed himself in planetary research and began working on NASA’s space mission “Cassini towards Saturn.”

Eos presents the first interview Dr Khawaja has granted to any Pakistani publication.

Eos meets the young man from the small town of Wazirabad whose groundbreaking research into one of Saturn’s moons has been published in the prestigious science journal Nature on June 28

Dr Khawaja, the world is fascinated by your new discovery but what makes it most exciting for you?

Well, to me, everything is very exciting, but for public interest, I would like to summarise. We found large and complex organic molecules from Enceladus. Previously, the mass spectrometers (CDA & INMS) onboard the Cassini spacecraft found small organic compounds coming out from Enceladus’ subsurface ocean. But this discovery is the very first detection of very large and complex organics coming from the extraterrestrial ocean world.

So, can Enceladus be colonised for the survival of human civilisation in future?

Space colonisation or space settlement should be understood as permanent human habitation on any other planet. And since Enceladus is very far from the Sun and the surface temperature at Enceladus is extremely cold, approximately -200 °C, which means that human colonisation of Enceladus is not possible.

The large and complex organic molecules that we found could have been contributed by non-living or living sources. We cannot say for sure that the origin of these molecules is living organisms, nor can we say that that life exists on Enceladus. Instead, we proposed that these molecules originated from hydrothermal vents inside Enceladus. Such a hydrothermal system also exists in the Earth’s ocean where microbial life exists. Therefore, the origins of these molecules are undecided but they have astro-biological potential.

Beyond scientific jargon, can you elaborate on why Enceladus is so interesting?

Actually, Enceladus seems to be a potential habitable place in the solar system but there is no evidence of any form of life, so far. All we are searching and discussing about Enceladus is the subsurface ocean on this moon where temperature is approximately 90°C.

For general understanding, I would like to elaborate that there are three basic conditions which can support or initiate life anywhere in the universe and scientists are always interested in finding those: 1) liquid water; 2) source of energy; and 3) organic molecules.

At Enceladus, scientists found that all three basic conditions were met. And now with the latest output about the complex organics, we are pretty certain that Enceladus’ ocean is enriched with a variety of organic compounds. Together with other earlier findings, this is an indication of a habitable ocean on Enceladus. These results make it one of the potential places in the solar system to look for life beyond Earth.

The findings of the Cassini mission have important implications for NASA and ESA’s future space missions, Europa Clipper and Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) towards the icy moons of Jupiter to explore their habitability.

What was the big surprise or a spectacular discovery made by the Cassini space mission?

The Cassini Huygens mission was one of the most ambitious efforts in the history of planetary space exploration. In 2005, soon after the arrival of Cassini’s spacecraft at Saturn, scientists discovered that a huge plume of water vapours and ice-grains were emerging from Enceladus’ South Pole. This was the “Big Surprise” for scientists to see a geologically active moon in the outer solar system.

The ice-grains were rising hundreds of kilometres above Enceladus’ surface. Most of these ice grains fall back on to the moon’s surface but few of them escape the moon’s gravity and form a ring of ice grains around Saturn. This moon of Saturn harbours a global subsurface salty ocean under its ice crust, which is in contact with the moon’s porous rocky core. Scientists found active hydrothermal vents similar to “Lost City” hydrothermal vents on our Earth’s ocean.

Do you think there are any future prospects about finding life on Enceladus, and what will be its implications to lifeforms existing on Earth?

As I mentioned above, we are continuously analysing the data from Cassini and trying to characterise the material from Enceladus. Although the Cassini spacecraft did a remarkable job during its voyage at Saturn but I would like to mention that the on-board instruments of Cassini were built a long time ago, and now with the advancement of technology, we can explore Enceladus’ ocean in more detail. After the end of the Cassini space mission (September, 2017), we should go back to Enceladus with advanced instruments to see if there is extraterrestrial life.

By finding life on other planets and moons, we can explore the origin of life on Earth. And perhaps this will provide immense benefits to humans in many ways — in medical sciences, for example.

To find extraterrestrial life is a long lasting desire of humanity. Finding any life form in extraterrestrial places will change humanity’s concept about life on Earth. By finding life on other planets and moons, we can explore the origin of life on Earth. And perhaps this will provide immense benefits to humans in many ways — in medical sciences, for example.

Were you always interested in the greatest mysteries of humankind, such as the origin and evolution of life on earth?

Well, for me, these queries had always been there from an early age. But my real motivation over extraterrestrial life originally developed during my graduate school. There, I had a whole bunch of informal discussions with my friends and classmates on this topic.

In the early time, the search for life beyond Earth [astrobiology] was mainly for fulfilment of human curiosity, pretty much like all other amazing scientific discoveries in the past, which have been used for the welfare of humanity. Here, I would like to mention Newton’s three Laws of Motion and Kepler’s laws of Planetary Motion. These are merely in the common person’s mind but their impact on space exploration is everlasting. The quest for extraterrestrial life would enable scientists to know more about the conditions of early life and to better understand our present and future as well — the most fundamental requirement of a healthier life on earth.

Tell us about your childhood? Where did you grow up? What was it like trying to study science in a village? And who inspired you?

I was born in a small town of Punjab, Wazirabad. The town is famous for making knives and cutlery. I still remember that I used to finish my homework in school and loved to spend the rest of my time playing cricket, kite-flying, and climbing trees outside. But I would like to mention my grandfather’s brother, Khawaja Maqbool Ilahi, who was a role model not only for me but our entire family because of his enthusiasm and determination. He always encouraged us to seek education.

I completed matriculation from the Govt. Public High School Wazirabad; it was the only institute in the city that provided science education at school-level. Then I headed to Lahore to pursue a master’s degree from the Punjab University.

Being a member of a middle-class family, it was a daunting task to continue my education after graduation. I still remember that my parents [Mr and Mrs Khawaja Ashraf] could hardly manage my fees and other expenses while I was studying. So, after getting done with my masters, my real challenge was to support my family. I spent eight years teaching mathematics and physics in different local schools and colleges of my native town in order to make ends meet.

But, eventually, I headed to Finland and got my master’s degree in astronomy and wrote my MSc. thesis on the calibration of the COSIMA space instrument on board the ESA’s Rosetta space mission. During this project, I got a grant from Europe’s Short Term Scientific Mission (STSM) to perform experiments with the on-ground model of the COSIMA instrument situated at the Max Planck Institute of Solar System in Germany. Visiting and working with notable scientists at this institute is an unforgettable experience of my life.

You have spent most of your career working on the Cassini space mission. Would you like to share background information on the Cassini-Huygens space mission, and the launch and arrival of Cassini space craft?

Well, as you might be aware, Saturn is the sixth planet situated at a distance of approximately 1.4 billion kilometres from our Sun. It is surrounded by a system of rings, which is the most extensive ring system of any planet. These rings mainly consist of ice and dust grains. Saturn has more than 50 moons.

In 1997, NASA launched a Cassini-Huygens space mission for the detailed study of Saturn, its rings and moons. Cassini spacecraft carried a number of versatile instruments. These instruments include two mass spectrometers for the compositional study of ice grains and gas at the Saturnian System: 1) Cosmic Dust Analyser (CDA) and ii) Ion & Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS). The Cassini spacecraft arrived at Saturn in 2004. It takes almost seven years to reach Saturn.

Stephen Hawking, the world-renowned scientist, repeatedly warned about the dangers of humankind meeting alien civilisation. Would you share Hawking’s feelings?

Well, I have great admiration for Stephen Hawking, his work and thought-provoking lectures. I agree with him to some extent, but I will also strongly recommend that one has to define “alien civilisation” in a meaningful context because it is a topic of great debate.

I would also like to point out another aspect of alien life, which is more realistic and which, we as scientists, are actually concerned about. In scientific terms, extraterrestrial microbial life, if it exists, is also alien life. As far as the current space exploration is concerned, the scientific community is very sensitive and taking necessary steps for planetary protection to avoid any type of contamination from Earth to other planets and vice versa. So far, we don’t have any clear evidence of any form of alien life.

You visited Pakistan in 2017 and announced the establishment of a scientific society of volunteers as the Astrobiology Network of Pakistan (ABNP). How are you planning to take this network forward?

The volunteer network of ABNP includes scientists from Europe and the United States along with students and professionals from Pakistan. We got an overwhelming response worldwide. Dr Bruce F. Damer, Mansoor Ahmad Khan from NASA and Professor Fariha Hassan from the Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, have joined us as advisers so far. One of my co- researchers, Fabian Klenner, is also an active part of the ABNP’s Germany chapter.

My future plans include organising public lectures and outreaches in schools, colleges and universities across Pakistan to spread awareness about astrobiology. I also feel a strong desire to provide career counselling to young minds interested in astrobiology and planetary sciences. Both disciplines have a vast scope and it can accomodate students from almost every branch of science.

The interviewer is a freelance science journalist based in Quetta.

She tweets @saadeqakhan

Published in Dawn, EOS, July 1st, 2018