IF in 2013, the run-up to the election was the best of times, the days leading up to the 2018 poll are the worst of times.

Five years ago, the excitement and jubilation were palpable. Pakistan was heading towards its first democratic transition — smooth and peaceful. The PPP had completed its term — despite much turbulence and many dire warnings of an upset — and the elections promised a second, legitimate government. Finally, the country had developed a consensus on political transitions through elections and not coups or summary dismissals of governments.

Political parties in general were happy with the caretaker setups in place, and while the competition for the election was real and tough (and even ugly), there were few allegations of unfair practices and undue interference. (These were to come later.)

The PPP, despite the knocks it took and its good legislative record, had not done too well in terms of ‘delivery’. The shortage of electricity and long hours of load-shedding in Punjab took its toll on the citizenry, and consequently on the PPP’s electoral performance in the province. Corruption, thanks to a ‘vigilant’ judiciary, also extracted a price from the executive. Much of this was visible in the days leading up to the election — but somehow it still did not detract from the excitement.

Cynicism and anger are the dominating emotions rather than the hope of 2013.

Perhaps what helped was the presence of two alternatives — the ‘experienced’ PML-N with its ready team of leaders and the new, untried but popular PTI, with its promise of change. Between the old but ‘clean’ and the new and ‘clean’ leader, Pakistani voters seemed spoiled for choice.

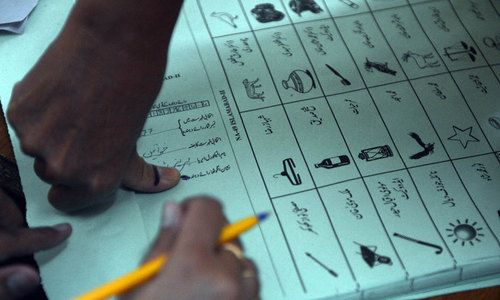

Exercising one’s right to choose was the new black. With the parties as well as civil society and the corporate sector ads pushing people to vote, the newfound enthusiasm led to a high voter turnout. Credit has to be given to the wave of support for the PTI back then, which mobilised a younger and also an older lot of previously apolitical voters. Anecdotal evidence was aplenty of expats and others who flew back to Pakistan just to vote.

But the past seems to be another country.

Pakistan is on the cusp of a second democratic transition. A second government has completed its term and the people are ready to once again elect another government without interruption or break. Yet, the overall sense is not a fraction as celebratory as 2013.

Partly this is due to the political polarisation of the past five years. Despite Shahbaz Sharif’s lurid promises of dragging Asif Zardari through the streets and forcing him to cough up money looted from Pakistan, the 2008 to 2013 period saw parties more in sync than in confrontation. But post 2013, this sense of bonhomie completely vanished. If Imran Khan took his rhetoric against the PML-N to new levels during the dharna, the others weren’t far behind.

The bitter exchange between Nisar Ali Khan and Aitzaz Ahsan during the same period is now the stuff of legend among those who cover parliamentary proceedings. And by the time Panama rolled around and Zardari returned to the country after a short exile, the PPP’s bitterness towards the PML-N seemed tame only compared to the PTI’s anger.

But the war of words between the parties paled in front of the confrontation between the PML-N and the judiciary and the military. Such was the war of words that three N wallahs have been disqualified for contempt of court while another two still await their fate.

And the Senate election onwards, the behind-the-scenes manipulation of electoral politics, according to many, is unprecedented. Overnight, the PML-N in Balochistan fell apart, ensuring that the party was reduced to a minority in the Senate it had hoped to form the majority in. The offence hasn’t let up since.

The quick divorce announced by many of the party’s representatives in south Punjab has left the party vulnerable in its provincial home ground. And in the last week alone, a handful of candidates have returned the party ticket while one has been sent to jail. Along with the disqualification of Nawaz Sharif in the middle of 2017, these developments have put paid to all the earlier predictions of his party returning to power in Islamabad.

On the other hand, the PTI has lost much of its earlier sheen of idealism as it has made space among its ranks for many electables, including some with a tarnished reputation. Imran Khan speaks less of tabdeeli and more of his party’s single-point agenda of winning elections.

But he still seems to be the only prime ministerial hopeful at the moment. For, Nawaz Sharif has been removed from this race. He now appears the angry, not-so-young man, who speaks of ideology, democracy and civilian supremacy — which would have sounded convincing (given the attacks he is facing from within the state) had he not spent four years ignoring parliament, his cabinet and his party. And he doesn’t just face a revolt from the back benchers. His younger brother, and now the party head, turns a blind eye to the elder Sharif’s blistering assaults on the establishment and the judiciary. Indeed, Shahbaz Sharif and Imran Khan sound closer to each other ideologically, if they are asked about how even the pitch is.

In the midst of all this, journalism has been equally badly hit. Divided within itself and under pressure from state institutions, there is little space for neutrality. We are read and watched not for unbiased reporting or views but for the positions we have taken.

No wonder then that cynicism and anger are the dominating emotions, rather than the hope of 2013. Some even question the process, wondering if the mere form of elections is worthy of being called a democracy. But this is an academic question, thankfully. For political parties, including the PML-N, any election is better than no elections. Indeed, those who wonder what the point of this ‘fixed’ exercise is, should ask the PML-N why it continues to fight on. However dirty a fight it is better than no fight at all.

The writer is a journalist.

Published in Dawn, July 3rd, 2018