It was September 1995 when Nadira (then Alvi) phoned me and said V.S. Naipaul was in town and that I should see him. I refused. Why, he was an abrasive, disagreeable old man who had destroyed journalist Nusrat Nusrullah in his book Among the Believers. I didn’t want the same done to myself.

No, said Nadi. I had to be myself and since I always was, I would hit it off with him. It was after much coaxing that I agreed. In fact, I took a couple of days telling her I was busy with something or the other. And then I said I couldn’t because I was going away to Islamabad. Good, said Nadi because he was already there and since we were going to be in the same hotel it would be easy.

In the hotel in Islamabad, I called his room and he asked me to come at 3pm because he was seeing journalist Rahimullah Yusufzai an hour later. Though I had read several of Naipaul’s books, in those pre-internet days, I was not acquainted with his face. My knock on his door brought out a short-statured man with a pudgy face and the most remarkably noticeable eyes: they were the saddest eyes I had ever seen.

Nobel laureate V.S. Naipaul died on August 11, 2018. He will be different to different people but the world has undoubtedly lost a great writer

In my estimation, Naipaul was supposed to be hawk-faced — a long, lean face — with fangs for teeth. I looked over his shoulder expecting that person to be in the room. It was empty and I asked very tentatively, “Mr Naipaul?”

“Yes, yes. Please come in.”

We sat down, he at the writing table and me on the sofa, and talked. After 20 minutes, he ordered tea. On the table was a set of very slim notebooks, so slim that they cannot even be called notebooks. At some point in the conversation he started writing in one of those. Then he would go back and ask me about something I had said. I would paraphrase my earlier words, but Naipaul would remind me of my exact words and would ask, “Isn’t that what you said?”

Then he would say, “Thank you. Thank you so much.” The tenderness in this thanks and the touching profundity amazed me. He was not the man I had imagined him to be.

At 3:50pm, I started looking at my watch. If Naipaul was a stickler for punctuality, I was more so. He asked if I was in a hurry and I replied I wasn’t but he had to be away in 10 minutes. He could spare another 15 minutes, he said.

Then he did something astonishing. He said he wanted to read something to me and wanted my impression of the person who was saying it. He added that he would not like to disclose the name because, even in the book he would write, the man was going by another name. He treated me to two pages of his notebook of someone who spoke with a forked tongue.

“Whoever it is, is a liar and a hypocrite!” I blurted out.

It was again the same profound thanks from him. When Naipaul went to the toilet, I sneaked a quick peek at the thin, spidery handwriting and learned which two-faced politician Naipaul had interviewed. On reading Beyond Belief, I at once spotted the man.

In the end as I was leaving, Naipaul asked if I would like to have lunch with him the next day. And so after the meal we came up to his room where he wrote down our conversation in his notebooks. I telephoned Nadi in Lahore and she was astonished to hear I had merited a second meeting. “I told you, you’d get along with him,” she gushed.

What V.S. did not like was hypocrisy and deceit. Truthfulness and being oneself was what he valued and he warmed to such people. It was impossible to impress the man with high-falutin waffle. So many people, in various parts of the world, have discovered this much to their mortification.

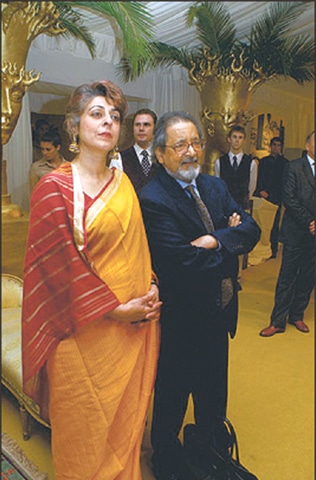

That was all in 1995. Soon he and Nadi wedded and I would get phone calls from them from Britain. Naipaul insisted I must come and stay with them at their country home. I was in Britain in December 1997 and met the couple in their London home in an upper-class part of the city which I now don’t remember.

Two things that stand out from that time. One, after a protracted conversation, V.S. (Vidiadhar Surajprasad) all of a sudden said I should write a novel. His exact words, “You have a novel inside you.” And then he asked me if I wanted to be famous. I replied there was a time I hankered for a name, but now I no longer cared. “Good. You will be well-known,” he said.

Back in Pakistan, a few months later, Shabnam (my wife) and I started to build our house. We had very little money and no idea how we were ever going to complete the project. During one of his phone calls, I told V.S. about our new endeavour. He was full of encouraging words. Months later Nadira told me that he worried very much for us. He feared our project might turn into his own father’s story so touchingly told in A House for Mr Biswas.

Back in Britain in early 2000, I met V.S. and Nadi again in London. At home, our building project was very slowly getting along. V.S. asked me all sorts of questions about it and offered much encouragement. He said when it was completed, he and Nadi would come to stay with us. When he left for his walk, Nadi told me he was very fond of me and she was surprised he had said he would stay with us. “He’s never said such a thing to anyone!”

I forget now if they visited us between January 2001 when we moved into our home and November 2006 when I was again in Britain. But soon after moving, I had either emailed or telephoned them to say we were in our home. When we met in 2006, V.S. was visibly thrilled about our success. On all successive visits to Lahore, V.S. and Nadi always visited. Though they never stayed (their HQ was Nadi’s son Nadir’s place), but they would have a meal with us.

The general impression is that Naipaul was a disagreeable person. Admittedly he rarely smiled and spoke very little. But the V.S. I knew was affectionate and caring. They say he hates India and Muslims even more. As for India, there was a sadness in him for India not being what it could be. If you knew him well enough, you saw the sadness in his eyes; it weighed on him. And though he did not use so many words to voice his grief for India, it was evident. And I know he bore no negative feelings for anyone of any religion.

What V.S. did not like was hypocrisy and deceit. Truthfulness and being oneself was what he valued and he warmed to such people. It was impossible to impress the man with high-falutin waffle. So many people, in various parts of the world, have discovered this much to their mortification. I know one such, an acquaintance of mine, who distributed dozens of photocopies of the review of Beyond Belief published in The Economist. He wanted to be read about. And when the book hit the stalls in Pakistan, humiliation was his lot.

Now at age 85, Vidhiyadhar Surajprasad Naipaul, whose ancestors left India to work as indentured labour in Trinidad, has gone into the great beyond. He will be different to different people, but the world has lost a great writer, and I am bereft of a much-valued friend.

The writer is a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

He tweets @odysseuslahori

Published in Dawn, EOS, August 19th, 2018