The point of stories, one could argue, is to introduce an audience to a character, and make them feel like they know this character, to the extent that they surrender all their sympathies. Stories exist to yank us from our realities by making us fall in love with someone who consumes our consciousness for the duration that we are exposed to them, and occasionally for long after too.

What makes characters come alive is ultimately an enigma — but nobody seems to have captured the alchemy of the process better than the Romantic poet John Keats, in a letter penned in 1817: “when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

I thought of that phrase while watching Sarmad Khoosat’s astounding performance as Prisoner Z, during a 24-hour play conceived by Justice Project Pakistan (JPP) and produced in collaboration with Dawn.com, and streamed live on Facebook, YouTube and on Dawn's website for the entirety of 10th October, which was World Day Against the Death Penalty.

Related: No Time to Sleep demonstrates the power of silence in performance art

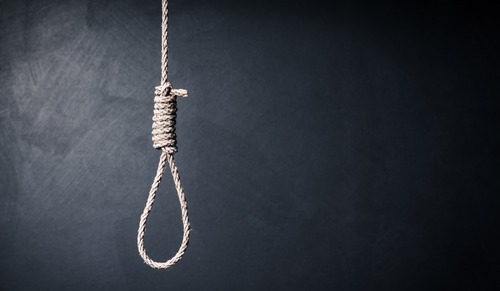

Khoosat didn’t break out of his character for an excruciating length of time, staged to replicate the harrowing final hours prisoners on death row face while waiting to be led to the gallows. He waited in solitary confinement: pacing, trying to sleep on the bare floor, praying, eating, relieving himself, bathing — all before the camera, while a rotating crew of three guards kept watch outside. The only break Prisoner Z received from the monotony of his wait was the heartbreaking scene where his family came to visit to say their goodbyes, his daughters putting their hands through the bars for him to kiss one last time.

Once they left, the seconds slowed to an unbearable crawl. When Z kneels to pray, Khoosat’s back is drenched with sweat. By the time the guards arrived to handcuff Z and lead him to his end, Khoosat himself is gaunt, shivering, stricken. Those final moments were wild — the first time I saw someone acting and truly felt like I was seeing the person they were seeking to portray. The unbroken length of the performance allowed Khoosat to sink into Z’s bones. Without cuts or edits, there was no chance for him to reflect and reevaluate, leaving him isolated in the alternate reality he had been locked into. The cold disbelief of what was coming to him, stirred with the red-hot fear of being unable to stop it, doused with the paralysing thought of the almost-there afterlife: these washed in and out of Khoosat’s eyes without a single flash of betrayal.

Review: No Time To Sleep is an emotionally charged look at capital punishment

Prisoner Z was inspired by the life and death of Zulfiqar Ali Khan, a man who spent 17 years on death row, and completed 33 diploma courses and taught over 50 other prisoners during his time behind bars. His execution was scheduled 22 times.

The detail about him that most remains with me flashed across the screen once Khoosat’s performance wrapped up: Khan received a temporary stay of execution an hour before he was to be hanged. However, another execution warrant was issued a month later, and this time he was hanged three days after being brought back into solitary confinement. Before dying, he asked a guard to tell his lawyers that he felt as though he lived a whole other lifetime in that one extra month. To be so grateful for life — when yours is being taken away from you. I found that infinitely remarkable.

And yet for all the details I have learned about Zulfiqar Ali Khan’s life, the beauty and power of Khoosat’s performance was its universality: by centering on Khan’s pain rather than on the particulars of his life or personality, Khoosat delivered the pain of the many others who also suffered the same fate. In so doing, his performance was exactly what it needed to be: a battle cry against the death penalty in a country that has one of the most broken justice systems on the planet.

At least 496 prisoners have been executed in Pakistan since the moratorium on executions was lifted in 2014, and there are at least 4,688 people currently awaiting execution — based on these numbers, every eighth person executed is killed in Pakistan. From the use of torture to draw confessions, to defence lawyers who fail to gather evidence — prisoners on death row do not receive fair trials, and in certain cases have been acquitted after they are killed. It’s a blood-soaked killing spree playing on repeat and it has to stop.

Read next: Playing the role of a prisoner on death row is an act of solidarity

I was struck by just how many people spoke out against the death penalty, both during the performance and after — several of whom admitted being in favour of it before. To change minds on an issue as divisive as capital punishment is no small feat — and it’s JPP's boldness to dream up a seemingly wild idea but believe in it and follow it through that accomplished this. No Time to Sleep was more than just incredible performance art: it was theatre-fused-with-technology, a brilliant example of persuasive advocacy, a true contemporary epic.

280-character Tweets, 24-hour-long Instagram stories, and Facebook statuses that dissolve into a slew of sponsored posts. Social media, which is too often bite-sized content erupting on speed in real-time, has been accused repeatedly of decreasing our attention spans, taking our focus away from art forms, moments, or conversations that could fuel deeper thinking. And yet, when it came to watching Sarmad Khoosat tick towards the gallows, hundreds tuned in. Not even the flow of cheap, insensitive, misinformed comments flooding the Facebook live stream could pull my attention away from what was happening within the tiny browser through which I watched Khoosat pace in an even tinier box of a cell.

Epics tend to come to us condensed, tailored to the packaging in which they are delivered, hemmed in by the chapter-by-chapter breakdowns set up by their narrators. The genius of No Time to Sleep is that it was an epic tailored perfectly to a new age, an epic that understood the habits of its audience perfectly. It wasn’t a play streamed on Facebook Live, it was a play created for Facebook Live, and it worked better there than it would have in a theatre. It was free for anybody to watch, in the most democratic public space we seem to have in this country. And since everybody has their phones on them all the time, it resolved any and all scheduling conflicts. It was a performance engineered so that everybody could show up — and show up they did.

If it can’t catalyse a big enough turn in public sentiment to lead to a change in policy, then I don’t know what will.

Did you watch No Time to Sleep and would like to share your opinion on the performance? Write to us at blog@dawn.com