Pakistan's debt policy has brought us to the brink. Another five years of the same is unsustainable

Pakistan is facing an economic crisis and the previous governments’ disastrous policies have indebted the country for generations to come.

This has been the rhetoric of the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) government and its senior leadership, including Prime Minister Imran Khan.

And while die-hard PTI supporters, like those of other political parties, blindly believe the rhetoric of their party, some remain on the fence, mainly because the government and its spokespersons have only shared absolute numbers and have failed to present comparative data to cement their claims.

In the absence of conclusive summary data, I had to scour through the documents available on the State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) website, particularly the latest annual report on the state of the country’s economy.

The evidence from this data is conclusive: the last 10 years have seen a continuous and significant deterioration in Pakistan’s debt sustainability, and decades of economic mismanagement bears the blame.

Before jumping into the analysis, a disclaimer on economies and their tendency to borrow. All economies in the world, from the most advanced industrial economies, like the United States and Japan, to those endowed with vast natural resources, like Saudi Arabia and Venezuela, borrow money.

There is nothing wrong with a country floating bonds, financing infrastructure projects through long-term debt instruments, and using capital markets, both domestic and external, to meet its financing needs.

In fact, the PTI will also rely on borrowing during its term, and the absolute value of total debt will certainly continue to increase in the coming months and years.

Related: Why Pakistan will go to the IMF again, and again and again

What is important, however, is for countries to follow a carefully calibrated borrowing policy that minimises the various risks associated with taking on additional debt, such as interest rate and refinancing.

In simple terms, if a country’s policymakers decide to borrow significant sums of money, they better be sure that they can pay back or rollover these loans in the medium- to long-term.

If they fail to take this into account, they find themselves facing economic instability, and may eventually have to go to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Economic analysts, central bankers and government policymakers rely on various indicators to measure risk exposure and debt sustainability. Examples of these indicators are:

- Total government domestic debt as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which essentially shows how much a government owes to domestic creditors as a percentage of the annual output of the economy;

- Total government external debt as a percentage of GDP, which essentially shows how much a government owes to international creditors as a percentage of the annual output of the economy;

- Time to maturity of news loans, which shows how soon the loans must be paid back or refinanced; and

- Whether the loans are on fixed or floating interest rates.

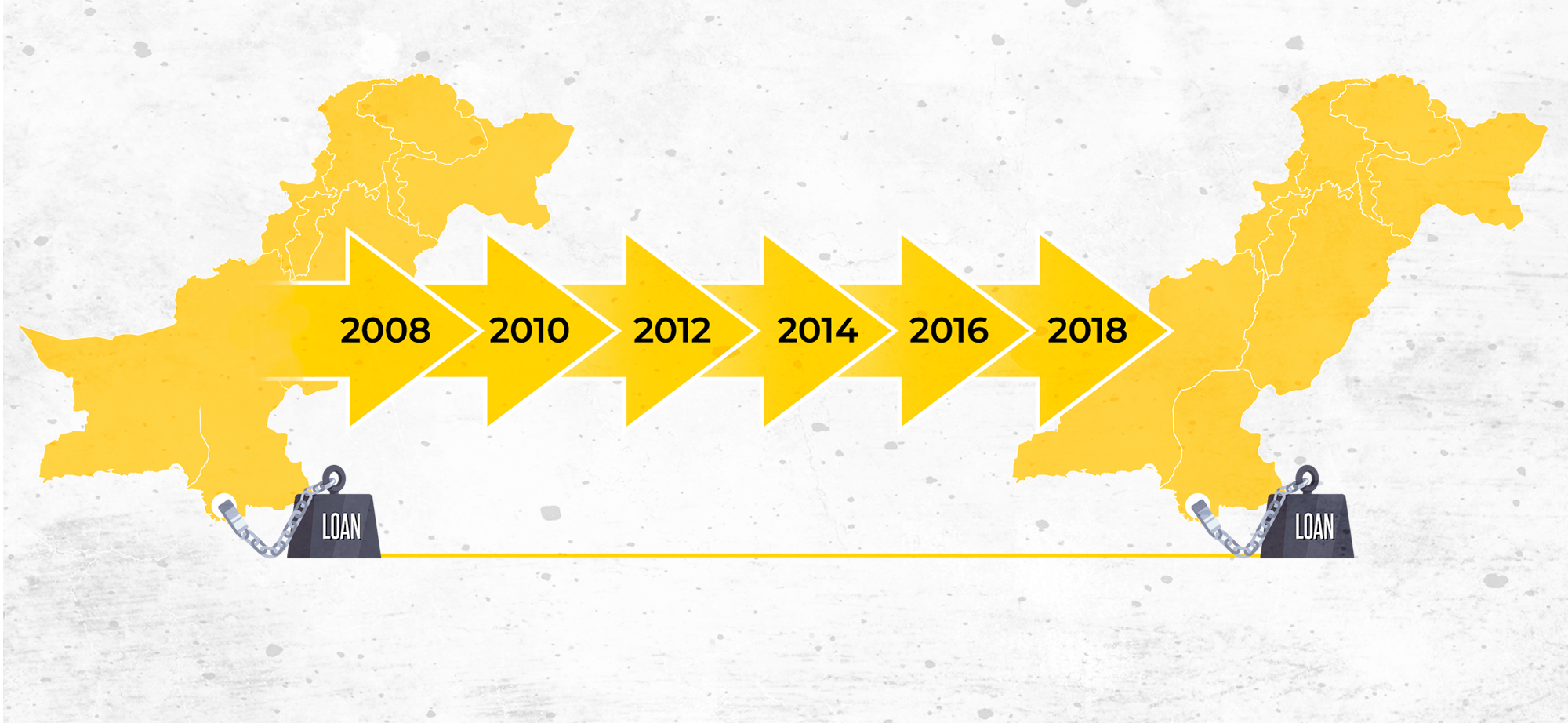

From 2008 to 2018, Pakistan’s position worsened across all these indicators, and little to no effort was made by the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) governments to sustainably deal with the country's addiction to loans and bailouts.

At the same time, it is important to note that the technocrats of the Musharraf era fared no better. In fact, one could argue that they performed even worse, as they failed to take advantage of the economic benefits showered upon Pakistan following 9/11, which included the rescheduling of the Paris Club debt in December, 2001.

By 2007, the country was facing an economic meltdown, and one must view the 2008-2018 period, and the performance of the PPP and the PML-N, within this context.

The PPP era

When the PPP came to power, Pakistan was facing economic, security and political crises all at the same time.

Power shortages were the norm, inflation consistently hovered over 10 per cent per year and oil had crossed $140 in international markets.

Faced with a multi-faceted crisis and lack of domestic resources in the form of taxes — which continues to be an issue today — the PPP entered an IMF programme and began the difficult task of stabilising the economy.

From 2008 to 2013, the total government debt increased by over 135pc, going from Rs6,435 billion to Rs15,096 billion.

As a percentage of the GDP, the total government debt increased by 4.4 percentage points, going from 62.8pc to 67.2pc during this period.

The silver lining was that the PPP’s borrowing policy relied more on domestic than external borrowing.

Much of this had to do with the prevalent economic conditions around the world, where the Great Recession significantly reduced the ability of economies like Pakistan to borrow money from the international bond market.

This meant that the total government external debt increased by only 22pc between 2008 to 2013, going from $42.8 billion to $52.4 billion.

The result was that the GDP growth outpaced the growth in external debt, leading the total external debt to decline from 29.5pc of the GDP to 23.4pc, a reduction of 6.1 percentage points.

The lack of liquidity in the international bond market meant that the PPP relied on domestic borrowing to meet its financing needs.

This led the total government domestic debt to increase from Rs3,412 billion in 2008 to Rs9,833 billion in 2013, a jump of 188pc.

The total government domestic debt went from 33.3pc of the GDP in 2008 to 43.8pc in 2013, an increase of 10.5 percentage points.

In its 2012-13 annual report on the state of the economy, the SBP stated that “Pakistan’s public debt continued to be a major risk to the country’s macroeconomic stability” and that “concerns about debt sustainability deepened with the growing burden of debt servicing”.

By 2013, domestic debt represented two-thirds of Pakistan’s total government debt, which entailed “significant risks to Pakistan’s fiscal and debt outlook”, according to the SBP.

This “implied less fiscal space for development spending” as “overall interest payments” had outstripped tax revenues.

The PPP had over-relied on short-term domestic debt to meet its financing needs, and the SBP noted that “re-pricing of this debt at higher interest rates” will add to the country’s debt servicing burden.

The SBP concluded that “Pakistan is effectively in a debt-deficit spiral” and, unlike the 2000 crisis, which led to a comprehensive restructuring of the country’s Paris Club debt, the challenge was “now with Pakistan’s domestic debt”.

The PML-N era

It was under this crisis that the PML-N took over the reins of the economy in 2013 and, much like the PPP, it had to seek a bailout from the IMF soon after coming to power.

But while growth returned, and some issues were solved, the PML-N also failed to effectively deal with Pakistan’s debt crisis.

It faced issues like those faced by the PPP: chronic power shortages, lack of sufficient financial resources, oil prices that remained high at over $100 a barrel and the rate of inflation hovering around 10pc per year.

Two things, however, worked greatly in its favour later: by 2015, international oil prices had fallen dramatically, going below $50 a barrel.

Secondly, at that time, the world was awash in liquidity as record-low interest rates and quantitative easing (essentially the printing of money) in the US, Europe and Japan led to a reach for yield in the international bond market. This meant that countries like Pakistan could borrow money at low interest rates.

From 2013 to 2018, the total government debt had increased by another 79pc to Rs26,968 billion.

The total debt as a percentage of the GDP in this period increased by 11.2 percentage points, going from 67.2pc of the GDP to 78.4pc.

A significant contributor to this increased reliance on debt was the PML-N’s focus on large infrastructure projects, including many sorely needed in the power sector.

In addition, the massive rollout of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which led to further inflows of external loans, led the total government external debt to increase by 46pc to $76.3 billion by 2018.

This borrowing outpaced GDP growth, leading the total government external debt to increase to 27.6pc of the GDP, a 4.2 percentage point increase from 2013.

The PML-N’s appetite for debt was not satiated by foreign debt alone, and the government continued to rely on domestic debt as well, with the total government domestic debt increasing by 78pc to Rs17,483 billion by 2018.

As a percentage of the GDP, the total government domestic debt increased by 7.1 percentage points to 50.8pc of the GDP.

Debt, taxes and inflation: Highlights from the last 10 years of Pakistan's economy

What is also significant to point out here is the situation of public-sector enterprises (PSE), particularly their domestic debt profile.

While PSE’s domestic debt increased from Rs137 billion in 2008 to Rs312 billion in 2013, an increase of 128pc, the period of 2013 to 2018 saw an increase of 242pc, with PSE’s domestic debt reaching Rs1,068 billion.

The PPP, which had kept PSE’s domestic debt stable — it increased from 1.3pc to 1.4pc of the GDP — PSE’s domestic debt climbed to 3.1pc of the GDP by end of PML-N’s term.

A major driver of this was the increased power generation in the country, which occurred without significant structural reforms in the energy sector.

This meant that circular debt — PSE liabilities — continued to rise at an accelerating rate as more energy was produced after the successful completion of power projects.

The SBP’s 2017-18 annual report’s chapter on domestic and external debt sounds eerily familiar to the 2012-13 chapter on the same

Macroeconomic imbalances and a twin current and fiscal account deficit, according to the SBP, “quickened the pace of debt accumulation.”

While the 2012-13 report warned that the short-term nature of domestic debt had raised interest rate risks, the 2017-18 report pointed out that the newly issued external loans are on floating interest rates, which “may pose challenges for future debt servicing” as global interest rates rise.

Explore: What Pakistan can learn about tax reforms from developing countries

Much like the PML-N in 2013 and the PPP in 2008, the PTI has inherited an economic crisis. Its economic team must stabilise the economy under an IMF programme and, simultaneously, rollover existing external debt at a time when global interest rates are rising.

This will be a mountain to climb, especially as the average maturity of the newly issued external debt, which hovered around 20 years in 2013, was halved to almost 10 years during the PML-N government.

So what’s wrong with borrowing?

Opposition leaders, mostly those belonging to the PML-N, have argued that there is nothing inherently wrong with countries borrowing.

As mentioned earlier, this is true, but comparing Pakistan’s debt profile with a comparable country like Bangladesh shows that Pakistan is addicted to debt and that the economy cannot sustain the practice.

Bangladesh is an apt comparison because it has a shared history with Pakistan and was, in fact, less developed than the latter when it emerged as an independent nation.

Furthermore, its political economy has similar issues — a history of coups, an assertive judiciary and a low tax base.

According to the IMF, the total public and publicly-guaranteed debt in Bangladesh stood at $35 billion in 2017, which is 14.3pc of the country’s GDP.

At that same time, the country’s public sector domestic debt stood at about 18.9pc of the GDP, according to the IMF.

This means that, unlike Pakistan, the risks of “external debt distress and overall debt distress remains low” in Bangladesh. This is at a time when Bangladesh’s GDP growth has outpaced Pakistan’s and stands at 7.3pc.

Check out: Puranay problems that Naya Pakistan has to deal with

My article is not a comparative analysis of Pakistan’s and Bangladesh’s economies, but one must wonder how is it possible for two similar countries to have such divergent paths.

Suffice to say that Bangladesh has been successful at developing a globally competitive export sector and these earnings, coupled with a high remittance inflow, have allowed the country to rely considerably less on borrowing to meet its financing needs.

There is a lot of truth to the PTI rhetoric; however, it must now move beyond campaigning and get down to business.

The challenges faced by Imran Khan and his finance minister, Asad Umar, are tall but the PTI signed up to be the party of change and reform. The economy is ripe for reform.

Critics may say that these debt statistics will be even higher by the time the PTI completes its term, and that may very well be true.

Pakistan’s borrowing policy over the last decade has brought the country to the brink; another five years of business as usual, where debt continues to pile up, cannot be sustained.

What the PTI does remains to be seen, but what is true is that it has been dealt a tough hand, and Pakistan cannot afford to see the party fail.

Are you a researcher or policy analyst focusing on economic reforms? Share your insights with us at blog@dawn.com