HAS the power hierarchy in Pakistan changed while we weren’t looking? Blink, and you’ve missed it.

According to conventional wisdom, power flowed from the barrel of the gun, with the army masters of all they surveyed. Then came the judiciary, which, over the last decade, became hyper-active with its massive overuse of suo motu powers. The political class came a distant third. Sundry law-enforcement agencies figure in there somewhere, but are distinctly subservient to the institutions higher up the pecking order.

Read: Do we have what it takes?

While the military still calls the shots, it seems to have run into a brick wall in the form of the Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP), the ultra-extremist outfit that recently brought the country to a standstill for three days without let or hindrance from the state. For anybody to openly preach mutiny against the army chief without prompt action from Pakistan’s most powerful and respected institution is unprecedented. It is also a sign of weakness, and signals a shift in the country’s power dynamics.

For anybody to preach mutiny without prompt action by the state is unprecedented.

And what about the judiciary? After all, it was the Supreme Court’s honourable decision to free the unfortunate Aasia Bibi from an absurd blasphemy accusation which has ruined her life that brought thousands of TLP supporters out on the streets. But when the leaders of the TLP announced that the three judges who had declared her innocent should be murdered, there wasn’t much noise from the Supreme Court. And mind you, this is the same institution that has repeatedly come down very hard on politicians for contempt of court.

As for politicians, we have the odd — but predictable — spectacle of Prime Minister Imran Khan promising to confront the rioters with the might of the state, only to beat a swift retreat and sign an ‘agreement’ that was more of an article of surrender by a subservient authority. This should surprise nobody who has followed the trajectory of Khan’s rise to power. He has never made a secret of his sympathy for religious extremists: not for nothing is his nickname Taliban Khan.

The MQM learned a quarter of a century ago that the power to shut down Karachi at will gave it immunity from reprisals from the state. With its hands on the country’s jugular, it could run riot with impunity, collect protection money and generally hold Pakistan’s richest city to ransom. From a student organisation to a political party with a hardened militant wing, the MQM ruled Karachi unchallenged for decades. The operation in Karachi during Benazir Bhutto’s second government in the mid ’90s did little to stop them.

Imran Khan then discovered that by laying siege to Islamabad, he could command the state to do his bidding. Thus his repeated dharnas and threats of sit-ins were highly effective in sending basically political issues to the Supreme Court. We all know the outcome of our judiciary’s decision to intervene.

The TLP tested this model by weaponising the blasphemy law at its damaging sit-in at Faizabad, severely disrupting traffic between Islamabad and Rawalpindi for a fortnight. Instead of being thrown in jail, the participants were given cash awards by a serving general. In addition, their demand for the resignation of Zahid Hamid, the law minister in the PML-N government, was accepted. So much, then, for the writ of the state.

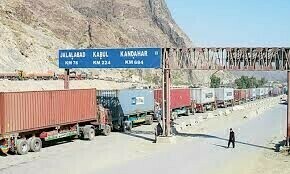

And if the dharna formula worked in Islamabad, how much more effective would it be when applied across the country? We found out the hard way recently when hordes of TLP supporters blocked roads across the country, bringing factories, schools and offices to a grinding halt. Cars, buses and trucks were torched, and billions lost in three days of anarchy. But who’s counting the cost when it comes to religious fervour?

Apart from the losses to the economy and to innocent people caught up in the madness, state institutions have suffered a massive hit to their reputations. The army is no longer unassailable. The judiciary’s power to punish contempt is now seen as highly selective. And Imran Khan has been exposed as a paper tiger, who growls a mean growl but, when push comes to shove, caves in to extremists.

While we discuss the fallout from the TLP riots, spare a thought for poor Aasia Bibi, the innocent target of Khadim Hussain Rizvi’s demand for execution for a crime she didn’t commit. Although the government in its craven surrender document agreed to place her on the Exit Control List, the fact is that she cannot legally be prevented from leaving the country as she has not been found guilty of any crime.

And if Salman Taseer, a Punjab governor, could be assassinated by a member of his police security team, who can guarantee that a similar fate does not await her at whatever “safe place in Pakistan” she is being kept? The fanaticism infecting the country is not limited to just a handful of zealots.

Published in Dawn, November 10th, 2018