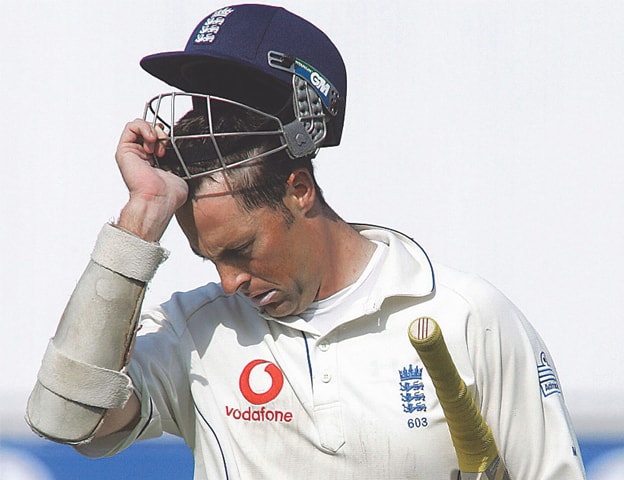

When Faisal Iqbal got under Marcus Trescothick’s skin in the Oval Test in 2006, he was, perhaps, emulating one of the mind games that his uncle — Javed Miandad — used to play. But at the time, no one, including Faisal, had a clue that Trescothick was fighting a battle with an inner demon — depression.

Trescothick’s frailty was evident when he lost his cool and, in turn, hurled abuses back at Faisal who was standing at forward short leg. One delivery later he hit the ball straight into the hands of Mohammad Hafeez at the point region and got out.

It must have been more than ‘gamesmanship’ for Trescothick. A few months down the road he had to pull out of England’s Ashes tour due to depression. He was perhaps the first renowned international cricketer of the new millennium who openly discussed the dark side of his life — depression — in his autobiography Coming Back to Me.

Depression is a serious illness. A sizeable number of cricketers suffer from it too. It’s time people around them, and they themselves, talked about it before it gets too late

Most of us would have thought that ‘pressure’ in international men’s cricket is so immense that it can mentally break some of the players. But then England women cricket team’s wicketkeeper Sarah Taylor shared her issues in public, which somewhat changed the common perception that the men’s game was more ‘competitive.’

Now the question is: depression plaguing cricketers hailing from ‘western’ nations only? One has hardly heard any stories about cricketers from the subcontinent, West Indies or South Africa who may have gone through this terrible mental turmoil.

Not many people remember that, in 1982, amid clandestine arrangements to sign cricket contracts, a 14-member Sri Lankan ‘rebel’ team toured South Africa. At the time, the 24-year-old Anura Ranasinghe was also a member of that team. But after returning home he just couldn’t cope with the consequences of that rebel tour and suffered depression. He resorted to drinking as a crutch for his mental problems. He died in his sleep in 1998. He was 42.

Max Babri, a renowned sports psychologist in Pakistan, who has worked with the Pakistan cricket squad which won the 2009 World T20 Championship and was part of the Pakistan cricket team which toured India in 2013, says that depression is a state of mind and it happens to everyone including cricketers. “Everyone goes into depression and it is a feeling when one is low and thinking that I may not be able to achieve what I want to achieve in life that the future looks a little darker. Sometimes it comes from early childhood programming where a child has gone through frequent unnecessary scolding.”

Many would argue that if you are religious or spiritual then you’re at a lower risk of suffering from depression. Most cricketers from the subcontinent practise religion staunchly and they strongly believe in spirituality, which may give us an impression that it works. This argument is quite valid to a certain extent. But then what about the common people who also live in the countries of this region? Don’t they practise religion? Are they also immune to depression? Of course, not! And cricketers are no exception. After all, it is an illness at the end of the day.

Babri has an interesting take on this. He says, “Some cricketers become so superstitious about their religious rituals that, in case of not living up to expectations, they feel as though they deserve to be punished and will be unsuccessful in the middle [ground]. Interestingly, it works the other way round for a person who is not religious.”

According to the World Population Review, there are 2.1 suicides happening per 100,000 people in Pakistan. In September 2018, a 24-year-old fashion model in Lahore hanged herself because she lost the battle against depression. A couple of days later, a college student in Peshawar took his life after attaining low academic grades. That said, in a country which has produced 234 Test and 218 ODI cricketers, there is not a single example of an international cricketer coming out into the open with any mental issues, which is surprising to say the least.

The only incident which was relevant to some degree was of wicketkeeper Zulqarnain Haider, who was part of the team which embarked on the infamous tour of England in 2010. Later that year, he went missing during the ODI series against South Africa in the UAE. Apparently he left the team due to life threats, but a few days later the team manager Intikhab Alam said, “I am not an expert to say this but if I look at his behaviour in the wake of this incident, I feel he had some mental problem. Even the players feel the same way.”

So, do Pakistan cricketers face depression?

Babri says they do. “Yes, the problem [depression] exists in both Pakistan men and women’s teams. I’ve also mental coached the women’s cricket team in the past. In my experience, girls are more prone to depression because they are far more emotional and they face more frequent emotional ups and downs than boys,” he says.

He adds: “At times players feel that, if they don’t perform, they might get dropped from the team. A player is always under enormous pressure, even more when they get into the riches. They have to look into their expenditures. In some cases their family members stop earning because they have a ‘hero’ at home to fall back on. Players feel depressed when they have to deal with such pressure. Consequently, in such a situation, a cricketer could become more tempted to venture into the grey areas for monetary benefits.”

In Babri’s opinion, depression can make a cricketer selfish. “If a cricketer’s performance is not up to the mark, he or she may feel a little down. And when a cricketer feels down he or she becomes less of a team player and focuses more on individual performances.”

In February 2018, Amir Hanif, a cricketer who represented Pakistan in five ODIs in the 1990s, lost his 18-year-old son Mohammad Zaryab. Zaryab committed suicide after getting dropped from an under-19 team. After facing this huge tragedy, Hanif said at a press conference that his son was feeling pressurised. “He was told he was overage. The coaches’ behaviour towards him forced him to kill himself. We should take steps to save others’ sons.”

In a country such as Pakistan, where nepotism easily overshadows merit and players often get dropped from teams due to reasons other than their performance, no one would’ve thought of such a tragic outcome. Perhaps Zaryab was in need of help, a shoulder to cry on, but sadly no ‘messiah’ came to save him. A simple ‘pep talk’ may have saved his life.

“Issues related to depression are quite common in the subcontinent. Basically it is also a matter of awareness. People here generally don’t talk about these things and tend to suppress their feelings, whereas in the western world they are more open about discussing such issues,” Babri points out.

Perhaps talking about one’s mental health is still a big stigma here as we bury our heads in the sand. But in today’s fast and highly competitive world of cricket, let’s start talking about it before it gets too late.

The writer tweets @CaughtAtPoint

Published in Dawn, EOS, December 2nd, 2018

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.