Iran: Passionate and opinionated — and laced with humour and a lust for life

Iran stands at a unique junction of tourism today. Despite the advent of social media and a truly global trade, this country invokes a mixed set of emotions outside its borders.

For me, it was almost liberating not to have textbook images or holiday brochure promo material to raise expectations — and the inevitable disappointment when it doesn’t materialise.

A lack of media exposure made me realise how little of daily Iranian life is known to outsiders, and how rare it is to be able to arrive in a country with the sensation of an utterly blank canvas waiting to be filled.

Tehran

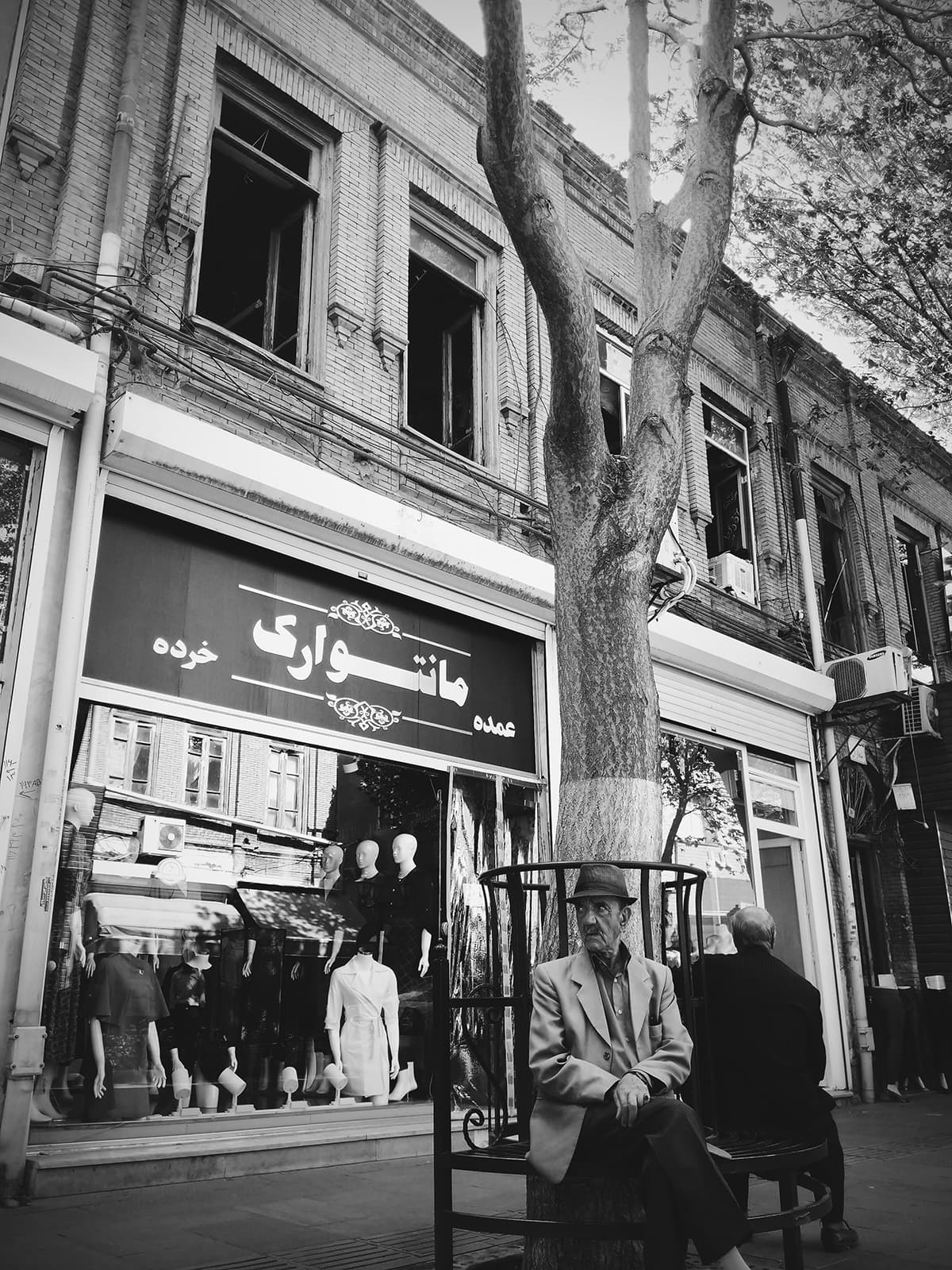

My journey into Iran started with Tehran; recently dubbed as “LA with minarets” albeit many third-world clichés and misconceptions.

As I skimmed the heavy streets, Tehran began to take shape, transforming itself from the howling mess of concrete and metal into a city with distinct custom, character and charm.

Orientation was easy, with the dry mountains dominating the northern skyline — something relatable to the capital back home — and to the west, the Milad Tower rising amidst mild chaos.

Over time, it became evident that Tehran was a divided city, not just physically through Valiasr Street, but by something less tangible.

The north is home to the wealthy and the Westernised, whereas the south is rundown where the poor, and by default, perhaps the pious reside.

The divide in wealth also brings in the various shades of infatuation with Western brands, the fashion sense and glitz Tehranis are known for.

But the defining feature of Tehran, the anarchic traffic and the smog, do not discriminate based on wealth or social boundaries. In the city centre, the two distinct worlds merge in a whirl of commerce and feverish activity amongst a mishmash of majestic old buildings and shabby concrete decay.

As you walk around the city, there’s a sense of pre- and post-Revolution inertia advent in architecture and, more evidently, in the city’s street names.

After the Revolution, most roads in major cities were renamed with a sense of anti-Western fervour, changing the likes of Eisenhower Avenue to Azadi Avenue, and Shah Raza Square to Enqelab Square.

The consciousness of a new identity inculcates the Islamic regime, much like the new wave of Islamisation in Pakistan with renamed roads and junctions in Lahore, for instance.

Reminiscing about my life in Lahore and its rather deteriorating gardens, gardens in Tehran are a triumph of ingenuity and design, oases of tranquility that provide much needed respite from the chaos of the bustling streets and the blistering summer sun.

My time in Tehran, however, was short and slowly coming to an end. I felt a twinge of sadness about leaving Tehran. I had become strangely fond of the city, with its layer upon layer of intrigue, double dealing and whispered stories — the people and the buildings revealing their own histories.

It was grimy, raucous and chaotic at times, but it was also subversive, creative and truly alive, a testament to human ingenuity and the Iranian spirit — almost rebellious at times.

Tabriz

As I took the train to Tabriz from Tehran, gazing at my new world, I realised I had very little sense of what Iran would look like from a day-to-day travelling point of view.

This northwestern corner of Iran, the province of Azerbaijan, was mountainous but dry and hot, its faraway hills hazy and barren.

As the Farsi signs, shop names and adverts flashed past me, I was overcome with a rush of excitement followed by dread of the unknown. I was slowly moving from the Farsi-speaking area of Iran into the Turkish-speaking zone — somehow becoming even more foreign in an already foreign land.

Once in the historic city of Tabriz, as if passing into a parallel universe, I found myself in a maze of winding walkways, walking on uneven cobble worn from centuries of trade along the Silk Route.

Each turn under the vaulted ceiling was a turn of page in the history books. When the Europeans discovered new sea routes to China and the once-thriving Silk Route lost its lustre, Tabriz Bazaar adapted and lived on.

Today, unlike the grand bazaars of Istanbul and the souks of Marrakech, this bazaar was not geared to tourists but was truly the one-stop shop where Tabriz residents dropped in for their daily needs, from fruit to tea to socks to underwear.

It felt like I was the only outsider roaming aimlessly and looking for a piece of my own history. Lo and behold — I walked right into it — a stall of Pakistani mangoes. It suddenly felt like home again.

After a couple of days in Tabriz, I awoke on the morning of departure with the twitchy anticipation familiar at the start of a long journey.

Despite feeling as if I had already seen the world just in the past few days, the entire country lay ahead of me — waiting to be explored.

The next leg of my journey was towards the Caspian Sea and then tracing along the coast back to Tehran. I still had more than 2,000 kilometres of territory to discover.

Caspian Sea

The formidable Alborz Mountains divide the sea and the central plateau, stretching all the way from Armenia and Azerbaijan in the north to Afghanistan in the east.

Moving southwards along the coast from Astara towards Ramsar, I came to upon Rasht — a city with a quintessential European vibe owing to the trade between the Caucasus and Russia.

For the entire stretch of the coast, no ferries ran across the border into Azerbaijan, and the beaches were mostly empty, save for a few lonely fishermen whose dilapidated shacks and boats demonstrated how Iran’s caviar industry, once a flourishing export, had become a casualty of both international sanctions and uncontrolled fishing.

After exploring the coast, I was heading back to Tehran, turning south from the Caspian and back over the mountains, touching the northern fringes of the salt desert, Dasht-e-Kavir, before entering the capital again.

My travel along the coast and at the peripheries of smaller cities gradually revealed a grim reality about the current political and religious ethos of the country as well.

At major junctions, it was a common sight to have two towering Ayatollahs stare down at you from a huge billboard with large Iranian flags lining the main route, fluttering green, white and red in the breeze.

I wondered how long it would take for me to get used to these two men seemingly monitoring my every move — a metaphor about life in Iran as well, especially for women.

I had travelled in many other countries where leaders ensured they loomed large in daily life, but I had never witnessed a cult of personality employed on this scale and frequency.

Isfahan

Passing through Tehran and on to Isfahan provided the desert roadtrip I had been dreaming of: open plains of parched brown with nothing but the faint shapes of distant mountains breaking up the horizon.

It was a liberation of sorts from the usual business of life, and simply — just stuff.

Peeling off from the highway, I wondered if I was ready for the onslaught of another Iranian city, but it’s almost impossible to not be charmed by the city upon arrival.

Nuclear experimentation aside, and if you ignore the thundering steel industry on its outskirts, this is Iran’s “pretty city” — former capital of the Safavid Empire of the 16th and 17th centuries — a high point for Iranian art and architecture.

Although its political power has waned over the years, Isfahan continues to live as Iran’s glittering jewel. Despite the city’s almost film-set like appearance, the city doesn’t seem to provoke the love and devotion in Iranians one might imagine.

In other cities, I was warned about Isfahan’s jingoistic leanings and the wily ways of its people. It’s a tourist hub, and like all cities that rely on tourism, one has to be a skeptic at heart. As for most travels, people and art stand separated.

At Naqsh-e-Jahan, the golden domes caught the late afternoon sun, intricate patterned tiles of yellow birds, pink flowers and classic Persian blue geometric designs decorated every building, and in the warm breeze the fronds of palm trees swayed, casting long shadows across the streets.

The city was living up to its hype.

Kurdistan

Leaving behind Isfahan’s glistening centre, its western outskirts could have belonged to any modern Iranian city — featuring as they did the usual sight of oily car repair shops, light industry and cinder block mosques under construction.

Ahead of me, the land turned rugged. The Zagros range appeared in distant layers of brown, purple and grey. The road slowly emptied and the air cleaned.

As I meandered through the rugged range, houses began to appear crumbling, newly-built block walls often wonky, and while the tarmac extended along the main highways, the side streets of the villages were just dirt tracks.

Animals and children grubbed around in the dust and fires burned at either the side of the road, where old women in chadors boiled enormous blackened kettles of water for tea — a common sight.

A few kilometres ahead, before approaching a shanty town, I came across roundabouts mixed with the moralising billboards and aggressive military murals, these examples of state-sponsored art epitomised Iran’s complex and contradictory worldview, as if the combative and the cute, the somber and the absurd could all coexist without conflict.

There were giant billboards of the Ayatollahs but there were also women sitting underneath them and enjoying the evening cup of chai.

Further north were the Lurs and north again were the Kurds, with their own province of Kurdistan.

The general attitude of the tribal groups in Iran seemed to be positive; people spoke of them as gentle, noble people, the only exception being the Kurds, who seemed to be viewed as troublemakers, but that too dependent on what end of the political spectrum one talks to.

An independent state of Kurdistan had been promised when the Ottoman Empire had broken up after the First World War, but never materialised and when the land was carved up, the Kurds ended up straddling the borders of Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey.

Their fight for independence, although not as strident in Iran as in Turkey or Iraq, has never gone away.

Despite their political struggles, the Kurds came across as, by far, the most hospitable people I met in Iran. Since tourism in this region is scant, the general curiosity of the people is evident from their willingness to speak English with every foreigner.

The mountainous region in Kurdistan gave birth to interesting architecture, too. Along the main route, one would come across small villages of flat-roofed blocky little mud-brown houses, nestled in the foothills and dwarfed by the mountains that loomed behind them.

But the deeper into the mountains I went, the sparser the land and the less frequent the signs of civilisation became until, after climbing for several miles, I was alone under a vast sky in a widescreen panorama.

This urge to hide away for a while was an almost primal need for shelter; I recognised it from my previous journeys and I knew it was a temporary craving.

It was simply a response to always moving on and being outdoors day in and day out, weathering the elements and a continually changing environment, forever in the company of strangers, assessing and constantly making decisions, every minute of every day.

There was no chance of being pestered here. I was the only guest at the hotel in Sanandaj, and it sure seemed they weren’t expecting any others. Kurdistan was a break that my mind and soul needed.

Yazd

It was now time to move on to another dry region of Iran, but this time, in stark contrast to Kurdistan.

The highway was long and dreary, but upon entering the southern desert, the road took a majestic turn as it approached Yazd, emerging on to a scene reminiscent of the American West.

Flat scrub transformed into high desert, with mountains on the horizon and great towers of rock in stripes of red, yellow and golden brown lining the route.

The hangover from Kurdish hospitality was still looming in my mind and the new Yazdi terrain was enamouring. It also kept me thinking about Pakistan.

The two countries had far more similarities than either would care to admit; both maligned and misunderstood, tarnished in the eyes of the world by a minority of religious fundamentalists and rowdy politicians, but in truth, populated by generous, hospitable people.

Yazd came as a blessed relief. Despite being cursed with the usual Iranian traffic on the outskirts, its centre oozed antique charm and the timeless tranquility of an ancient desert citadel.

I was in awe as I walked around the mud-walled old town with its winding alleys and adobe-type houses with their domed roofs and ornate wood doors.

In Yazd, there was a tangible feeling of being in one of the oldest cities in the world. Iranian ingenuity was visible at every turn, from the qanats, underground water channels, to the badgirs — the square brick wind towers that make up Yazd’s unique skyline.

These are amongst the most striking feature of the city and a source of great pride to the Yazdis. The Dowlat Abad Garden boasts the highest badgir in all of Iran.

At the Amir Chakhmaq Square and its mosque, among the promenading families and groups of boys messing about on sun-bleached mopeds, there were several men dressed altogether differently from anyone visible in Iran, bearded and sandalled, wearing flowing white shalwar kameez.

These were Baloch, who bring a plethora of goods from Pakistan and subsequently the Iranian province of Sistan and Baluchestan. The fusion of two countries sharing a similar province was most evident here.

Shiraz

My last stop in Iran was the city of Shiraz. Rolling down the steep, sweeping descent towards the city, Shiraz appears as a city full of promise.

A jumble of the ancient and the new, dusty brown blocky homes, modern high rise hotels and offices, 1960s tower blocks, domes, minarets and flyovers all nestled together in the rocky folds of the surrounding hills and dotted with bursts of green parks and trees bringing life to the arid cityscape.

It’s akin to San Francisco, a hip city of rebels, lovers and poets, founded on the passionate words of Hafez and Sa’adi on the tradition of wine and rowdy taverns and compounding its reputation with protests.

The city certainly felt livelier, louder and tattier than Isfahan with its refined boulevards, or Yazd with its tranquil antique alleyways. This was a working, moving, living city.

While I was walking the streets, people said it was like this every night, that Shirazis liked to get out and enjoy themselves, this is what they live for here.

Restaurants were full, shops still buzzing after dark and, of course, picnickers making the most of every patch of grass there was.

The poet Hafez enjoys a divine reputation here, with his significance expounded in the everyday lives of Iranians. His name and poetry cropped up everywhere along my journey: on tiles, buildings, rundown hotels, and his magnum opus, Divan-e-Hafiz, was found at every household.

His poems epitomise the Iranian mindset: passionate and opinionated but laced with humour and a lust for life.

His moral and religious messages elevated him to oracle status, but they sat comfortably alongside admissions of human frailty and decadence, including plentiful references to desire, wine, and drunkenness — a constant state of flirtation with the current regime and its doctrine.

Hafez’s world was a harmonious blend of the mystical and the human, as if no conflict existed between the two. His writing is celebrated each night at the tomb, with continuous renditions of his work played at a mild volume on speakers throughout the complex.

A perfect ode to Iran and its people — a country with conflicting identities.

Have you travelled alone abroad? Share your experience with us at prism@dawn.com