Like Allama Muhammad Iqbal, Iftikhar Arif has enjoyed the privilege of drinking from both wells: eastern and western. And just like Iqbal, he did not allow himself to be overwhelmed by the ideologies of the West. This is a fact that has been noticed by many of his commentators, who include the bigwigs of literature such as Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Parveen Shakir, Mumtaz Mufti, Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi, Syed Zameer Jafri, Annemarie Schimmel, Intizar Husain and others. However, scholarship on Arif’s poetry has mainly focused on issues of identity, chaos, religion, migration, romanticism and spiritualism. Critics — for example, Abdul Aziz Sahir in Iftikhar Arif: Fun Aur Shakhsiat [Iftikhar Arif: Art and Personality] — have also studied his craft and explored the way he employs the metaphors of chiragh [lamp], kitaab [book], khwaab [dream], khaak [dust] and ghar [home].

Arif’s poetry offers far more than what critics have so far been able to see. How do his birds and trees teach us about eco-consciousness? How is the loneliness of his narrators helpful in understanding the psychosocial issues of the postmodern human? What does the metonymy of titli [butterfly] mean? How does his employment of a religious framework in his poetry help him venture through difficult terrains? How does his poetry respond to oppressive rules, international aggressions and exploitative economic systems? People with these and other similar questions will find answers through a very careful reading of his poetry, but the question that intrigues me the most is this: sailing through waters of all kinds, how does Arif anchor his poetry in the oceanfront of resistance?

Even a quick reading of his poetry shows that Arif harbours lines of resistance through a very skilful representation of silencing. Even when the poet does not speak, when he leaves gaps and aporias, those silences are considered a meaningful form of resistance. After all, how can the silence of eloquence not be registered? A careful reading of his poems shows that Arif’s theorisation of silence is patterned in sophisticated stages.

Silence can also be eloquent and have its own lifecycles in poetry

The first stage in this pattern is when silencing is wanted and woven by those who loathe voice. For instance, in ‘Khauf Ke Mausam Mein Likhee Gaee Aik Nazm’ [A Poem Written in the Season of Fear], we see how hunters — who are as blind as their consciences — want to keep brightly chirping branches silent. These hunters of voices want to encage them to avoid the threat they may pose to their sleeping consciences. This is clearly the birth of the idea of silencing in the mind of the oppressors, and Arif readily notes it:

[A hunter, blind as his conscience is blind/ He takes no stock of times of sanctuary/ His aim unfailing, he aspires/ To still the singing voices on the radiant boughs/ Aspires to open every path to tyranny] (Translated by Ralph Russell)

The second stage in the process is when the oppressors launch the project of silencing and are actually able to silence some of those who raise their voice. Arif shows the pain this stage brings with it by turning our attention to those who could come to the rescue of the silenced ones, but voluntarily stay silent. ‘Aur Hawa Chup Rahi’ [And the Wind Kept Mum] is a commentary on this sort of volunteering. This poem depicts stillness enforced so successfully by the political condition that we arrive in a time-space that has quiet all over it. Doves have been displaced, birds robbed of their wings, pastures trampled. The land is plagued. And when all of this was happening, the powerful wind remained indifferent.

The next stage leads us to a conceptualisation of the oppressors. In this connection, ‘Abul Haul Ke Betay’ [Sons of a Pharaoh] is a poetic verdict that those who forcibly take over are simply the pharaohs of the age. Their presence alone is proof that all those who are upright should not be tolerated anymore. However, instead of negotiating with the pharaoh of the time, the poet opts for an eternal exit.

In ‘Aik Rukh’ [A Perspective] Arif theorises sannaata [utter silence] in a unique way. Downplaying all the tools of control and cruelty, he shows that all the hues and cries of the oppressor are always followed by a command of silence. This silence, he believes, is a voiced silence. It eats up all the noise of the war drums, and registers its protest in a remarkable way:

[And every time the aftermath — a realm of total silence/ A silence that swallows the terror and horror of victorious drumming/ The pomp and show of the standards/ Silence is that rhythm of defiance, a form of protest] (Translated by Brenda Walker)

Now, this is heroising of the silence of testing times. Because when ruthlessness expects everyone to sing odes to it, those practising a strategic silence are actually voicing their disdain for them.

‘Aik Rukh’ helps us to read the irony packed in another poem by Arif called ‘Aakhri Aadmi Ka Rajz’ (The Last Man’s Boast), in which all the courtiers and collaborators of the king are satisfied after doing away

with all their unbowed citizens. They see peace in hanging all the heads that refused to bow. This, of course, is a critique of the shortsightedness of the courtiers of a king, and this critique is, without doubt, timeless in its appeal and relevance.

At another stage, reawakening begins with a whisper of dislike for silence. The poem ‘Sargoshi’ [Whisper] is an attempt to convert despair into hope. While it admits that the times are wrong and the realities are bitter, the whisper attempts to induce hope and teach courage to a soul that has completely given up.

Next to it is the birth of a desire in the heart of the poet. ‘Pata Nahi Kiyun’ [I Don’t Know Why] sees this age as a sea of tears and a forest of arrows and, strangely, the poet wants this apparatus of silencing to pierce only his eyes and heart! He wants everyone else to be spared. This desire for himself taking all the blame, and being at the receiving end of the stone-throwing people, is also reflected in Arif’s poem ‘Scandal’.

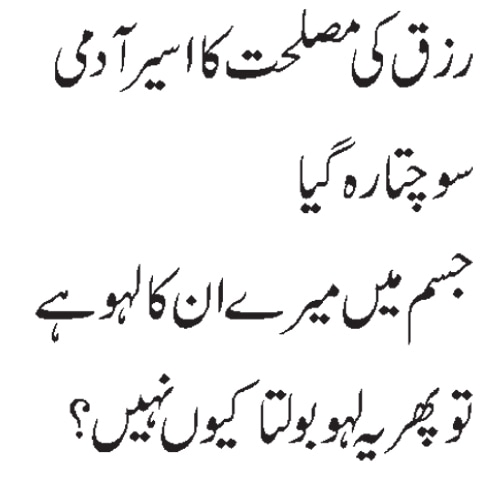

This desire to get the cannon of silencing turned on to oneself is reinforced with the birth of a question. ‘Aik Sawal’ [A Question] reminds us of our eloquent forefathers, who never surrendered to any force of oppression. They offered their lives for truth and their martyrdom became the most powerful voice in support of the oppressed. So, ‘Aik Sawal’ shakes us out of our complacency by boldly questioning the authenticity of metaphorical blood that is silent in times that need speaking:

[Enchained, and compromised by common comforts/ I find myself watching — thinking — / If the blood of these forefathers flows in my veins/ Why doesn’t it cry out?] (Translated by Brenda Walker)

Finally, ‘Elan Nama’ is the proclamation of the reawakening of a young man’s sense of honour, a man who is prepared to offer his life to uphold the truth:

[Now/ The blood of my heroes and martyrs/ Beckons/ So I have brought my head on a platter/ So I have brought my dwelling for devastation/ I may be a helpless coward/ But I belong to that very same tribe] (Translated by Syeda Saiyidain Hameed)

So, this brief review of a few of his poems shows that Iftikhar Arif has recorded silence in stages: from the conception of its necessity all the way to its implementation on the part of the oppressor, and from complete surrender to voiced silence to being ready to speak up even if it costs one’s life. These are the stages through which silence is made productive.

In her ‘spiral of silence’ theory, German political scientist Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann asserts that people tend to become increasingly silent when they believe their views are different from those of the majority. But the theory that emerges from Arif’s poetry shows that creative and critical minds are not bound to any number. Their silence has a lifecycle of its own. Resistant by default, they quickly progress through it and ultimately are ready to speak their hearts and take the blame for it.

The writer is Chair, Department of English at International Islamic University, Islamabad. His most recent publication is his Urdu novel Sasa

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, March 17th, 2019

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.