December 16 passed without much reflection in Pakistan. The date officially marks the dismemberment of Pakistan and independence of Bangladesh, when Dhaka, the capital of East Pakistan, succumbed to attack and fell to the enemy in Pakistani consciousness. The “Fall of Dhaka” does not only denote the traumatic break-up of a country and the tragic loss of its territory, but it also portrays it as part of glorious Muslim past by romanticising its memories.

In Bangladesh, 16 December is celebrated as a public holiday and is officially called Bijoy Dibosh, the Victory Day. In India, the same event is referred to as Vijay Diwas. Bijoy Dibosh or Vijay Diwas both refer to military victory over the enemy. Pakistan commemorates this day by revisiting this episode of its history and digging out the possible reasons for the failures in East Pakistan.

These three modern South Asian states each have martyrs, war memorials and narratives to keep the memories of 1971 alive. The nationalist and militaristic undertones to these narratives have, however, led to the distortion of facts. Such narratives have focused on numbers (of those who died during the war), sexualised violence and they have been used to either humiliate the rival or glorify the bravery of officers and soldiers during and after the war.

Cinematic depictions of the 1971 war have helped the subcontinent to keep the memories of the war alive, albeit through different approaches. Pakistani and Indian movies are mostly about the war machine. For example, Ghazi Shaheed, a 1998 telefilm produced by Pakistan Television, covered the story of the stealthy loss of the Pakistani submarine PNS Ghazi, which sank near Indian waters in December 1971. Ghazi Attack, a 2017 Bollywood production, on the other hand, celebrates the heroics and brilliance of the Indian navy in intercepting and sinking the Ghazi. A short film Mukti produced by Sonyliv in 2017 is described as the story of a war “in which India destroyed half of Pakistan’s navy, a third of its Air Force and a fourth of its army, effectively breaking it to half of its former size and reshaping the global map giving birth to the new nation of Bangladesh.” Border (1997), 16 December (2002), 1971 (2007) are a few more names in this regard.

Why has Pakistani academia largely ignored the events of East Pakistan?

Bangladesh has produced films on 1971 narrating the war through its eyes. These movies, however, are people-centric and focus on the impact of war on people’s lives. The first such film appeared in 1972. Titled Ora Egaro Jon, the film centres around a pro-Bangladeshi freedom fighter. Matir Moyna (2002) Guerrilla (2011) and Amar Bondhu Rashed (2011) are other prominent Bangladeshi productions.

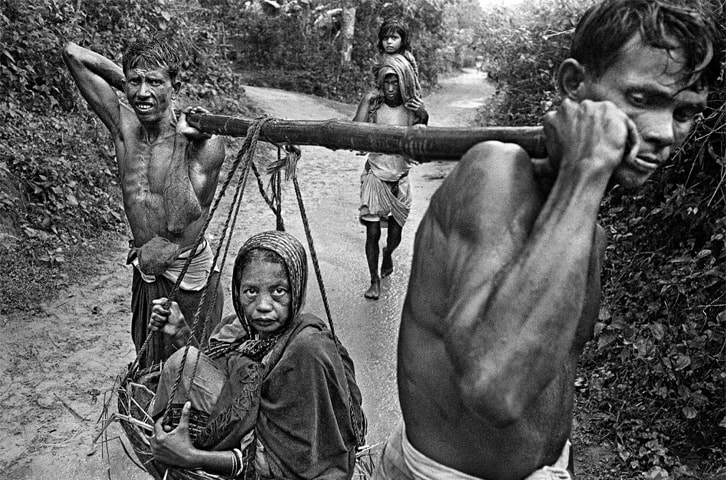

Such narratives present 1971 as a story of one nationalist side or another. They also empty “1971” of human experiences of loss of life, property, homeland and homelessness, of undertaking long journeys to reach the homeland along with the complex violence it inflicted upon the population which experienced the war, not only in East Pakistan but also in West Pakistan . These narratives silence the experiences of POWs and the suffering of their families in their absence and the experiences of Hindu, Muslims and Dalits of Tharparkar where castes and families were affected by “1971”, thousands of miles away from East Pakistan.

On the other hand, in Bangladesh, if someone potrays the war as India’s war (as shown in Mukti), they get labelled as “pro-Pakistani.” Absent here is a comprehensive and objective approach to understanding 1971 as a watershed moment in the history of regional and global politics. What happened in 1971 should not be reduced to the defeat of one country and the victory of another. Neither should it be limited to a clash of interest, and the power games between political elites of the two wings.

Academic material on making sense of East Pakistan and its dismemberment, however, is limited. Traditionally, the trope of “1971” has dominated the academic, autobiographical and artistic discussions of East Pakistan. If the nationalist narratives have silenced the partition of 1947 (Dina Siddiqui, 2013) obfuscating the details of local politics in Bangladesh (former East Pakistan), then Pakistan Studies, too, is no longer interested in investigating East Pakistan. The scholarship on West Bengal, where it attempts to include East Bengal, tends to ignore the policies and politics originating from West Pakistan (Dwaipayan Sen, 2018).

The Pakistani side has kept the discussion on “1971” alive by producing memoirs mostly contributed by ex-officers of Pakistan Army, countering India’s narrative around the conflict. Siddique Salik’s Witness to Surrender (1977) was the first detailed account of the war and life as a POW in India to emerge from Pakistan after the war. Brigadier Sultan Ahmed’s The Stolen Victory (1996) is another important work which provides insights from the battlefield.

The pro-Bangladesh fraction of West Pakistani left has also produced works on East Pakistan. Tariq Ali’s Uprising in Pakistan: How to Bring Down a Dictatorship (2018) is one such title. In recent history, Junaid Ahmed’s Creation of Bangladesh: Myths Exploded (2016) created a brief hubbub in the Bangladeshi parliament. According to a news report, the book was sent to the Bangladesh High Commission in Pakistan and its content denied the numbers of those killed as claimed by Bangladesh. Bangladeshis protested the production of the book and dispatched it to their High Commission in Pakistan. This episode certainly did not help improve any intellectual or academic ties between the two countries.

Among the earlier generation of Pakistani intellectuals and academics who tried to make sense of the breakaway by applying an academic lens was Hasan Zaheer’s The Separation of East Pakistan: The Rise and Realisation of Bengali Nationalism (1994). Two recent academic works, Separatism in East Pakistan: A Study of Failed Leadership (2017) by Rizwanullah Kokab and Secession and Security: Explaining State Strategy against Separatists (2017) by Ahsan I. Butt can also be mentioned here. While Kokab views separatism in East Pakistan as the result of failed political leadership, Butt has one chapter on East Pakistan and approaches the subject from a security studies perspective in his book.

The Bangladeshi intelligentsia has also so far focused on producing memoirs, non-academic, populist and party-centric works building the narrative of the party in the power. This narrative shifts with the shift in regime in Bangladesh. For instance, the two largest political parties of Bangladesh, the Bangladesh Awami League and Bangladesh Nationalist Party, have a serious disagreement over the ownership of the war. So, for example, who led the war in East Pakistan: was it Mujeeb or Zia? And since Islamists cannot claim anything, they question the war altogether. It is the heroic victory that everyone wants to own.

Mustanssir Mamoon and Shariar Kabir are two eminent names in populist, non-academic works on the 1971 war. Widely read writers in Bangladesh, their works have made it harder for new scholars to present their research from different positions. Two names that stand out among the earliest generation of Bangladeshi academics are Rounaq Jahan and G.W. Choudhury. Choudhury contributed The Last Days of United Pakistan (1974) while Jahan’s work Pakistan: Failure in National Integration (1972) looks at the theories of national integration from perspective of a political scientist and tries to explain the dismemberment of East Pakistan.

There are, however, contemporary Bangladeshi academics who are globally positioned and are interested in probing the East Pakistani era deeper. This new scholarship provides cavernous insights into the local and global contexts of the East Pakistani era history. Jute for example, was an important part of early-era Pakistani political discourse on development. Tariq Omar Ali (2018) is the first to offer us an academic account of global trade in jute and the cultural aspects of it at a local level from the nineteenth century to post-Partition Pakistan. Dina Siddiqui’s Left Behind by the Nation: ’Stranded Pakistanis’ in Bangladesh departs from previous studies by making Biharis the subject of her research and, thus, shifts scholarly attention to other groups affected by the war. Layli Uddin’s doctoral dissertation is an important addition in understanding the figure of Maulana Bhashani, a pir and a political leader, and socialist activism in the making and unmaking of East Pakistan.

So far, most of the scholarly work produced on 1971 has been contributed by Indian academics. Yasmin Saikia’s Women, War, and the Making of Bangladesh: Remembering 1971 (2011), Sarmila Bose’s Dead Reckoning: Memories of the 1971 Bangladesh War (2011), Antara Datta’s Refugees and Borders in South Asia: The Great Exodus of 1971 (2012), Sirinath Raghavan’s 1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh (2013) and Nayanika Mookherjee’s The Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public Memories, and the Bangladesh War of 1971 (2015) are all influential works on the subject.

Pakistani academics have, by and large, shown a lack of imagination and, driven by guilt, have decided to pretend that the East Pakistani era is no more relevant to the academic investigation of the region. Pakistani academia needs to revisit the East Pakistani era and rewrite its history instead of avoiding it and fill the gap in knowledge which can only be filled by working in this part of South Asia.

The study of the obfuscated era is relevant to understanding contemporary Pakistan. Without revisiting and rewriting the history of East Pakistani history and politics, one cannot explain contemporary Pakistan to students. Pakistan, in this regard, is still an unexplored field for academics. Much valuable history, oral or otherwise, has remained undocumented. Stories and experiences of people who fled East Pakistan following the war and managed to reach West Pakistan via Nepal or the experiences of Bengalis who were in West Pakistan at the time of dismemberment must be documented. My own doctoral dissertation, for example, explores the 1971 war and experiences of Pakistanis in the Tharparkar region of Sindh province but needs to be complimented by a study from the other side of the border documenting the experiences of Pakistani refugees in India.

There are many other stories which can contribute in making sense of not only 1971 but also of an entire era from various lenses. Not only do we need more academic collaborations in this regard but we also need to open up the official archives on East Pakistan.

The writer is Assistant Professor at Quaid-e-Azam University

Published in Dawn, EOS, March 24th, 2019