LAHORE: Twenty-two-year-old Samreen hugs her baby tightly while sitting on the edge of a hospital bed. Dark circles under her eyes and dark brown patches on both cheeks, she looks sicker than her child who is admitted to the hospital.

Married off at the age of 17, just within a year, Samreen says, her health began to decline after her first baby was born.

“I felt weak and dizzy,” she says, adding that she often feels the same even now after two children. Despite this she is expected to do the household chores – washing, cleaning, cooking -- as well as care for the children.

“Everybody in the family knows about my health, but there’s not much that can be done about it,” she says. “I also must not pressurise the family about it.”

Meanwhile, 32-year-old Maryam is also in a state hospital’s paediatric ward with her second child, who is quite underweight. Her first baby was born with a lot of difficulty after 10 years, but the second one was malnourished and keeps falling sick.

“I had (gestational) diabetes and high blood pressure in my last trimester, and was told this may have been the reason for the child’s stunting,” she says. Maryam says she is often depressed and stressed out because her husband is a heroin addict and does not work. Instead, she works as a ‘nursemaid’ in a nearby school.

The last National Nutrition Survey (2011) says that there is approximately 46 per cent Vitamin A deficiency in mothers, while in children it is 54pc; anaemia deficiency is 54pc in mothers and 62pc in children, and Vitamin D deficiency is 67pc in mothers and 40pc in children. The survey also noted that the indicators of mother and child nutrition had not improved in the past decade.

Breast feeding – to combat multiple diseases in infants – is recommended, but largely mothers in Punjab do not breast-feed or discontinue before a child is six months old. The most common factor behind malnutrition is nutrient deficiency.

Dr Yasir Bajwa, a paediatric expert, says that around 60 to 70pc of mothers who come in with their children are themselves malnourished. “Most frequently, we find that they are low on iron and folic acid, while Vitamin D3 and Calcium are deficient across the population anyway,” he adds.

Effects of malnutrition in mothers translate into lethargy and weakness, lowered productivity, compromised immune function, increased risk of infections, frequent pre-natal complications, and increased risk of death. The mother’s health directly affects the child’s, hence malnutrition among children is also quite high.

With children, the effects are intra-uterine growth retardation, compromised immune functions, birth defects, cretinism, reduced IQ, and foetal and neonatal deaths.

According to the Punjab Bureau of Statistics Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019, one in every five children in Punjab is underweight for his/her age and this is most common among infants less than six months old. The effects of nutritional deprivation as measured by stunting can be life-long and may include impaired mental development, poor school performance, and for girls difficulty in giving birth and also a higher likelihood of having a low birth weight baby.

In 2013, the government launched a ‘Scaling up Nutrition Programme’ to overcome malnutrition in mothers and children. The programme aimed at identifying reasons for lack of access to food.

Salma, a resident of Lahore, was married at 16 years of age and gave birth to her first child within a year. Today, she has five children, but her fifth child was born with a startlingly low birth weight. The three-month-old baby girl, with wrinkled skin and stick thin arms and legs, weighs only 1.5kg. For Salma, it is because of someone’s “evil eye” as all her other children were born normal. Meanwhile, her own health is grim too with liver problems and overall nutritional deficiency. Her skin is patchy and yellow.

“I have a blood problem,” she says -- not entirely clear on what the cause of her illness is. “I feel dizzy and weak all the time.”

There are several reasons why mothers end up in this state. Malnutrition could be prevented in many cases, but only worsens because of what doctors say are “psyco-social” or family pressures among other issues.

“Early marriages, lack of education and awareness, large families, poverty, less food – all these are factors leading to problems of malnutrition among women, which in turn cause malnutrition among babies,” says Dr Ali Khwaja. “There are also hygiene issues, as most families in rural areas do not even have a toilet, while in other places it is shared and unhygienic.”

He says the biggest problem is that much like depression malnutrition is not regarded as a disease. Some babies are so small and weak it is impossible for them to even feed on breast milk. At the same time undernourished mothers cannot produce breast milk. To make matters worse, some elders impose decisions and quite often a small child is seen being given cow milk, which can be very bad for the digestive system. Meanwhile, mothers bear the brunt of food insecurity in the house and consume the least food, or an imbalanced diet.

There are cultural barriers too. “We have seen very few women being supported by their in-laws or husbands in being admitted to hospital for treatment,” Dr Khwaja says. “In most cases, they are discouraged and their disease or illness is waived aside as easily treatable at home.”

Poverty plays a huge role in food insecurity, while lack of birth spacing leads to serious deficiencies and weakness for the mother.

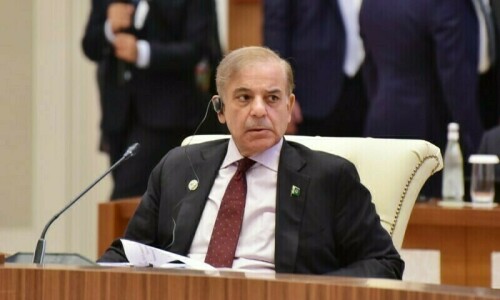

The recent announcement by Prime Minister Imran Khan about the first “multi-sectoral nutrition coordination body” to be constituted at the Prime Minister’s Office has given some hope for those fighting against this disease.

However, specialists, who see cases of malnutrition every day, say that there is a long way to go.

Published in Dawn, April 13th, 2019

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.