Is the PTI budget sustainable for an economy like Pakistan's?

The Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) government presented its first full-year budget for the 2019-2020 fiscal year on Tuesday, with a heavy emphasis on increasing revenue through taxes in line with the latest agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Prism spoke to experts to make sense of the budget's implications for taxpayers, trade deficits, growth and the government itself.

"Erosion of purchasing power"

—Maha Rehman, Center for Economic Research Pakistan

Following the IMF bailout and given our historical budgeting and policy design patterns, a budget of the nature presented was more or less expected.

Taxes on commodities of everyday use have been increased, exemptions on the import of LNG have been removed, tax exemptions on the current exporting industries have been done away with and tax exemptions for the salaried class have been reversed.

The most immediate and visible consequence of this package is the erosion of the purchasing power of the common man. On a more macro level, with the removal of exemptions for LNG and given our current exporting industries, the cost of production will increase, making our goods less competitive in the global market.

What you need to know: Indirect taxes in Budget 19-20

Contracting demand and dampened exports are likely to lull us back in the negative feedback loop that follows every major IMF bailout. And this is what Pakistan’s economy needs to structurally avoid if we are to disentangle it from international dependencies.

To meet our revenue targets, we not only need to restructure the tax regime, but couple this with structural reforms that provide the right incentives for higher tax collection by increasing operational capacity.

Additionally, the long-term macro goals demand that structural changes boost export capacity and encourage investment in new export industries. It is the macro, long-term perspective that needs to be kept front and centre.

"A very ambitious revenue goal"

—Shahrukh Wani, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

The government wants to try every possible trick in its book to raise more revenue. This is what this budget is about.

There is no way around this; the government needs to raise more taxes as part of its agreement with the IMF, and the proposed budget proposes to do precisely that.

The budget rests on a very high revenue goal when economic growth has slowed down dramatically. At the risk of speculation, this might become even worse: if the government is unable to achieve this revenue, it might, I fear, review spending plans and cut down development spending — reducing growth further.

The coming year is not going to be easy, not only for the government to achieve these targets (for example, the surplus they expect provinces to achieve), but also for the people, who will have to make do with a slowing economy, more taxes (a bulk of which are going to be used to pay off debt) and rising inflation.

Tax amnesty: Is PTI packaging gimmicks as economic reforms?

There are three adverse consequences of this budget which we need to look at over the coming year:

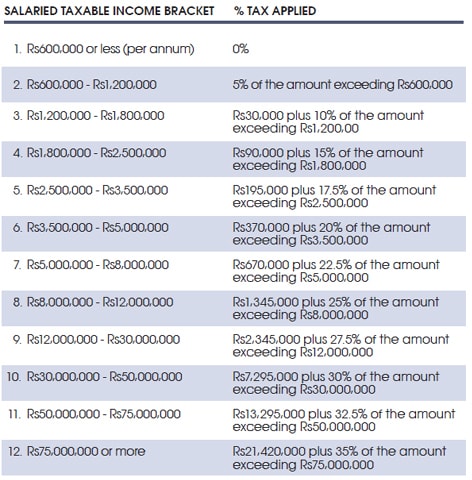

The impact of increased taxation on people's spending capacity — for example, a person making Rs50,000 a month will have to pay income tax, along with exposure to the broader impact of inflation due to the devaluation of the rupee and increase in sales taxes.

The dramatic decrease in higher education spending (via the PSDP) is going to have a significant impact on the quality of universities and research. This might be the single worst choice made by the government in this budget.

The budget is also going to allow non-tax filers to purchase property worth Rs5 million or more. This is going to push people to move capital towards the non-tradable sector — an incredibly bad incentive for people to move capital away from productive sectors.

Beyond the budget and stabilisation measures it tries to bring with it, what is more important is that the government is willing to bring in structural reforms targeted at increasing economic growth and exports.

We missed all economic targets (except one) last year; that reflects something deeper at fault in our economy. Changing that requires thinking about how to improve the performance of the government, incentivising firms to grow and giving the people skills; the government needs a broader framework to do this.

That is going to be the real test of the government, and if they ignore these structural reforms, we will need one of these 'tough' budgets again soon.

"IMF will hold the government’s feet to the fire"

—Uzair Younus, South Asia Practice at the Albright Stonebridge Group

The Achilles' heel of this budget is the revenue target, which is set at Rs5,555 billion. I do not see a plausible way where the government meets this goal. This means that the IMF will push the government to unveil additional tax measures through mini-budgets.

Missing revenue targets will also mean increased reliance on borrowing to meet fiscal gaps, leading to increased inflationary and interest rate pressures on the economy.

The first quarter of the new fiscal year will set the tone. If the government is unable to meet its own revenue targets, then we can expect some tough conversations between the PTI and the IMF.

Budget 2019-20: IMF hand clearly visible in budget proposals

The next 12-24 months are not about reviving economic growth. They are going to be focused on stabilising the economy and getting the fiscal and current account deficits under control, while shoring up reserves.

Expanding the tax base will be the real test of the PTI government. They’ve set an ambitious target for themselves and appointed a private sector tax expert to achieve these goals.

In the short term, the only way to raise revenues is to squeeze the existing tax base. In the medium term, the Federal Board of Revenue chairman Shabbar Zaidi’s tax reforms may bear fruit and the economic prospects of this government will depend on his success or failure.

The latest budget is guided by the agreement made with the IMF, and the IMF will hold the government’s feet to the fire the moment agreed-upon targets are missed. Every review cycle will create pressure on the government to hold its end of the bargain.

"Expect higher inflation and a tighter job market"

—Hina Shaikh, International Growth Center

Pakistan’s economy can only be fixed if we address its most fundamental structural flaws. This requires an understanding of what ails the economy — a disparity between public sector spending and income, and an underdeveloped export base.

On one end, we need sustainable and reliable flow of income — hence an increase in revenue generation. We need tax reforms to focus on progressive taxation and reduce reliance on indirect taxation and thus protect the interests of the low-income strata.

On the other, we need to rationalise expenditures, reduce losses of state-owned enterprises and streamline government machinery. We need a strong export base and a strengthened business environment with a strong private sector engagement.

The budget focuses on some aspects of the critical interventions needed to boost the economy, but there are glaring contradictions as well.

Attending to IMF conditions, a one-time sacrifice of the defence budget’s increment, more income tax slabs and higher sales taxes are temporary measures to provide breathing space to help avert a current fiscal crisis.

The government is still committing to a high fiscal deficit at 7.1 per cent compared to 7.2pc of GDP in the last year, owing primarily due to the large size of the debt repayments. In addition, the government has announced highly challenging revenue targets in a low-growth period, relying mostly on taxes to be collected from the masses.

This is despite a recent World Bank report confirming that Pakistan is capturing only half of its revenue potential and needs to raise revenues by enhancing tax compliance — not levying new taxes or increasing rates.

In the short run, these budget commitments may become unsustainable, necessitating interim finance bills to provide quick fixes.

Also read: How can we protect contract and informal workers in Pakistan?

Any successful IMF programme requires government commitment to policies (some painful) that are outlined in the programme.

Associated with a new loan will be extensive pressure to reduce aggregate demand of which the largest burden will be on the fiscal side. A limited fiscal space can hamper Prime Minister Imran Khan’s efforts to substantially enhance public spending and also hit economic growth.

What we can expect before the next budget, in the face of an economic slowdown, is higher inflation and a tighter job market as economic activity takes a hit.

Some of this inflation could be offset if income taxes were lowered, but that is not the case as Pakistan sets its sights to grow tax revenues at the fastest pace in recent years. With less than 1pc of 208 million people filing returns, it may be difficult to meet the ambitious revenue targets.

While a slow-down in the demand for imports will help to prevent the dollar drain and reduce the trade gap, and higher taxes along with spending cuts can help reduce the budget deficit, the government may save enough to spend on development projects.

But this process will take time. It may take two years before economic growth can bounce back and the government is able to fix the larger macroeconomic problems. If not, then we could be looking at another bailout.

Illustration by Rajaa Moini