Journey to Kangchenjunga, Nepal’s hidden jewel — Part I

Read Part II of this travelogue here.

After my last trip to Gondogoro La, a friend asked me where I was headed to next.

“Mount Kangchenjunga”, I replied. “Mount Kangchen- what?” she asked.

I was not surprised — not many people know about or even heard of Kangchenjunga. This despite the fact that at 8,586 metres, it is the third highest mountain in the world, after Mount Everest (8,848m) and just 25m shy of the second highest K2 (8,611m).

Kangchenjunga was once assumed to be the highest mountain, a status it lost in 1852 after The Great Trigonometrical Survey in India established Everest as the highest mountain. K2 was measured second highest and Kangchenjunga third.

About Kangchenjunga

Lying on the border between Nepal’s yet-to-be-named Province No. 1 and the Indian state of Sikkim, Kangchenjunga is the eastern-most of the fourteen 8,000-metre peaks and the only one in India.

The word Kangchenjunga is Tibetan and means 'the five treasures of high snow', treasures referring to the five peaks of this massive mountain. Four of these cross the 8,000m mark (Kangchenjunga Main 8,586m, Kangchenjunga West 8,505m, Kangchenjunga Central 8,482m, Kangchenjunga South 8,494m and Kangbachen 7,903m).

These peaks do not classify as individual mountains by themselves due to their lack of prominence.

Also read: How my love for the mountains took me from Hyderabad all the way to Everest Base Camp

The first successful ascent of Kangchenjunga was in 1955 by British mountaineers Joe Brown and George Band.

Locals in the area believed that spirits or mountain gods live on the mountain summit that must remain undisturbed. In respect, both Brown and Band intentionally stopped short of the summit, a tradition that every climber has followed since then.

The mountain has three faces: North and South in Nepal, and East in Sikkim. In both Nepal and India, the area is protected by wildlife conservation. It is home to the blue sheep, red panda and snow leopard, among others.

Why Kangchenjunga?

What really caught my interest in Kangchenjunga was the lack of information available on this mountain and area.

In the last few years, both Everest Base Camp/Kala Patthar and K2 Base Camp/Gondogoro La have soared in popularity, but Kangchenjunga still remains hidden from the eyes of outdoor enthusiasts.

It does not have the highest mountain tag of Everest nor the legendary status of K2. The area was also affected by the Maoist insurgency in Nepal from late 1996 to 2006 and although now it has subsided, the interest never returned to Kangchenjunga.

However, the lack of visitors has really preserved Kangchenjunga in a pristine state. At the Everest Base Camp there are queues at key viewing points and yak waste is all over the trek, just like mule waste is on the K2 base camp trek.

You will not run into that on Kangchenjunga.

For me, it was a personal goal as well. I had already explored base camps of the two highest mountains in the world: Mount Everest in 2017 and K2 in 2016. By completing a trek to Kangchenjunga, I would have completed the triple crown of base camps.

How to get there

India was out of reach, so I never really explored the option. It is known that on a clear day, the Kangchenjunga range is visible in Sikkim as far as Darjeeling.

In Nepal, you can trek to the North Base Camp (Pang Pema), South Base Camp (Yalung or Oktang) or complete a full circuit that combines both camps but requires crossing a series of non-technical high passes (Sele La and Mirgin La).

I called my Nepal advisor in Kathmandu, Anil Bhattarai, to discuss the possibility. Anil had previously arranged the logistics for my Everest base camp expedition.

He was very excited about my interest in Kangchenjunga since he hailed from the same area. He advised me to go for it instead of other, relatively more commercial treks.

Arrival in Kathmandu and journey to Taplejung

With all formalities sorted, I landed in Kathmandu in early March, where I stayed for a full day to get my trekking permit for Kangchenjunga.

Since Kangchenjunga lies in a wildlife conservation area and due to its close proximity to the Indian and Chinese borders, a special permit is needed from Nepal's Department of Immigration, unlike for other trekking areas.

The next morning, a 40-minute flight took me to Bhadrapur in eastern Nepal, one of the lowest lying areas of Nepal at 175m.

Here at the airport, I was received by mountain guide Dilli Bhattarai and our porter Neema Sherpa. Both were from Taplejung and made their living through tourism.

From Bhadrapur we took an uncomfortable eight-hour drive to Taplejung through switchbacks, where the car speed hit 50 kilometres per hour just four or five times.

We stayed overnight in Taplejung and then drove another six hours the next day to Tapethok.

Tapethok is the end of the road and beyond this, one has to walk into the Kangchenjunga area for the North trek (the South trek starts in Mamangkhe).

Walking into Kangchenjunga

On the trail, we walked around 7.5km in three hours to reach the small settlement of Sekathum, where we stayed at a local lodge run by a Sherpa couple. We affectionately called them Dai and Didi (brother and sister in Nepali).

It is here that I got my first taste of daal bhaat, a Nepali dish of lentils, rice and vegetables (mostly saag and potatoes). This would be our dinner for the next many days on the trek.

Walking through farms and tea gardens

The next morning we were on the trail early, following the Ghunsa River (Ghunsa Khola in Nepali), melt from the Kangchenjunga Glacier. We would be following this river for the next four days to Lhonak, where the glacier begins.

We passed through cardamom, potato and corn fields near Sekathum. Somewhere in the middle, we stopped for tea at a small shop on the trail.

A few minutes later, we were back on the trail. Standard treks rest overnight in Amjilosa, but we pushed to reach Thangyam, where there was just one house. A young Sherpa couple, with a newborn, were running a very basic lodging facility.

We had trekked 16km and climbed up to 2,375m in 6.5 hours.

From Thangyam, it took us 14km in 7.5 hours to reach Ghunsa at 3,400m. We passed through dense rhododendron and larch forests, with views opening up occasionally but mostly blocked by the trees.

We had two stops this day, first in Gyabla where we had tea at a home shop run by a Sherpa lady. Our second stop was at Phale, but Ghunsa was waiting.

Ghunsa is the main town in the North Kangchenjunga area with approximately 35 houses, all belonging to the Sherpa community.

It is to Kangchenjunga what Namche Bazar is to Everest, except there is no bazaar, wifi or phone signal in Ghunsa. The village does have electricity, telephone lines and a primary school though.

All campsites on the North Kangchenjunga trek are run by people from Ghunsa. Here we had to check in with Security and Wildlife Conservation personnel. We stayed at Peaceful Guest House, another Sherpa family-run business.

Spotting the yeti footprint

In my opinion, it is after Ghunsa that the spectacular views of the Kangchenjunga area begin to appear. I prefer trekking in the open where I can view the mountains and valleys, not through forests where the views are blocked by trees.

There was still snow and ice on the trail north of Ghunsa, so we had to be careful now, avoiding slips and injuries. We left around 8am in the morning and shortly after, noticed humongous footprints on the icy trail.

Dilli, my energetic mountain guide, really tried to convince me that it was the footprint of a yeti.

A yeti is an ape-like creature thought to exist in the Himalayas. Sightings have been reported by locals, guides, mountaineers for decades, but the scientific community still denies existence and treats it as a variety of bear in all likelihood.

While locals in Tibet, Bhutan and Nepal still believe the monster exists, for the outside world, the yeti remains a legend from folklore.

Dramatic night at Khambachen

Back on the trail, the weather got a little gloomy as the day progressed. We made our way through the snowy trail, passing through some bridges to reach Khambachen before 1pm.

It took us four hours and 30 minutes to complete the 11km trek and climb from 3,400m to 4,100m. We had plenty of time to rest for the next day but later, after darkness fell, the dramatic sky could not let me sleep.

There were mountains, glaciers, clouds and stars all around. How could I sleep with all of that? How could anyone sleep?

I stayed out late that night taking pictures in subzero temperatures, only retiring back into my sleeping bag when my fingers and toes couldn’t bear the cold anymore.

It was here at Khambachen where we met for the first time on this trip a team other than ours, a duo of European climbers also headed to the North Base Camp.

It was their rest day in Khambachen and they were planning to trek to Lhonak the next day, same as we were.

I must admit, I was getting spoilt having the entire trek and camps to myself.

Breakfast with Kumbakharna, Ravana’s younger brother

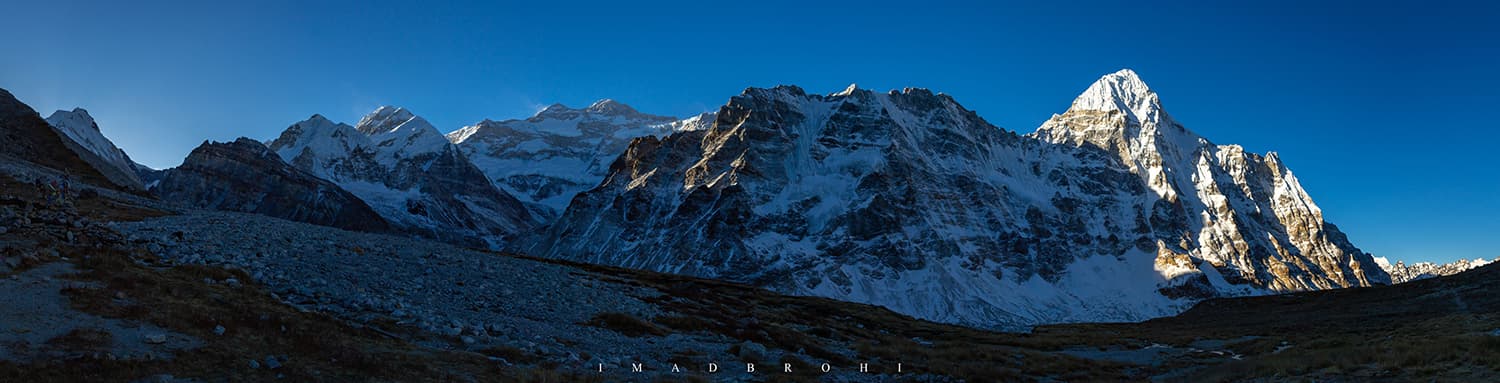

The morning at Khambachen was magical. While the mountains were glowing in sunlight, the valley still remained dark and the sky was a shade of dark blue which we never see in cities.

Here we got our first and what would be the only views of Kumbakharna (also called Jannu Peak). Named after the younger brother of Ravana in Hindu mythology, Kumbakharna is the 32nd highest mountain in the world at 7,710m and one of the toughest to climb.

Two fried eggs with pancakes and black coffee and we were on our feet again to march to Lhonak, the last site before the North Base Camp (Pang Pema).

I must admit, it was the most fascinating day of the trip so far. The Himalayas north of Kangchenjunga appeared in all their glory under the spotless sky.

Looking for the snow leopard

It was here on our way to Lhonak where we spotted some blue sheep, grazing on the greens of a mountain slope.

I was told that we were in snow leopard territory. Makes sense for the predator to live where there is hunt available. I was really hoping to catch a glimpse of one and got my extended zoom lens ready, but all I could shoot was the blue sheep.

The probability of me spotting a snow leopard was as high as that of spotting a yeti. Wildlife conservation officers who have spent decades here have rarely seen the elusive beast.

Confluence of Lhonak and Kangchenjunga Glaciers

Lhonak is where the Kangchenjunga and Lhonak glaciers meet, though both may have receded back now due to climate change.

The glacial melt from the two forms a pond or small lake just before Lhonak, which was frozen in March.

We walked carefully on the ice sheet, bypassing any cracks to avoid falling into the water underneath and reached Lhonak at 12pm exactly.

It took us four hours to complete 11km and climb up to 4,800m approximately, which was very fast and none of us were feeling tired either.

Kangchenjunga North Base Camp (Pang Pema)

Ten minutes later, while sipping hot tea under the clear sky at Lhonak, we decided to push for the North Base Camp the same day.

It was certainly doable, except we weren’t sure if we’d be able to return in time.

So, our strong porter Neema agreed to carry the sleeping bags while Dilli and I shared the load of the food items. At roughly 12:40pm, the three of us were on our feet again, heading for the base camp.

Severe landslides had eroded the trail that was used in the past season, extending our efforts to reach Pang Pema (a term used to refer to the North Base Camp of Kangchenjunga).

Slowly, the peaks of the Kanchenjunga massif appeared — but the problem was that we were now racing with the storm to reach the base camp.

Severe winds from the south were blowing clouds towards the base camp and I was barely able to take one shot of the main peak before everything was covered in fog.

Spending the night in starlight at Kangchenjunga

Here we decided to pitch tent and spend the night at the base camp. There was no one there except us, and I was excited that once this fog cleared up, I would have the third highest mountain in the world all to myself.

We had tea and snacked on two-minute noodles cooked melted snow before it became so cold that all three of us were in our sleeping bags around sunset.

By then it had started to snow as well, just a few flakes. However, around midnight the clouds were all gone and there was just the mountains under starlight.

So many stars covered the entire sky that it became difficult to spot the easiest of stars and constellations. I shot hundreds of pictures, once again in below-freezing temperatures and finally retired to the cosiness of my sleeping bag. I still regret not staying awake the whole night.

Magical morning at Kangchenjunga

Waking up the next morning, there was magic at sunrise once again. As the sun rose, casting light on darkness, the sky remained unsure, half lit, half dark.

The mountain peaks were shining from the first rays of the sun but the valley was still dark. We munched on our last few remaining biscuits and I took our last photos of the mountains here at Pang Pema.

As the day got brighter we also noticed how overwhelming the Kangchenjunga glacier was once it started to glow in sunlight. Soon we were heading back to Lhonak and I wondered, why so early?

We left the camp at 8am to arrive in Lhonak around noon, completing the 8km trek in four hours. At Lhonak, a lone Sherpa was waiting for us. He had ascended up from Thangyam in hopes of working for us.

He rented a room and cooked meals for us while we were there. Except us, there was no other team at Lhonak. The Europeans we had met in Khambachen had trouble with altitude sickness and decided to descend earlier.

We too spent a night in Lhonak before descending to Ghunsa. Our first leg of the circuit, North Kangchenjunga, was over and it was time to head for the South.

Return to Lhonak and Ghunsa

It took us two days from Kangchenjunga North Base Camp to return to Lhonak and then Ghunsa. On our way to Ghunsa we stopped over at Khambachen to have lunch.

Crossing from North to South Kangchenjunga

The transfer from North Kangchenjunga to South Kangchenjunga (or vice versa) is possible via non-technical passes Sele La/Mirgin La that connect Ghunsa in the North to Tseram in the South.

During a regular season, crossing the path is simple. Trekkers and climbers from Ghunsa ascend to Sele La, where they spend a night at a lodge before crossing Mirgin La and descending to Tseram, which is two camps away from South base camp.

But as luck would have it (or the lack of it), the past winter saw record snowfall in the area. Taplejung, which had not had any snowfall in half a decade had received snowfall as many as six times.

Thanks to the heavy snowfall, we were told by the Sherpas at Ghunsa that the lodge at Sele La was still closed and parts of Mirgin La had snow up to waist-height.

Even the tough Sherpas were avoiding the Sele La for now and when Sherpas avoid a route in the mountains, we don’t challenge that.

Dilli, Neema and I stayed the whole evening in Ghunsa, going over a map of Kangchenjunga that I bought in Kathmandu and pondering possible alternate routes to cross to the South.

It was a special evening though. The family that ran the lodge had invited local villagers. They sang local folksongs of while we all sipped home-made Himalayan salt tea, made with salt and yak butter.

Are you out exploring remote regions? Share your experience with us at prism@dawn.com