I was eight years old then but I vividly remember the bright day of July 16, 1961, when we took a public bus to go to my grandparent’s house in another part of Baghdad. My parents were unusually quiet throughout the journey and when we reached there, things did not seem normal.

It was the day that we found out about Uncle Ijaz’s accident that had happened a week earlier near Konya, Turkey. He and his three friends — including an Iraqi, an American and another Pakistani — had all died. He was only 25. This was the first time that I saw my grandfather crying.

Because of his cheerful and generous nature, Uncle Ijaz was everyone’s favourite, especially the children, in my grandparent’s large household. He was considered the best-looking among my five uncles and had a wardrobe full of elegant and expensive clothes. He had many interests including reading and listening to music. One of his interests was making pen pals. I guess one could call it a primitive form of chatting on the internet.

A nephew traces his uncle’s lost love in Turkey, some 40 years after his uncle’s death

After learning about the accident, my grandfather travelled to Turkey to take care of the formalities, arrange a proper burial and collect my uncle’s belongings. A year or so later, I accompanied my parents to Turkey to visit his grave.

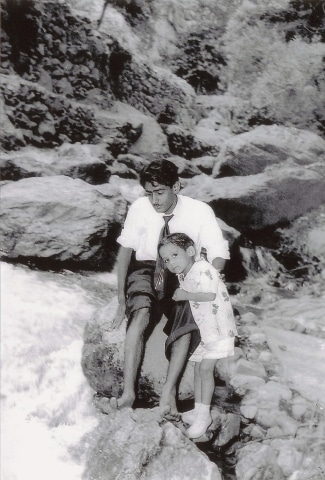

One of the things that my grandfather had brought back was a medium-sized envelope containing a bunch of letters in English, which I couldn’t read then, and black-and-white photographs of Uncle Ijaz and a young woman, taken in and around Istanbul. My father tucked away the envelope with his papers and files.

Several years after we had returned to Pakistan and I was in high school in Karachi, I came across the brown envelope. By then I could read English reasonably well and was also able to make more sense of the photographs. The letters were written by Uncle Ijaz to a young woman living in Istanbul. Apparently, when my grandfather went to Turkey, he met this young lady and she had returned those letters to him. The letters unfolded a relationship initiated as pen pals but one that turned into something more serious over a span of three years, until just before the unfortunate accident. Most of the elders of my family knew about it and some of them had even met the Turkish girl and her family during my uncle’s life.

The letters read almost like a movie script: the introduction, beginning of a friendship and then its blooming into passionate love, before finally ending in heartbreak — very romantic, very real. The first letter he wrote is dated June 8, 1958:

Ijaz Ahmed Piracha, PO Box No. 263, Baghdad, Iraq June 8, 1958 Dear Miss Semsa, A Pakistani friend of mine Mr Ismail, who previously had visited Istanbul and became a friend of yours, on my request, gave me your address. Being myself very much interested in making pen pals everywhere, I wish to make friendship with you, that is, of course, if you are ready for it.

I am 22 years old, completed my high school last year from the Punjab University (Pakistan). In Baghdad, I help my father in his business whenever possible, otherwise I spend most of my time writing letters to my pen pals or reading some detective novels. I like Western music, and I have a very good collection of musical records of English, French, Indian and Arabic songs. I also like travelling and every year I travel to some foreign country. This year I am coming to Turkey and I hope to arrive in Istanbul on August 5, 1958 for about two weeks’ stay, I have already booked a Single Room in Hilton Hotel Istanbul from August 5 to August 20, 1958. As a matter of fact, I have heard a great deal about Istanbul and so I made up my mind to spend this summer there. To be very honest, my very important reason of making friendship with you is to know more about Istanbul and other cities in Turkey…

Thus began a correspondence which turned into friendship and eventuially led to their engagement. Both the families were informed, although it was not a ‘done’ thing in those days; marriages were arranged by parents, especially in our family. To marry outside one’s tribe, not to mention a different nationality, was taboo. No one apparently objected except my grandmother who had her own ideas and, to put it mildly, she had a say in the family. She undertook a 10-day sea voyage from Basra to Karachi to find a suitable girl for my uncle and when she did, she telegraphed her decision to the rest of the family in Baghdad.

In one of his later letters my uncle wrote:

Baghdad 25.9.1960 Dearest Semsa, The last 10 days have been so painful that sometimes I think I’ll go mad. I have been crying whenever I was alone and I have been having lots of troubles in my office because I couldn’t do my work properly. There is no one in Baghdad to whom I could talk or tell my troubles …

… it was all decided by God that we meet, we fall in love, plan to get married and then I get engaged to this girl (believe me, I don’t even know her name!) and we separate, separate because that is how it was decided. I know it is cruel, it is unfair and dreadful but can we change it? Can we do anything about it?

It does not help to say that I am sorry although I am hopelessly and bitterly sorry.

PLEASE FORGIVE ME.

Ijaz

For my impressionable mind this whole fascinating real life affair, complete with pictures, letters, gossip and a tragic ending, was etched in my psyche. I seemed to have begun a renewed relationship and a close connection with an uncle I had lost in childhood. I no more saw him as a child looks at an adult. It was like one young adult idealising an older, more experienced adult. On and off, I would take out the pictures and letters and fantasise being like him and visiting all those places he had been to. I wished that my uncle had lived longer so that I could have known him and his life better and Turkey in particular. I wished I could meet his fiancée, talk to her about him and their aborted love affair. The fascination continued to grow in a nostalgic way, though deep down I knew that it was a past, dead and buried forever.

The subsequent four decades took me to dozens of countries, but never to Turkey, until my incurable urge to discover new places took me there in 2005. By then, the joys, miseries, frustrations and successes of work, family and the world around me had faded Uncle Ijaz’s memory and my fascination with him, but not completely. Before my departure, I dug up the letters and tossed them in my briefcase. On one of these discoloured, wrinkled old letters, the young lady’s address was scribbled.

Istanbul was bright, cheerful and cold in the early morning of February 2005, when I came out of the airport building. It is one of the most beautiful cities in the world, bridging Asia and Europe; with such a rich heritage that few other cities can match. Just Istanbul, a city of over 10 million, has so much to see and experience that one needs weeks to savour it.

During a visit to Princess Island by ferry and over a delicious seafood lunch with Chris, who is Greek, and his British wife Beverley, the fellow tourist couple asked me, “Have you been to Turkey before?” That took me to the trip I made in my childhood, and to the subject of my uncle and his fiancée.

“If I were you, I would just take a taxi and go to that old address you have and try to trace her,” said Chris excitedly. “I can go with you if you want.” He could speak Turkish, I couldn’t.

The next day I did exactly that. Took a taxi and went to that address (but without Chris!). It was in the suburbs and we had to drive in several streets looking for a house which, for all I know, may or may not still be there after 40 years. Fortunately, I met an old tailor who knew the family I was looking for and said they had gone away a long time ago, probably to Germany. I asked him if he knew any friends or relatives who might be able to help get in touch with them. He said he would find out whatever he could, and that I should get in touch with him in a week or so.

I headed to my other destination. There were two reasons for my visit to Konya. To see the whirling dervishes at the tomb of the 13th century mystic poet Jalaluddin Rumi, and perhaps to get better acquainted with Sufism and its history. The second was that Uncle Ijaz is buried in Eregli, a small town near Konya. For the past several decades, no one from our family had visited his grave. I thought perhaps I would be able to locate it and pay my respects.

On a bright, cold and windy day I got down from the minibus in the centre of the Eregli. I knew no one and had no address or location of the grave or even the graveyard. I looked around and asked myself what the hell I was doing there.

Failing to find anyone who could speak English, Arabic or Urdu, I looked for a police station, thinking there may be someone I could communicate with and ask where the graveyard was and that if there would be a possibility of finding a record of that fateful traffic accident in which four foreigners had perished. Though I found a police station, there was no one there who could speak to me in any language except Turkish. I tried a hotel receptionist for translation but had no luck.

Then I saw two important-looking gentlemen in overcoats come out of a building which looked like a government office. One of them could speak Arabic. After instructing someone to help me out, he left. The young fellow, who they thought could speak English, actually couldn’t. So I asked if we could contact the boy’s English teacher and the idea worked.

Sahin Ercan turned out to be a kind person who spoke English well. He took me around in his car to the police headquarters and municipality offices for checking records, which turned out to be too old to be found in such a limited time. Then, accompanied with an old gentleman who could speak Urdu, we went to two of the three graveyards. It was getting dark and we were frantically looking at each gravestone for something familiar. But no such luck. However, within four hours I was transformed from a lost stranger to someone surrounded by friends who insisted that I have dinner with them and spend the night as their guest. I had to (literally) beg their leave and returned to my hotel in Konya by 11 pm, unsuccessful in my mission to locate uncle Ijaz’s grave.

Upon my return to Istanbul after 10 days, I contacted the old tailor who had promised to find out about Semsa’s family. Unfortunately, he still had no news, and asked me to give him a few more days. I was losing hope of finding her and, in any case, in two days’ time, I had to return home to Pakistan. I guess I waited too long to make this journey. It was a disappointment, even though I had a wonderful time in Turkey.

A few days later, as I arrived in my office in Karachi, I saw a fax on my desk. It read:

Dear Mr Piracha, I understand you have been looking for me. I wrote you an email and tried to call on the phone this morning. Please send me an email first, at … I hope to hear from you. Semsa

Unbelievable! I read it again.

A short while later, my phone rang, I picked up the receiver and a female voice, with a foreign accent, on the other end said in English;

“Can I speak to Mr Imtiaz Piracha?”

“This is Imtiaz. May I know who is calling?”

“This is Semsa from Istanbul. Which Piracha are you?” asked a high-pitched, strong female voice.

“I am Ijaz Piracha’s nephew, his elder brother’s son.”

“O my God! My faith in God is going to be restored! I just got the message that you were looking for me. What a pity we couldn’t meet.”

“I am completely surprised too. I don’t know what to say!”

It was the weirdest and most incredible phone call I have ever received! We exchanged emails and continued catching up about a past when telex and fax machines were yet to be invented and the old-fashioned paper and pen were the main tools of communication, when it took days, if not weeks, to receive a reply while the photographs were all in black and white!

Semsa works in publishing and has translated 27 American and English books into Turkish, I found out. We soon realised that there was such a huge gap of time and space between us yet so many common interests that we would simply have to meet in the near future. Although we had never met nor spoken to each other previously, yet there seemed to be a strong connection between us.

In her recent email she wrote to me:

I have always been very active, humorous, and hard working ... We shall see how long it will last.

I am happy to have found you, because for some reason I feel your family wanted Ijaz to marry me more than he himself did probably. (So I feel part of the family maybe?) Ijaz’s brother came to Istanbul and brought me a cardigan saying that his mother sent it ... How badly I wanted to see Ijaz’s mother, Razia, and the rest of the household. I had felt at the time that if jaz were more clear about marrying me, things could have been different and I even went as far as to think that he would not have died if he wrote to me that he was coming to Turkey to see me. He had come out of [the] blue, could not find me and — crash! That was a pity ...

The following February, Semsa arrived in Karachi and stayed with us for 10 emotionally charged days. Just before her return, while we were driving one day, she said, “I have been looking, but have not seen a single man as handsome and attractive as your uncle was.”

Note: Semsa Yegin died in December 2015. Before her death she published her autobiography in Turkish (Hayal Molalari) in which she devoted a whole chapter to this event.

The writer is a freelance journalist and translator

Published in Dawn, EOS, September 1st, 2019