As is well known, in 1947-48, thousands of Hindus and Sikhs migrated from Sindh to parts of newly demarcated India. Across the border, they were successful in “transplanting” several of their institutions from Sindh: schools, colleges, nari shalas [homes for destitute women], panchayats and more. One such institution was the Khudabadi Amil Panchayat, which was relocated to Bombay [Mumbai] where it continues to operate till today.

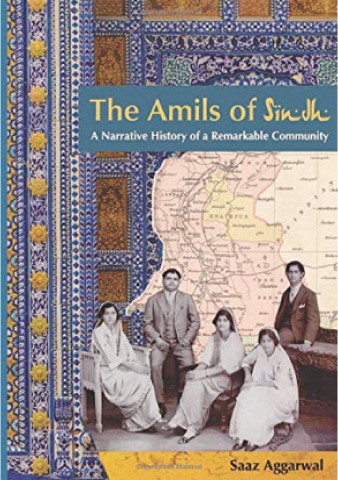

May 2019 saw the release of the book The Amils of Sindh: A Narrative History of a Remarkable Community, commissioned by the Khudabadi Amil Panchayat and penned by Saaz Aggarwal, the author of Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland. The book under review here lives up to its name, in the sense that a substantial portion of it consists of the oral narratives of numerous Amils (disclaimer: as an Amil, I, too, was interviewed for this book). Aggarwal has clearly put in considerable effort, interviewing numerous Amils in various walks of life and from many corners of the world. Although she has interviewed Amils of all ages, she has largely focused on the generation that migrated from Sindh.

Even though in public perception, the stereotype of a Sindhi Hindu is a money-minded businessman, Sindhi Hindus also include a sub-community who were traditionally professionals: bureaucrats, lawyers, doctors, engineers, writers, teachers and so on — collectively known as the Amils. According to some versions of community history, Khudabadi Amils were those who came as ministers of Mian Ghulam Shah Kalhoro first to Khudabad (near Dadu), and then to Hyderabad (in Sindh). They continued as ministers and bureaucrats under the Talpur rule. Subsequently, during the colonial period, the Amils came into their own, dominating education in Sindh as well as senior posts in the bureaucracy and courts of justice. Subsequently, after Partition, they used their education, skills and social contacts to successfully rebuild their lives and regain their socio-economic status, both in India and the diaspora.

A valuable addition to Sindh studies, a new book presents the history and oral narratives of a community largely displaced during Partition

The first section of the book, on the early history of the Amils leading up to Partition, is strong and informative, delving into the past of not just the Amils, but also Hyderabad and Sindh and delineating the crystallisation of Amil identity. It furnishes the reader with a plethora of fascinating details about the manner of dress, elaborate journeys, shops and houses in pre-Partition Sindh, among others.

The second and third parts, which cover Partition and the arduous process of resettlement and rehabilitation, are largely a collection of personal narratives. Although Aggarwal says that her aim has been to “present a wide range of facts, personal anecdotes and theories without any leaning or bias”, here one misses the author’s voice that had a robust presence earlier in the book. These sections bring out the stoicism, the resilience and the grace with which many of these Amils dealt with their trauma — as did other Sindhis. However, there are so many persons mentioned, and some without any introduction either, that the reader is sometimes left bewildered.

The book foregrounds the importance that Amils have given to education over the centuries, which has played a significant role not just in their culture and lifestyle, but also in their sense of self. Further, it goes on to break the stereotype of Amils as only professionals, and highlights other fields where Amils have excelled: business, the freedom struggle, the armed forces, sports, cinema and — while in Sindh — zamindari [landholding].

In this light, it is all the more surprising that, while Aggarwal has provided profiles of Amils in these diverse fields, she has included only either scant or no details of the lives and personalities of some of the Amil titans of Sindhi literature, such as Bherumal Meharchand Advani, Parmanand Mewaram and Jethmal Parsram Gulrajani to name a few, although she has written about others such as Dayaram Gidumal Shahani and Dr Hotchand Mulchand Gurbaxani. Similarly, there are hardly any details about the lives of senior political leaders such as Dr Choithram Gidwani, Jairamdas Doulatram and Professor Ghanshyamdas Jethanand Shivdasani.

Even though in public perception, the stereotype of a Sindhi Hindu is a money-minded businessman, Sindhi Hindus also include a sub-community who were traditionally professionals: bureaucrats, lawyers, doctors, engineers, writers, teachers and so on — collectively known as the Amils.

A very welcome section of the book explores the high degree of feminism among Amils. Amil women were among the best educated women in colonial Sindh, and I can personally attest that the tradition of education and freedom for Amil women continues even today. Another interesting section is about the various religious shrines founded by Amils, including those “transplanted”, or even founded afresh, in India after Partition. It brings out the diverse faiths of the Hindus of Sindh: many believe in Guru Nanak, while others are followers of the Ramakrishna Mission, various Hindu gods, the Radhasoami sect etc. Some readers may be surprised to know that several Amils were followers of Sufi pirs, notably Sain Qutub Shah of Hyderabad, and Sain Nasir Faqir Jalalani.

There are also numerous references to the legendary arrogance of the Amils, vis-à-vis not just Sindhi Muslims, or Hindus from other parts of Sindh, but even Hyderabadi Bhaibands, with whom they intermarried. Aggarwal also delves into the thorny question of the definition of a “true Amil”, providing many different points of view. The book closes with a short story which, although written by an Amil, has apparently little to do with Amils.

In all, this book is a valuable addition to Sindh studies. Amils will, in any case, be interested in reading their own history/ies, and, in the author’s own words, “It provides the context for present and future generations to identify themselves with pride in family grids to which they belong.” Further, like Lata Jagtiani’s book Sindhi Reflections: 140 Lives and the Indian Partition, it is also an important documentation of the experiences of the generation that lived through the tumultuous days of the 1940s, and will be of interest to other readers interested in this era of Sindhi history. Considering that this generation is on the wane, it is good to know that Aggarwal has announced that she intends to bring out similar books on other Sindhi Hindu sub-communities, such as the Bhaibands and the Shikarpuris. One can only hope to see more publications of similar oral histories of communities in Pakistan.

The reviewer is a Mumbai-based researcher and writer working on Sindhi history and culture. She is the author of The Making of Exile: Sindhi Hindus and the Partition of India and Sindhnamah

The Amils of Sindh: A Narrative History of a

Remarkable Community

By Saaz Aggarwal

Black-and-White Fountain, India

ISBN: 978-9383465088

732pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, September 15th, 2019

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.