Battling misinformation remains biggest challenge in Pakistan's fight to end polio

Syed Latif, a polio vaccination worker in Mansehra, has been working towards the eradication of the virus since 1994. Latif, who used to work in Karachi earlier as a vaccination worker and had also opened a secondary school in the city's Islamia Colony, was targeted by militants in 2012, which then led to his move to Mansehra. The attackers had believed that Latif was doing something “un-Islamic and immoral” in relation to his work on polio eradication and operating a co-education school.

Dawn.com spoke to Latif to understand how parents and caregivers are responding to vaccination drives and how can the rise in confirmed polio cases be explained.

Acknowledging that refusals to vaccination are happening, Latif says people are "scared of polio workers". He adds that while polio workers are on the frontlines, take on many risks, and have suffered in the line of duty, there is a lack of trust when it comes to convincing parents and caregivers that the vaccine is good for their child.

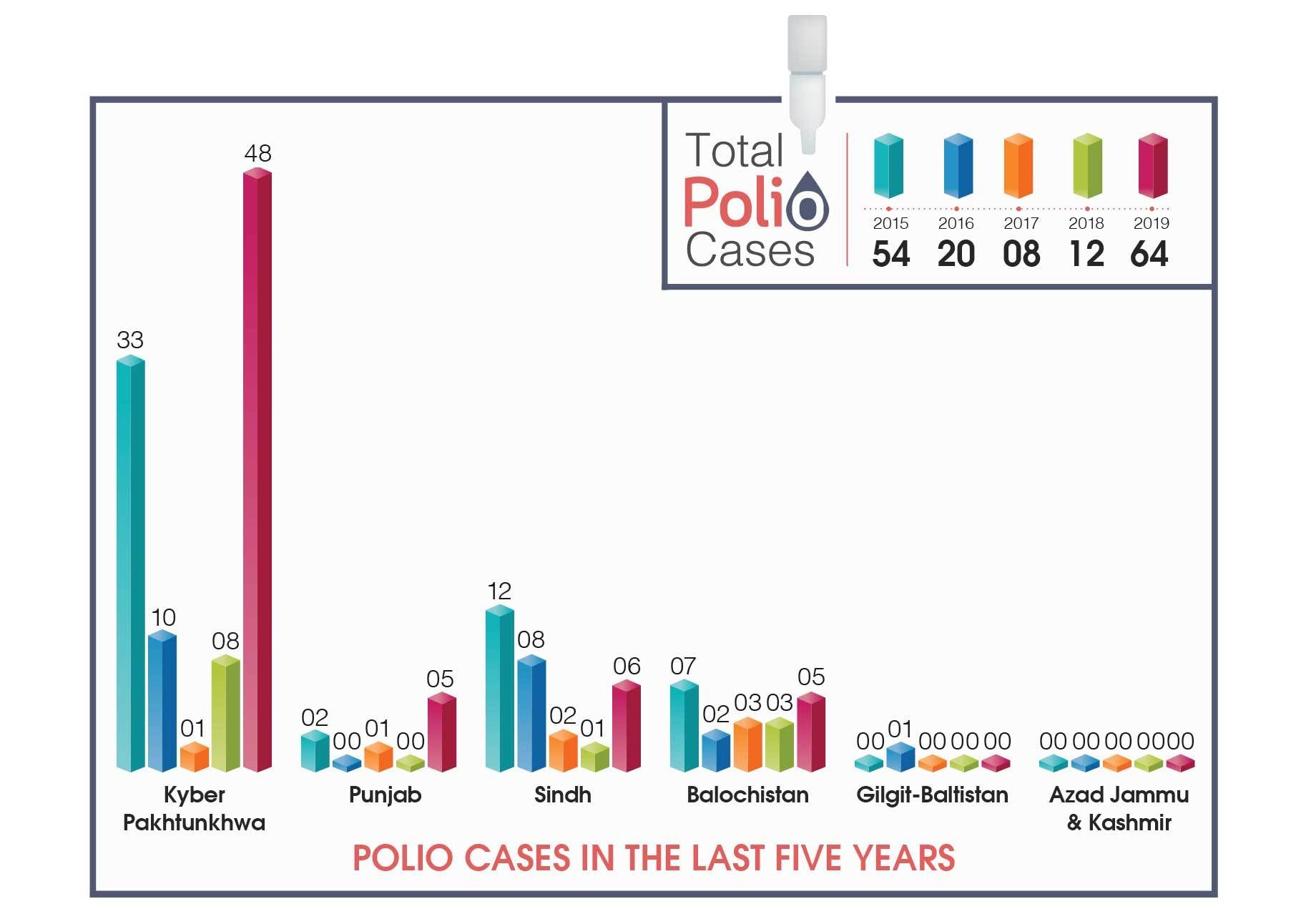

As the numbers of confirmed cases are rising, the Independent Monitoring Board is set to review on Tuesday Pakistan’s progress with respect to the country’s polio eradication efforts. As of now, the total number of confirmed cases for 2019 stand at 64 — 48 from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, five from Punjab, five from Balochistan, and six from Sindh.

Last year, only a total of 12 cases were confirmed in all of Pakistan.

This increase, according to many polio eradication officers operating on the ground, is because of a fake video that went viral in April 2019. The video showed a man shouting and claiming that the vaccine was harmful for children, with the camera cutting to a group young boys who act to faint on cue.

Although the man was arrested for spreading misinformation about the vaccine and the government issued multiple clarifications in days that followed, the video had managed to do quite a lot of damage.

Many polio workers who went on eradication campaigns after the video had been circulated said that people who normally had their children routinely vaccinated had become wary and afraid. And quite a few of these people, they said, had also reacted to the idea of vaccinating their children with aggression.

Tackling misinformation and fake news

According to the prime minister’s focal person on polio eradication, Babar bin Atta, the rise in polio cases is because "large numbers of children remain unvaccinated during campaign rounds".

"Rumours and propaganda spread over social media platforms have been fuelling misconceptions about the vaccine and have accelerated refusals to vaccines across the country.”

He adds that because children remain unvaccinated and there is also an increase in environmental positive samples, we see the spike in polio.

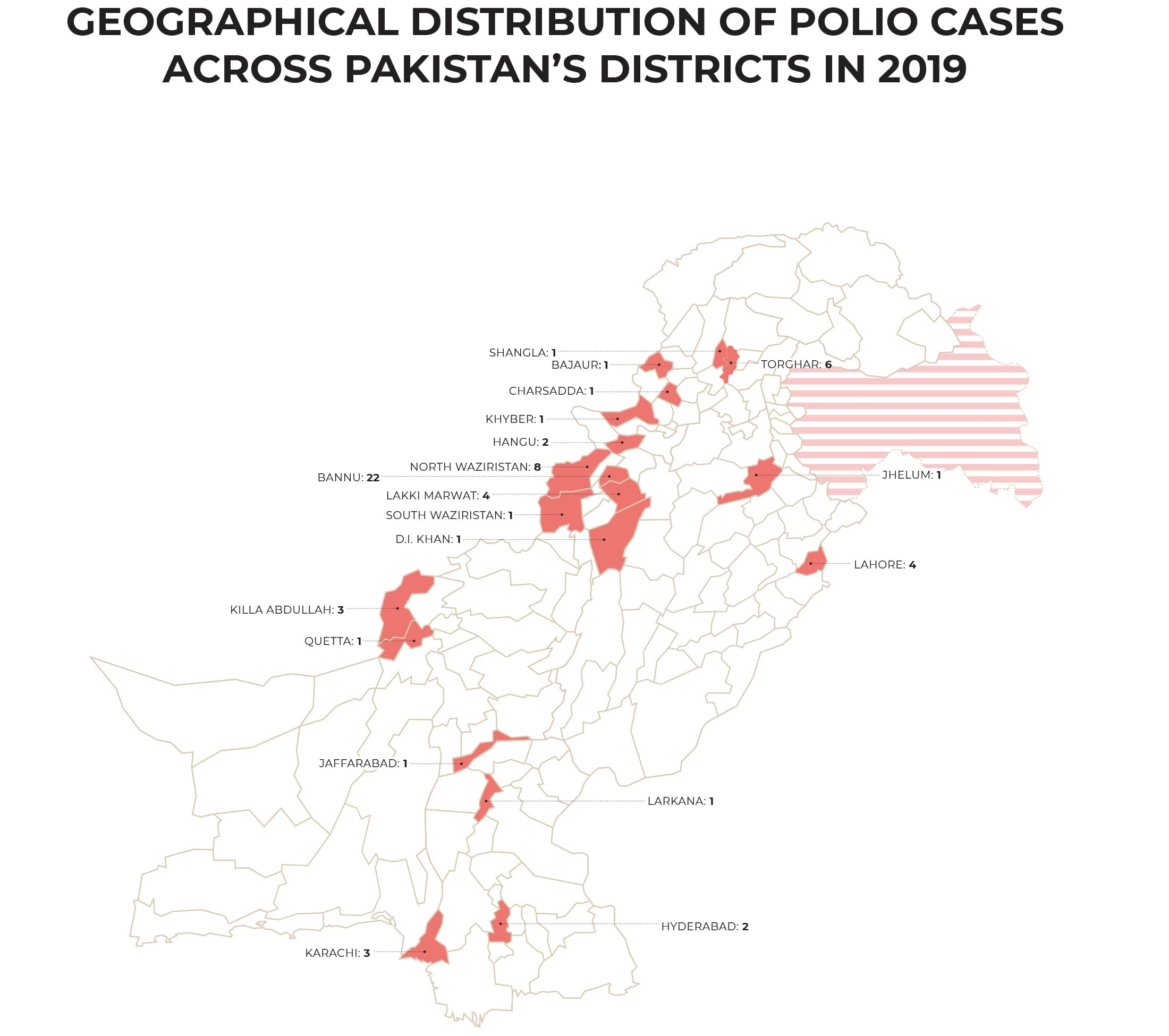

"Increase in polio cases directly correlates to an increase in environmental positive samples," Atta says, adding that "persistent virus transmission is happening across the country, even in areas that were previously not reporting circulation of the virus".

Asked how Pakistan can combat anti-polio vaccination propaganda, Atta says: “We are tackling the spread of misinformation and propaganda through active engagement with Facebook, and with the launch of the Perception Management Initiative, we expect major turnaround.

Also read: What's behind the alarming resurgence of polio cases in Pakistan?

"This is about turning the tide on negative perception against the polio eradication programme among resistant communities and ensuring they know the real risks to their child’s health, and the health of all Pakistani children.”

Situation on ground

With enough misconceptions and fake news going around that make it difficult for vaccination workers like Latif to do their duty smoothly during drives, another factor that makes the task tougher is the presence of security personnel with vaccination teams.

Latif points out that while security for polio workers is necessary, it also at times has been detrimental to the cause and increases distrust from parents and caregivers.

“Owing to the security situation, polio workers are often accompanied by police or Rangers personnel, which does not help us earn the people’s trust and has in fact made matters worse,” he says.

He adds that often it happens that people either do not answer the doorbell or would lie that they have no children in the home.

Latif says all of this can be tackled very easily.

He says: “We need the government to help strengthen facilitation centres. Why, let me explain, the last polio drive in Karachi's SITE town was carried out in June. Since then, the centre for the Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI) in Islamia Colony has received 15 to 20 children every day for administration of polio drops and routine vaccinations.”

However, with the current numbers, it is pertinent to ask, will enough people visit facilitation centres or are door-to-door drives still imperative?

Shameen, a polio worker in Karachi’s Korangi area, says she considers herself lucky since the vaccination drive she is a part of is working in her own neighbourhood where people know her on a personal level.

“When we started the vaccination campaign here, people were receptive. We still had refusals but at least we could discuss things with them, work on the families and eventually change their minds,” she tells Dawn.com.

“The union council that I work in is a high-risk area. Majority of the families here are Pakhtoon. They can be very difficult to convince.”

Speaking of some of the challenges she faces in the field, Shameen also brings up the fake video that Latif had earlier spoken about, saying it had made an already difficult job even tougher.

"This video came out while a campaign was ongoing. People were furious […] they were scared. They had relatives calling them from their villages in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, warning them against the vaccine and how it could kill their children,” she recalls.

This fake news video caused tremendous damage, Shameen says, adding that because of it the drive ended up with quite a few refusals "no matter how hard we tried to convince people to vaccinate their children against polio".

"They accused us of lying."

How the parents feel

Farooq, a resident of Lyari, says he gets his children vaccinated against polio like clockwork.

“We have six children in the house and everyone in our neighbourhood gets their children vaccinated in routine door-to-door drives. And if we have an issue, we ask the polio workers to show us the expiration date on the vaccine or to tell us more about it,” he says.

Farooq found the two women who came to vaccinate the children at his home trustworthy and is aware that quite a few times polio vaccination workers don't have it easy.

"They [vaccination workers] told me that if the vaccine wasn’t safe for their own children, they wouldn't give those two drops to mine and that made sense to me,” he says.

Meanwhile, Zia and his wife vaccinate their children regularly but they are not satisfied with how polio workers behave and conduct themselves.

“They come to our homes early in the morning. I have a sick mother at home and she gets disturbed. They don’t stop ringing the doorbell. My other issue with them is that our street is filthy; why do polio workers have to give the drops to our children near dirty water and garbage?”

Special report: Will Pakistan ever become polio free?

Zia adds, "I get my children vaccinated regularly. But recently when the campaigns were underway, polio workers forced the school that my children go to to vaccinate them, again and again.

"I understand this is important but does that mean that you bring the police or the magistrate to my house? If I am open to talk about these things and discuss them, then is this fair to us?”

A matter of national emergency

Despite the rising numbers of polio cases, Atta is certain that Pakistan will soon be polio-free.

“Ending polio in Pakistan is a top priority for this government. We see it as our responsibility to ensure polio eradication. But we cannot do it on our own.”

What the government needs now is for the people of Pakistan to join this mission, Atta adds.

“This is a matter of national urgency and we need the cooperation of parents, caregivers and citizens across Pakistan to ensure that any and all children are vaccinated against polio every time frontline workers visit."

Cover photo by Matiullah Achakzai, map design by Essa Taimur Malik and graph design by Leea Contractor