PAKISTAN’S ‘POSITIVE’ CRISIS

Over six months ago a massive HIV outbreak in Ratodero sent shockwaves around the country and internationally. Today, as World AIDS Day is celebrated across the globe with the theme ‘Communities, Make the Difference’, Eos looks at how the community in Ratodero is dealing with the aftermath of the outbreak and all the media attention that came with it

The newly set up ART (antiretroviral therapy) Centre in Taluka Headquarter Hospital is the only ‘fancy’ public place in the dusty, underdeveloped town of Ratodero or, for that matter, in most talukas of Larkana district. Staff at the ART Centre says locals suffering from everyday ailments often drop by this centre rather than going to the main hospital building. The centre seems fully functional and “looks like the hospitals they see on TV”, in stark contrast to the remaining ill-equipped hospital. The walls of centre have framed ICT (information communication technology) material from donor organisations including the World Health Organisation and UNAIDS. All this material is in English, a language which barely any visitor understands. Nonetheless, the framed information material adds to the relatively upscale feel of the place.

“It’s like a five-star [hotel] [were] set up in [a place like] Lyari,” says a resident of the taluka. “We are now known as the [HIV] positive taluka,” another local chimes in.

The centre is, of course, not the only reason the taluka is considered ‘HIV positive’. Residents of Ratodero town and nearby villages continue to grapple with the media attention following an outbreak in April this year, when an HIV-positive doctor was found to have spread the infection to dozens of patients by reusing syringes. The case made headlines and, eventually, led to steps like setting up of the ART Centre by the Sindh government.

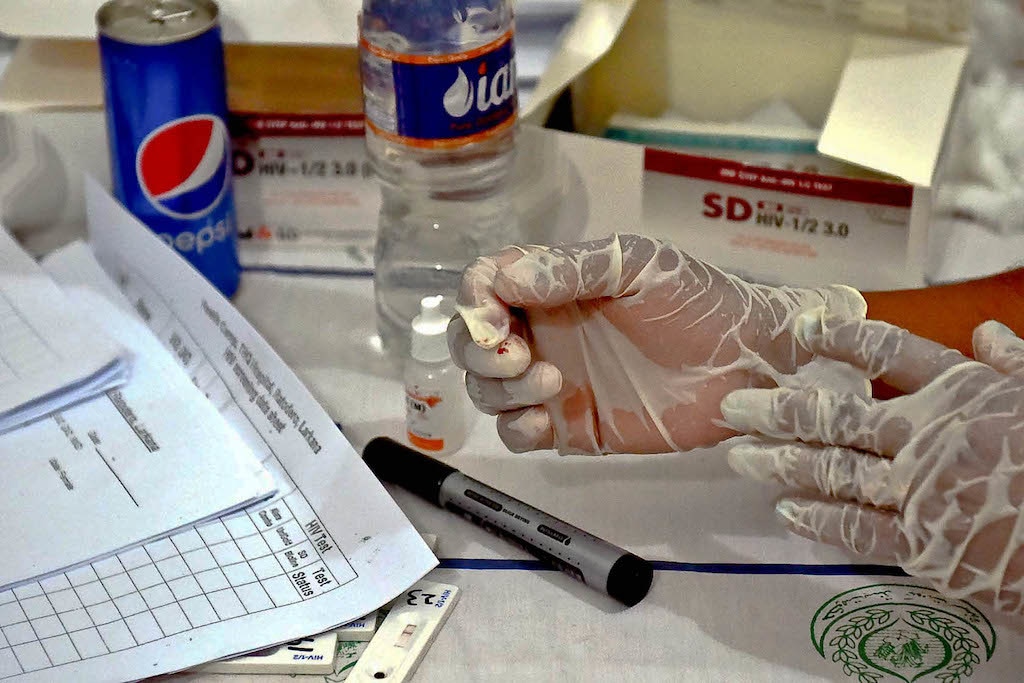

But the problem is bigger than the criminal negligence of one doctor. Investigations reveal poor infection control practices in the area and unsafe blood transfusions, with many victims stating that they never went to that particular doctor. As of November 19, 37,272 people have been screened for the virus. Of these, 895 are confirmed cases, with a shocking majority of the patients (754) being children. Another 1,181 were deemed suspected HIV cases.

Every few days, boys from Larkana and nearby districts make their way to see what “HIV waraan” (people with HIV) look like. Some even end up at the doorsteps of “positive families” since the details — names, addresses, test results — have been shared in local publications and social media.

Nazeer Hussain, the father of an HIV-positive child was instrumental in raising the issue of HIV in Ratodero on social media. Talking to Eos, he says things have gone from bad to worse. Others may consider the Art Centre a ‘five-star’ establishment, but Hussain is still unsatisfied with the quality of care. His daughter’s treatment is being carried out under the care of a doctor in Karachi. “The quality of care available here is very different,” Hussain says. “It’s true that ARVs are free, but who is going to ensure that these children have access to good food, education and companionship?”

Hussain has been vocal on the issue of HIV in Ratodero since April 23, around the time his daughter tested positive for the virus. The child had been sick for months and had been treated by the doctor — himself an HIV-positive individual — who reused syringes on women and children coming to his clinic.

The community here falls amongst the poorest of the poor in Pakistan. Before the outbreak, not many outside the high-risk group had even heard of HIV or knew that children could be at risk. Infectious diseases experts call the Ratodero outbreak “unprecedented” as it involved the general public, mostly young children, who do not fall under the high-risk group.

RATODERO’S POSITIVE FAMILIES — AND THEIR CHILDREN

Kiran* covers her face whenever she is walking into or out of the ART Centre. The young woman from Pano Aqil and two of her four young children are HIV-positive and are currently receiving treatment at the centre. “I don’t like the idea of people calling me and my kids names,” she says. Her father-in-law, who is accompanying her to the centre, tells Eos that people avoid contact with them. Kids refuse to play with even his older granddaughters, who are not infected.

Kiran, whose husband is also HIV-positive, is unsure how she was exposed to the virus. Doctors have told her she could have caught it from her husband or due to the blood transfusions she received during childbirth. Kiran seems to have no hope of things improving for her or her two HIV-positive children. Her father-in-law tries to reassure her, asking her to have faith in Allah.

But for these “positive families” it is difficult to imagine a brighter future.

The community here falls amongst the poorest of the poor in Pakistan. Before the outbreak, not many outside the high-risk group had even heard of HIV or knew that children could be at risk.

Seven-year-old Nida* was a happy school-going child not too long ago. She was blissfully unaware of the fact that, like her parents, she too is HIV-positive. Then one day a cousin of hers told a teacher and some students that Nida’s parents have AIDS. “The headmistress called me and asked if this were true,” says Aqeela*, the girl’s mother. Aqeela knew that her daughter was being bullied in school since she was outed and could not take it any longer. She sent her older children to her parents’ house in another city and opted to homeschool little Nida herself.

“Nida doesn’t know what is wrong with her or us,” says Aqeela, adding that she doesn’t allow her daughter to mingle with other kids. “I have no idea what will happen once she grows up,” she says, throwing her hands in the air in frustration.

Like Nida, other HIV-positive children or those with HIV-positive parents are also bullied at schools in Ratodero. “Many parents have asked the school authorities to remove these HIV-positive children or else they will take their kids out. There is too much hostility,” says a local.

Dr Imran Akbar Arbani, the whistleblower behind the Ratodero outbreak, says that whatever is happening in the town is just a reflection of attitudes in the country towards HIV-positive people. “These people are being rejected in society,” he says. “There is so much misinformation that people feel HIV can be transmitted by sharing utensils or just holding hands.”

Indeed, the problem of misinformation regarding HIV/AIDS is not specific to Ratodero. Partly owing to this misinformation, many HIV-positive persons around Pakistan live on the margins of society. The hundreds of HIV-positive children and families of Ratodero are still a minority. High-risk groups for HIV include injecting drug users (IDUs), transgender sex workers (TSWs), men who have sex with men (MSM) and female sex workers (FSWs). Migrant workers deported from Gulf countries — once their HIV-positive status is known — is yet another group along with prisoners. Then, there is the bridge population — including spouses, intimate partners and clients — who, through close proximity to high-risk groups, are at the risk of contracting HIV.

INJECTING DRUG USERS

The population of drug addicts in Pakistan was estimated at 113,400 in 2016, according to key population size estimates and the National AIDS Control Programme (NACP) data. With 21 percent HIV prevalence, barely 39 percent of IDUs know about their status, as per NACP’s ‘Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance in Pakistan’. NACP’s 2019 data further shows that there are 6,426 people who inject drugs and are on ARV therapy.

Shaheer* was an IDU and would often share needles before he found out he is HIV-positive. “It’s a battle every day not to relapse,” the young man from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa tells Eos. “I think about the high and then I think about the virus in my veins,” he says. “When you are high you don’t care if the needle is new or reused. It’s impossible to be sure.”

Shaheer was diagnosed in 2014. He had previously run away from home because his family wanted him to quit taking drugs. Once his diagnosis came, he was “too ashamed to let anyone know” about his status.

Even when a lab technician gave the young patient details of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Aids Control Programme, he was afraid of seeking help. “I was scared they would call my family,” he recalls.

A year-long bout of severe illness eventually forced him to reach the aids control programme. “The ARVs have changed my life,” he says now. While the young man has relapsed a few times, he is trying to stay clean. It has not been easy, of course. Money is short and being a high-school dropout means his chances of finding formal employment are limited. “I do whatever work I find,” he says.

Since his diagnosis, Shaheer’s IDU friends have shunned him. “I am sure some of them are positive but they don’t want to get tested,” he says. Other friends go as far as blaming him for their sickness. Shaheer’s relation with his family also remains strained. While he did not have the heart to tell his parents or sisters about his HIV status, he confided in his elder brothers. Instead of offering him support, they were furious at him. “They don’t want any contact with me,” a disappointed Shaheer tells Eos. “They refuse to hug me on Eid, fearing that I will pass the virus on to them.”

MISCONCEPTIONS GALORE

“There are some 1,200 transgender sex workers in Larkana district and out of these 100 are HIV-positive,” estimates Simran, a transwoman who works as an outreach officer at Pireh Male Health Society, a community-based organisation which creates awareness on male and trans issues. Simran has observed that most men who have HIV do not share their status with intimate partners. “They will be sleeping with their wives and their lovers but will stay mum and infect them,” she says. Sitting with Simran is Malika*, an HIV+ transwoman, who was a sex worker and an employee of the Revenue Department. Malika now works at Pireh. “I tested HIV-positive in 2015 and had no understanding of the infection,” she says. “I felt it was over for me but I did not inform anyone.” After continued illness, she finally started taking ARVs and has never looked back.

There has been a 369 percent increase in the number of AIDS-related deaths since 2010, from 1,400 deaths to 6,400 deaths. The number of new HIV infections has also risen, from 14,000 to 22,000 in the same period, UNAIDS notes.

Activists believe the culture of silence around sex makes matters worse, endangering sex workers and other marginalised communities alike.

“In most parts of Punjab, sex between men is an open secret,” says LGBTQ rights activist Hamza Rao. Based on his interactions with the LGBTQ community in the city, he believes the prevalence of depersonalised, spontaneous sexual encounters between men makes this group more prone to sexually transmitted diseases. “There’s a growing culture of dating and finding sexual partners via smartphone apps and that’s often not safe,” he says. “This puts a lot of lives at risk and the policy of silence leaves so many vulnerable.”

Activists agree that we need to cultivate an environment where HIV-positive individuals feel safe sharing their status.

A HISTORY OF INDISCRETION

HIV made its way to Pakistani consciousness in the mid-1980s, when Nazir Masih, an HIV-positive migrant worker was deported from UAE. Masih worked as a tailor in Dubai but was sent back to Lahore after testing positive for HIV. Nazir, labelled Patient Zero, was outed by reckless journalists in 1990 and became the much-demonised face of HIV/AIDS in Pakistan.

HIV was deemed a ‘sex disease’ and ‘buray logon ki beemari’ (the disease of bad people) — a reputation that sticks to date.

Rubina, a middle-aged woman from Punjab, contracted the infection from her husband who passed away before his illness could be diagnosed. After sharing suspicions that she may be HIV-positive, her doctor did the unthinkable and called and alerted her in-laws. She was kicked out of the house once her reports confirmed the doctor’s suspicion. Helpless and shelterless, she moved from one neighbourhood to another and eventually moved to another district.

Zohaib*, a vendor, from Balochistan, faced a similar ordeal. He got badly injured in a road accident and had to go to a hospital in Kashmore to get multiple blood transfusions. “A few months after the accident, I started to feel really sick,” he says. “I went to many doctors and then one finally ordered tests for HIV. I protested, telling him I never had sex outside of marriage.”

Zohaib felt a car had hit him once again when he found out he had HIV. “The toughest part was telling my wife,” he says. All hell broke loose. Zohaib’s wife accused him of infidelity and eventually left him. Unfortunately, the worst was still to come. “Her brothers came to the house and shouted threats. The entire neighbourhood found out I had HIV,” he says. He eventually left the province and moved to Multan, shunning all contact with his family. “With Facebook and Whatsapp around, I dread the day when news will reach here that I am HIV-positive and I will once again be forced to move,” he says.

People like Rubina and Zohaib, and even children like Nida, continue to look over their shoulders no matter where they are based. Such stories are a dime a dozen and will only continue to increase. A NACP report states that, as of 2018, Pakistan has an estimated 150,000 people living with HIV. “HIV modelling suggests that if the HIV epidemic continues to rise at the current pace the estimated number of [people living with HIV] will rise from an 177,000 in 2020 to 410,000 in 2030,” it goes on.

The document says that the growing HIV epidemic indicates that the national HIV response has been ineffective in halting the spread of the infection. “It also suggests that the scope, coverage and uptake of HIV preventive and treatment services is also not satisfactory.”

There has been a 369 percent increase in the number of AIDS-related deaths since 2010, from 1,400 deaths to 6,400 deaths. The number of new HIV infections has also risen, from 14,000 to 22,000 in the same period, UNAIDS notes.

NATIONAL RESPONSE

NACP head Dr Baseer Achakzai believes that the programme has “good outreach in key populations.” “So far, HIV is confined to high-risk groups only,” he says. But, he says, the media is not interested in helping his programme spread information. “I requested some 30 top anchors, journalists and media personalities to talk about HIV in their respective shows,” he says. “But with the exception of two or three anchors, who only spoke for two minutes at the most, none showed any interest.” The NACP is underfunded and running national-level print and electronic media campaigns means spending millions. “A half-page ad easily costs 13-15 lakh rupees. TV is way more expensive,” says Dr Achakzai.

Experts also call for advocacy and provision of reliable screening of donated blood, safe injection practices, safe delivery/surgery and safe sex. Reliable diagnostics and reliable supply of cheap and effective drugs are also incredibly important if we are to prevent the concentrated epidemic from evolving into a full-blown epidemic.

Every few months, the Senate and National Assembly grill him and his team about “not doing enough”, but they simply do not have the budget to do more. The NACP head says 260 million dollars are needed for support, operations and treatment. “Currently, the programme has 40 treatment facilities which need to be increased to 80 to ensure improved care,” he says. “We need to be able to ensure that treatment continues once The Global Fund leaves,” he adds.

On the subject of harm reduction, he says hospital waste disposal remains a major issue but that is for the health authorities to tackle. He stresses that there is a need for health care systems to make HIV screening part of routine check-ups and destigmatisation of the disease is needed.

The NACP has also introduced preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in which antiviral drugs are given to people in high-risk groups who have not been exposed to the disease yet.

Another step the government needs to take, Dr Achakzai suggests, is allowing opiate substitution therapy (OST) in the country. “Law enforcing agencies say OST will allow a new form of drugs in the country,” he says.

He challenges this perspective by pointing out that OST is a harm reduction initiative that offers drug users an alternative — methadone or buprenorphine — which is taken orally rather than intravenously. In many developed countries, this has successfully helped in reducing illicit opiate use, HIV risk behaviours, death from overdose, and improved mental wellbeing and reduced financial stresses. In neighbouring India, OST has successfully been part of public health policies and programmes since two successful pilots in 1999-2002 and 2006-07.

“The law-enforcement agencies need awareness. We are telling them that a proper registry would be maintained and the OST would be given away systematically and help fight HIV,” he adds.

Dr Afzal Zarkoon, head of the Balochistan Aids Control Programme and Dr Salim Khan of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Aids Control Programme agree that timely allocation of budget by the government remains a major issue. Yet another issue is keeping track of positive cases who often slip through the cracks due to poverty and discrimination.

RETHINKING OUTREACH

“There is a need to rethink outreach and awareness and act now,” says Dr Sharaf Ali Shah of Bridge Consultants Foundation, a not-for-profit which is sub-recipient of a grant by The Global Fund for AIDS, TB and Malaria. A former project director of the Sindh Aids Control Programme, he has seen the rise of HIV in Pakistan and acknowledges the need to create awareness among the general population and to “analyse communities and understand the dynamics at work.”

“There are towns and villages with many men moving abroad or to other cities for work,” he says. The women and children here are at risk and the strategy has to be different from those in poorer communities where there is next to no awareness about safe blood transfusions or reuse of injections. “There is a need for out of the box ideas for handling HIV.” Religious and cultural practices, as well as enhanced literacy rates, will improve the situation, he stresses.

Experts also call for advocacy and provision of reliable screening of donated blood, safe injection practices, safe delivery/surgery and safe sex. Reliable diagnostics and reliable supply of cheap and effective drugs are also incredibly important if we are to prevent the concentrated epidemic from evolving into a full-blown epidemic.

Talking to Eos, Dr Bushra Jamil, president of the Medical Microbiologists and Infectious Disease Society of Pakistan and head of Infectious Diseases at Aga Khan University, says “[Currently,] the onus is on the public to seek HIV screening and treatment. It should be the responsibility of healthcare facilities/providers to ensure voluntary counselling and testing.”

She also points out that there are no measures in place to protect those coming to the centres from stigmatisation. “As a result, many people who need treatment don’t go to such centres,” she says. “Infection control awareness is generally lacking throughout the healthcare system. Government hospitals, which cater to the needs of people from the lower socio-economic strata with high patient volume, have poor standards of infection control.” She notes that physician training for HIV is nonexistent. “Lack of familiarity [with HIV] makes quality of services suboptimal.”

The affected and the experts both say that protection and resilience is key in curbing the spread of HIV. Most importantly, there is a need to ensure that communities become an essential part of the healthcare system. The idea of supportive and caring communities needs to be fostered in Pakistan. Encouragingly, there has to be a massive sensitisation effort on the government’s part that takes into account physical, mental and sexual wellbeing of all citizens — including those with HIV.

There is a dire need to do away with the misconceptions and taboos surrounding HIV/AIDS and this calls for acknowledging the problem first. Lessons can be learnt from successful community interventions that took place locally and internationally along with new solutions. A good place to start would be Ratodero, where over 950 young HIV-positive Pakistanis need a specialised intervention that sets them on a path to healthier, happier lives and gives them a sense of belonging in a humane community.

*Name changed to protect privacy

The writer is a member of staff. She tweets @SumairaJajja