Long before the much-celebrated Latin American boom that is associated with the 1967 publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez — 32 years earlier to be precise — there was published in Buenos Aires a short novel titled La Ultima Niebla. Its author was a 25-year-old Chilean named María Luisa Bombal. According to a charming anecdote, she wrote the book at the kitchen table of an apartment she shared with a young and mostly unknown poet named Pablo Neruda and his wife when Neruda was working on his series of poems published as Residence on Earth. Both the writers were original and delightfully fresh, both with an imagination that glowed from the printed page. Neruda went on to acquire worldwide fame as one of the great poets of the 20th century; outside South America, Bombal’s fame is negligible and would be even less had some critics not remarked how her style anticipated the so-called magical realism of the Latin American boom.

And then, of course, there were the complications of being a woman writer. Virginia Woolf’s great feminist tract, A Room of One’s Own, had only been published six years before La Ultima Niebla, in 1929, and it would not be for another four decades before it would be taken up as a feminist manifesto. Woolf’s own most subtle, and one of her finest, novels, Between the Acts, would not be published till 1941 (and remain largely unknown to this day). It was hard enough to be a woman writer; much harder if you were intellectually advanced, as had been Woolf’s predecessors who had published under male pseudonyms — George Eliot and George Sand.

Their kind of singular imaginative bent expressing itself in a rich language catches the reader’s attention early in La Ultima Niebla, translated as The Final Mist, which appears as the first story in New Islands and Other Stories by María Luisa Bombal (translated by Richard and Lucia Cunningham, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1982). The matter-of-fact English of the title misses the poetic intensity of the Spanish original, and though the entire translation is indeed excellent, there are occasions when the English rendering deflates that intensity into sentimental banality, as in the sentence, “I feel as if I had fire in my veins”, for the English language is intolerant of abstract gestures. Despite this problem, which is inherent in any translation, the mysterious, imaginative dimension that sustains the structure of the story being presented in The Final Mist is what makes the work impressive. That vital projection comes through the story’s objective images, beginning with its first sentence, “The previous night’s storm had shaken loose the roof tiles of the old country house.”

The story itself is simple. The nameless young woman narrator has married her cousin Daniel and the two have just arrived at his house in his family’s old hacienda. A year earlier, Daniel had married a young girl whom he had adored, but she had died. Now, marrying the girl who was an inseparable playmate when they were children, he feels distant from her because his first wife is still alive in his mind. When they go to bed on their wedding night, he turns to his side and weeps; when she awakes in the morning, he has already left the bed and gone to the village, leaving her to confront silence and emptiness. Outside, “a fine mist hangs over the landscape like a veil.” Friends visit the couple, the men go hunting; whatever social life engages the narrator, she is still pained by finding herself in a silent emptiness surrounded by fog, even when she goes to the city. Life offers nothing but a futile repetition of meaningless events. She wanders out of the house in the city and there occurs the episode of her meeting a man who takes her to his house where they make love. For once, she is out of the fog and in a radiant world where she experiences rapture; but it all happens mysteriously and silently, and though the man becomes a vivid presence within her body, she will be tormented by never being certain of his real existence. In the following years, though her husband sleeps beside her “indifferent as a brother”, she discovers fulfilment in imagining that her lover of that one night is always with her, even coming to believe that he is physically present near her. Then come the surprises, leading in the middle of the story to her imagining that “the bedroom was submerged in a blue twilight in which the mirrors, shining like miniature lagoons, resembled those small pools of clear water reflecting sunlight in the Andes.”

In that one brilliant, precisely observed image, Bombal has taken her character out of the nebulous boring reality of daily existence and raised her to be among the mountain peaks where she glimpses a vision of her beautiful being. But the torment of her empty existence gnaws at her, her life “has been a charade performed in shadows”, she is “surrounded by a viscous spectral fog in which [her] very limbs float like disembodied objects”, and in that silent, empty world, her footsteps are like “sound waves on a cosmic journey, transmitting their mysterious message, this resonant staccato, to whoever listens among the stars.”

There is more dramatic action in the story, which by itself is the stuff of soap opera, but it is Bombal’s concentrated language with its cosmic imagery that takes the work to a metaphysical level and which turns a story of less than 50 pages to a large, memorable novel in the reader’s mind. As I’ve often said, language and imagery, formally organised in an original style, and not just the idea, is what makes literature. And this is what Bombal does in La Ultima Niebla.

Now it happened that 12 years later, in 1947, when she was living in Washington, DC, Bombal wrote in English a much longer version of La Ultima Niebla, which was published as House of Mist. And this is where Bombal goes quite wrong! Concentrating on the story, she fills nearly four times more pages than there are in the original with the kind of common sentimentality one sees in popular fiction; clichés permeate the dialogue-filled action, the narration is summarised and form follows formula, starting with a ‘Prologue’ that opens with what she probably thought was an original way to catch the reader, but is actually a familiar bait: “I wish to inform the reader that even though this is a mystery ...”, and then beginning the novel’s first chapter with, “The story I am about to tell is the story of my life.” The best one can say for House of Mist is that it would make a good television soap opera. It has all the conventional content that holds the attention of a mindless audience, surprising it with the obviously expected events, making a dialogue filled with banalities sound like profound wisdom, and leaving the audience with a happy ending just when it’s finishing munching its bucketful of popcorn. It’s sad that a desire for popular success sometimes misleads a gifted, intelligent writer — which Bombal certainly was — to fall for this approach.

Interesting to note, however, is that a year later, Bombal translated another of her successful novels, the prize-winning La Amortajada, which was published as The Shrouded Woman in 1948. Its basic form is not too promising: a dead woman in her unclosed coffin at her wake is watching a stream of mourners come to pay their respects, and the reader is taken into her mind where she gives an account of her relationship with each mourner when she was alive. One expects a series of flashbacks — that weary, hackneyed form favoured by popular novelists as an easy formula with which to tell a story. Bombal nearly falls for it, yet transcends it, and The Shrouded Woman is a fine example of how a potentially shallow work takes on profundity because of the quality of its language, inspired by the writer’s stubborn instinct to make an idea a forceful perception, infusing it with her original vision. Even the title bears that out. The woman is ‘shrouded’. It’s a central theme in Bombal’s work: the female condition, always to be covered, to be suppressed.

There is an amazing paragraph beginning with the brilliant metaphor, “There are unfortunate women buried, lost in cemeteries ...”, which contains a striking image of women who commit suicide by jumping into rivers — “whom the current incessantly beats over, gnaws, disfigures and beats over again” — which is a poignant metaphorical projection of the condition of women and by implication makes a strong statement of feminist thought.

In fact, the substance of feminist thought at the heart of the feminist liberation movement of nearly 40 years later is vividly expressed in Bombal’s fictions written in the mid-1930s. Furthermore, the best of them contain that intense metaphorical language with which to depict ordinary reality which is the essential element of literature that keeps it alive in the reader’s mind. And she goes beyond her contemporaries, including Woolf, when describing sexuality; indeed, some passages are so erotically vivid, and charmingly beautiful without a hint of pornographic voyeurism, they would have won the applause, and perhaps even the envy, of D.H. Lawrence and Vladimir Nabokov.

There is magic in the best of her work — not magical realism, that absurd label supposedly bestowing distinctive originality on writers associated with the Latin American ‘boom’, as if Francois Rabelais, Miguel de Cervantes and William Shakespeare had never existed. The magic in the prose of Bombal’s best work — the two long stories The Final Mist and New Islands, and the novel The Shrouded Woman — is the magic of the creative imagination that has distinguished all the great writers: it is in the lighthouse gleam thrown out by the images that hits the reader’s mind and there becomes an internal illumination, with nothing stated and nothing understood, but an explosive metaphysical thought experienced.

Then, for what it’s worth, there’s this historical consideration: as women writers, the two Latin Americans — María Luisa Bombal and Clarice Lispector — ought to be known as two of the best and, for the sheer quality of their writing, as far superior to such mediocre nonentities as Doris Lessing and Nadine Gordimer, whose reputations come from being elevated by readers who are flattered that their own simplistic worldview coincides with their subject matter and by professors for whom literary criticism is little more than a portentously worded statement about a work’s relationship with the sociopolitical context of its time. That said, as we come to the second decade of the 21st century, however, any segregation should be an irrelevance and the writer’s sex, nationality, political stance or association with some dominant trend of one’s time should be of no account in our evaluation of a writer’s worth.

But sadly, though knowledge and experience should have liberated us by now from all tyrannies, our understanding has become narrowed not only by the academic abandonment of the aesthetic conception of art in favour of its serving some social cause, but more viciously by the worldwide hooliganism of religious repression with its intolerance of education, and by the manipulated election of barbarians as the world’s leaders. They will never know the mysterious vision that comes to an artist such as Bombal as a “rage for order” in the chaos one experiences as existence, like in her story New Islands in which she projects an insight into existence through images that show the planet Earth in a turmoil of constant change while in its still centre we are shown, through the eyes of an amazed male who, seeing the woman he loves standing naked in her bedroom, observes something curious growing on her right shoulder: a wing. But it is only “the stump of a wing”, a “small atrophied member”, and only on one side of her shoulder. This is writing that explains nothing; no meaning is to be interpreted, but one feels a shiver in one’s flesh.

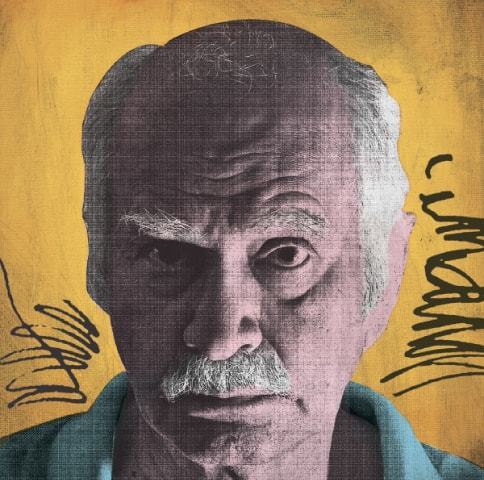

The columnist is a poet, novelist, literary critic and Professor emeritus at the University of Texas. His works include the novel The Murder of Aziz Khan and a collection of short fictions, Veronica and the Góngora Passion

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, December 29th, 2019

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.