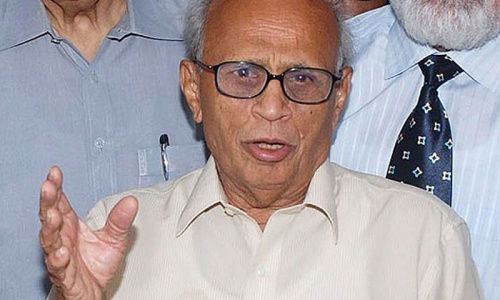

Retired Justice Fakhruddin G. Ebrahim has breathed his last after an eventful life. He is survived by a widow and four children, as well as a nation which turned to him time and again during trial and tribulation.

It’s a testament to his dedication and conscience that most of Justice Fakhruddin’s professional life was spent serving Pakistan. He served as a judge of the Supreme Court and the High Court, governor of Sindh, attorney general for Pakistan, federal law minister and chief election commissioner. Despite such a stellar career, Justice Fakhruddin, or Fakhru Bhai as he was affectionately called, was an embodiment of honesty and humility. He always said of his first passion, law practice, that “law is a bottomless, fathomless pit. You never stop learning”.

He never mentioned his appointments to public office, each of his resignations on grounds of principle, the victories in the courtroom or the praise that came his way. Whenever he was asked to share some of his experiences whilst he served in these positions, the conversation would inevitably turn to questions about the country and its people.

His obsession for Pakistan was a recurring theme throughout his life.

As a lawyer, Fakhru Bhai fearlessly represented labourers and workers, illegally detained prisoners and leaders of religious minorities. One instance he fondly remembered was when he represented an Ahmadi family which had allegedly pretended to be Muslim.

He recalled that when the rival counsel argued that the family had passed itself off as Muslim at the time of getting their wedding cards printed, he (Mr Ebrahim) replied: “Abay tu nay unka kaleja khol kay dekha hai kia?” (Have you peeped inside their hearts?).

He consistently maintained that his most memorable years were on the bench. He used to argue that there was no better job in the world than having the responsibility of solving people’s problems.

But this responsibility was cut short with the imposition of martial law by General Ziaul Haq in 1977. Fakhruddin Sahib would recall the infamous day with remarkable clarity: “We were asked by the Chief Justice to gather in a room. Since I was the most junior judge, the CJ first asked me ‘Fakhruddin Sahib, will you take oath under the PCO?’ I immediately replied ‘I’m going home, Sir’. After that he went around the table and one by one all the other judges agreed to take oath.

“Then I started thinking to myself, ‘Aray yeh to sub agree kar rahay hain’ (they all have agreed to take oath) and decided to walk over to my friend, Justice Dorab Patel, to ask him what he was going to do. After Dorab Patel confirmed that he too would not be taking oath, I breathed a sigh of relief.”

Fakhruddin Sahib would always narrate this story and heap praise on Justice Dorab Patel for his refusal to take oath under the PCO.

In doing so, Fakhruddin Ebrahim would never boast that he was the first person in this country’s history to stand by his constitutional oath and refuse to bow to the pressure of a military regime. That was classic Fakhru Bhai.

This “I’m going home” business happened time and again throughout his career. After having established the Citizens-Police Liaison Committee, he deemed it necessary to resign as Sindh governor when Benazir Bhutto’s government was dismissed in 1990. He quit the post of attorney general when the government engaged another counsel for a case without his knowledge.

As law minister, he went too far for the elite’s liking in pushing for transparency. He had only recently drafted Pakistan’s first-ever Freedom of Information Bill and called time when the government opposed his proposal to amend an election law provision which would have required a candidate to disclose his family’s business interests.

His simplicity and purity of heart were unbelievable. Whenever he was pressed to recall his decisions to quit such key positions, he would find the thought perplexing that these must have been difficult decisions. For him, it was always straightforward: “What is there to choose apart from truth and fairness.”

When his appointment as chief election commissioner was met with enthusiastic approval by political parties and the nation, he observed disarmingly that expectations from him were too great.

There can be no bigger testament to the respect he earned in his lifetime than the fact that our squabbling political parties agreed on one individual to oversee the 2013 general election. Many people told him that, in hindsight, he shouldn’t have accepted the chief election commissioner’s job. His impeccable reputation had been muddied for political point-scoring. But Fakhruddin Sahib just wouldn’t get it. He had put his reputation on the line for the future of this country and would do so again.

With his passing away, Pakistan has lost its proverbial trusted compass. Fakhruddin Sahib would find these words discomforting as he invariably flinched at praise. He was always at a loss for words, only managing a meek smile and a mumbled reply. Obsessed with spreading joy and peace, he would hate to see anyone mourn his death.

But let us celebrate his life nevertheless, albeit at the risk of irking him in the heavens. His years on earth were a tribute to the power of truth and fearlessness in our troubled world. For this, and your time with us, thank you, Fakhru Bhai. We are forever indebted.

Published in Dawn, January 8th, 2020