I have been in Duraid Qureshi’s Hum Television Network office many times before, but never was it this teeming with excitement.

Three photographers, two from Dawn, are moving small furniture around, posing Qureshi with bits of it, as they compose and snap picture after picture. Two videographers are standing idly behind me, their hands on their cameras and portable lights, unsure of whether they are done with their shooting or not (I think they are).

An executive of the network paces around just outside the office, fending off one phone call after another. Even Qureshi’s phone, which buzzes every five minutes, craves attention. Meetings are shifted by half-hour margins, making brief wiggle-room for last minute appointments.

There is a reason for the hubbub: the Hum Network is turning 15, and its CEO — Qureshi — has a lot to take care of.

“Why is all of your stuff so last minute?” I joke, as our unmade teas are slid in front of us on the table.

Although they may sound last minute, projects such as the Hum Style Awards, which will coincide with the anniversary next month, are cooked silently and then suddenly unleashed on the press.

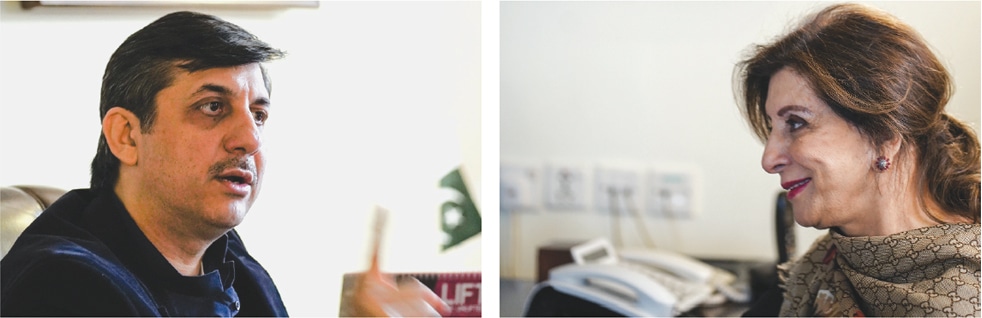

As the Hum Network turns 15, Icon reaches out to the driving forces behind it — the mother-son duo of President Sultana Siddiqui and CEO Duraid Qureshi — to find out what it takes to run a growing media empire

“We do let everyone in the press know a few days before, don’t we?” Qureshi says, retaliating with a wink and a nudge, knowing full well that this is how the media industry works.

As one of the pioneers in private television, Hum Network is often known to go big. Qureshi says there is no choice. I think he just likes it that way. Celebrating achievements and giving people — and the industry — the pomp and grandeur it deserves.

A business graduate of Lums (where he met his wife, Momina Duraid — one of the biggest producers in television), Qureshi is by far one of the most enthusiastic CEOs in the media business. Both a voice of reason (“the buck for decision-making stops at me,” he says) and an unyielding supporter of his network’s endeavours, he is almost single-handedly responsible for nurturing the idea of making a television network out of scratch.

The long story, which Qureshi narrates in the absence of his mother and Hum Network President Sultana Siddiqui, goes something like this:

As a fresh graduate from business school, Qureshi was brimming with excitement. His heart, though, wasn’t contented when he joined the sugar mill business. Growing up on PTV sets (where his mother was a producer), he realised the potential of the media business at an early stage.

It was a new time for PTV when he joined his mother’s production company. The channel had just started leasing time slots out to independent producers, who were producing and then getting the sponsorships for their own serials.

Learning on the job, Qureshi knew that because of his mother, one of the most sought-after producers in the field, he had an advantage over others. He didn’t have to wait in line to do business with the giants in the field.

“It was embarrassing at times,” he says, recalling an occasion. “There was a veteran director waiting to meet an executive of a media company for over an hour. However, the moment I entered, I was shown inside.” When he met the executive, the latter told him that he couldn’t let Qureshi wait since he was a close acquaintance.

The revelation of his standing stung deep. Qureshi realised at that very moment that, irrespective of the embarrassment he felt in front of the veteran director, he had the opportunity to learn things that others could only get from years of experience.

And so he throttled the gears, learning the ropes of the business at blazing speed, strategising solutions on the go. It would all come in handy soon in the early 2000s.

At the dawn of independent satellite channels, Sultana Siddiqui was given an opportunity to manage an up-and-coming television network. “It’s a job only you can do,” one of the principal owners of the company making the offer insisted.

Qureshi had a better idea. “Let’s start our own channel,” he told his mother. His reason was simple: he knew the owners, with no media experience of their own, would be learning on the job. Qureshi felt his position was better, because he and his team came with actual production and management experience.

“My [primary] reason was simpler,” Qureshi adds to the story. “I didn’t want my mum to work under someone else. She didn’t deserve that.”

The mother and son have always been close. One of the reasons he joined her line of work was to be close to her — though, I suspect, he likes the creative challenges of the medium more than he likes to admit.

“Hum literally started in the garage of our Bath Island house in Karachi,” he says, which he and his team, including wife Momina (who was handling the accounting of the business at the time), restructured in a matter of days.

“It was always about transparency,” he says, as he ambitiously registered the company in the stock exchange. “It made business sense, and that is the way it’s done the world over.

“From day one, it was my dream to not just make Hum a public-listed company, but to make sure that it has a life [and a distinct identity] of its own. One that empowers women, creates a culture that encourages growth, and is recognised in the industry for its professional practises.”

Although the flow of capital would help them eventually create an empire, it wasn’t easy sailings in the beginning. In just a few months after inception, the channel was struggling financially because the money that advertisers owed them hadn’t yet made its way back to the company.

Slashing salaries of key executives didn’t change anything, but rather than ask for money (“Once you do that, it’s all over,” Qureshi says) the company leased its assets, survived and turned up a profit a few months later.

“There was no looking back after that,” he says. The network grew naturally, adding fashion (Style 360), food (Masala), news (Hum News), print (Newsline, Glam and Masala magazines) and digital consumer assets (Hum Mart) to its portfolio.

Masala, inspired by BBC Food, Qureshi tells Icon, is the first food channel in South Asia; even India hadn’t come up with the idea at the time. Like everything, it was a spontaneous decision, and one of the many risks they took.

Style 360, which began as a small cable channel, went on air and created waves… but at great cost. Style 360 was in constant deficit, costing the channel some 660 million rupees during its five-yearrun, Qureshi tells me.

It wasn’t the only failed endeavour. Qureshi shows me the sketch of a logo with the face of a devil that read “Oye”. It was for a youth-based channel focusing on music. Unfortunately, it, and their radio networks (also a risk investment) didn’t turn a profit.

Qureshi, with a show of a heavy heart, says he doesn’t have a problem shutting businesses down if need be.

“As a public-listed company, I’m answerable to my board and to my shareholders,” he says.

What about Hum News, I ask, knowing full well that the recent channel was launched at an inopportune moment, when the ratings and the business of news channels were at an all-time low.

From day one, it was my dream to not just make Hum a public-listed company, but to make sure that it has a life [and a distinct identity] of its own. One that empowers women, creates a culture that encourages growth, and is recognised in the industry for its professional practices,” says Duraid Qureshi.

“The idea of adding a news channel in the mix goes back four years. If you remember, news was all the rage back then.” Still, Qureshi wasn’t mad about the idea. “It all came down to what my mum wanted,” he says, gesturing towards Sultana Siddiqui who has come into the room a little while ago.

“It was important to complete the bouquet [ie. portfolio],” Siddiqui adds as an explanation. This is the first time she has spoken.

One immediately sees the power Siddiqui holds over the company, and how far-sighted she really is. Launching and maintaining a news channel isn’t in Hum Network’s realm of expertise, yet in this day and age it seems like a necessity.

“People feel that the network has suffered because of the news channel. [But] the news channel was a planned entity and the loss is because of the state of the economy, rather than [because of us] entering the news genre,” says Qureshi. “In times of economic downturn there are opportunities. We’ve had major improvements and efficiencies in our systems [since we launched], we’ve cut down a lot of fat in our payrolls. [Still], we’ve not reduced, but increased our work, be it news or entertainment.” Qureshi would obviously rather focus on the positive.

“One sector where we haven’t seen a slump is digital, which has grown at tremendous speed,” he adds. “I see 2020 as a great year, especially by its mid.”

Our conversation moves on to the industry-wide acceptance of Hum being a family-controlled business.

“People may think that Hum Network is a family business, but it’s actually not,” Qureshi avers. “It’s true that my mum is the President, and that I’m the founding CEO of the company, and that my wife [Momina Duraid], [and his sister-in-law Moomal Shunaid] is doing productions for Hum. However, all of this is more of a coincidence. [Rather], it’s about individuals and their capabilities.” It’s always nice to find the most capable people in your own family, I think but don’t say.

The closeness of having a family-run business also has its strengths, he adds, perhaps anticipating the thought in my head.

“Working with one’s mum, it’s very easy and faster to explain one’s thoughts, and many of the times it’s just a matter of [reading the other’s] brainwaves. She understands what I’m saying, and there is a lot of trust, and that helps in many ways.”

What about going big, especially in this state of economy, I ask?

“Cutting corners on content should not be the goal. In such trying times, if we were to give our viewers content that is not entertaining, or is not on a grand scale, like the Hum Awards, [then] what’s the point?

“The awards [for example] is a big project which we do globally. We did the show in Houston last year, and before that it was in Toronto, Dubai, and now in the coming year [we are set to do it] in the UK,” Qureshi says. If anything, it creates opportunities for and awareness of Pakistani media globally.

“With every passing day, you can’t just keep on doing what you imagined [when you began],” he adds. “You have a new dream, a new vision and a new plan. You can’t just sit idly by,” Qureshi says as he is interrupted for the third time. His other meetings long overdue, he finally leaves me with his mother.

The first thing Siddiqui assures me after Qureshi’s departure, is that her son isn’t all business. “His creativity is at par with the best of them,” she says.

We start out discussing the responsibilities of the network — Siddiqui is literally the face of Hum. I feel that, after 15 years, Siddiqui is ready for more philanthropic endeavours. For her, like Qureshi, it is about the bigger picture… it’s just that her picture is a tad different than that of her son’s.

“I had begged the board to let me have a year for myself, so that I could start KFS [Karachi Film Society] and PIFF [Pakistan International Film Festival]. It’s all about the next generation and what we give them,” she says.

“The more we cultivate talent, the more the industry thrives, and that eventually helps Hum as well.”

It’s well-known that Siddiqui supports, and at times, has a say on most productions happening in Hum TV.

“I wouldn’t say [that I have a say] in every programme or drama. I only look into subjects that are taboo, or I feel need to be talked about,” she tells Icon.

This is also one of the principal philosophies of the network she tells me as we discuss the development process of their concepts. The channel has stricter creative control, with most productions made in-house than commissioned.

“We often look into relevant social issues that are affecting the people, and then we try to build a story around that. But [first and foremost], it has to be entertaining,” Siddiqui clarifies. I wonder what she thinks about the criticism that Hum’s dramas only cater to housewives.

“The stories we try to tell always empower women, whether they are housewives in lower, middle or high society classes,” she affirms.

“Entertainment should target women — and why shouldn’t it? Housewives, or working women, have very few avenues of entertainment. Men have many. Dramas should do that, as should films,” she declares with conviction, as if it is still a cause worth fighting for — 90 percent of productions already do target women.

“And it’s not just about catering to women. I meet men who often tell me that my dramas have made their lives hell, because women in their house tune into our shows.” In time, Siddiqui says, these same men come over and tell her that they’ve stopped watching news, which is headache inducing, and are happily watching the serials produced by her network.

In the years since this writer has known her, Siddiqui prefers entertainment over art-house projects. However, she acknowledges the need for diversification — especially when it comes to film. (TV is a far more by-the-book practice as far as storytelling is concerned, Qureshi had said to me earlier.)

“There is also a difference in taste”, Siddiqui says as we talk about the drama-ish style of Hum’s two feature films, Bin Roye and Superstar. “There are people who prefer Laal Kabootar, and then there are those who prefer Bin Roye,” she says.

Both films did make money, despite the challenging times they released in. At the time of Bin Roye, there were fewer cinema screens. At Superstar’s time, the economy was struggling — yet they were both hits, she had told me once.

Hasn’t the network slipped in the ratings game however, I ask Siddiqui. For years, Hum was considered difficult to beat. This conversation has come up many times in the past two months, often without satisfactory answers from both Qureshi and Siddiqui. In fact, they appear to be just as baffled by the revelation.

“The way ratings work is different than what we see and hear [from people] in real life”, she sighs. “If you look at the ratings from PTCL [which collects and shares data from their subscribers], we are double, at times three times, above the competition. Sources from where we get live ratings show different results than others [such as MediaLogic, a bona fide source approved by PEMRA]. Out of the three [ratings aggregators], if one is showing us at a disadvantage, then that leaves us bewildered as well.”

“I won’t pine like a bad student, who complains that they didn’t get high marks because the teacher was bad. Every quarter brings its own challenges, one quarter is bad, and one isn’t,” she rationalises, adding that advertisers wouldn’t be paying premium rates if the channel was suffering.

An established director and producer, I ask why Siddiqui has only directed one serial in the last 15 years at Hum.

“Truthfully, I was always a little afraid of directing again. First of all, I was out of practice, and understanding new technology and how it works took some getting used to. Also, the younger generation, who know all of this, are doing impressive work on their own,” she says.

“The network was also relatively new at the time, so a lot of executive managerial work required my attention as well. I knew that I couldn’t do justice to both direction and management at the same time.

“I was actually more than a little angry during the production [of her lone serial in the last 15 years]. When I was thinking on how to do scenes, there would always be someone from the office standing over me with a palanda [stack] of papers that needed to be signed.

“I knew at the time — as I still do today — that I didn’t need to make a name for myself. It was always about taking the network to a higher pedestal.

“I always tell [my son] to be cautious, even when taking risks,” she adds. “When one makes his way on top of a mountain, one should even be afraid of a single pebble. If that pebble makes you slip, then you tumble all the way down.”

The detail-oriented philosophy can only help Hum as it ventures onwards to the next 15 years.

Published in Dawn, ICON, January 19th, 2020