THE smell of rot in the state can be detected from a long distance. The communication gap between Pakistani rulers and the ruled continues to widen. The former claim the process of national decline has been reversed; the latter maintain the country is sinking deeper into the abyss of poverty, lawlessness and despair.

It seems the people are suffering because of five capital curses that are affecting their lives, their thoughts and their conduct: intolerance, hypocrisy, selective memory, premium on nonsense and the culture of obedience.

Some days ago, the Multan District Bar Association issued a press release regarding a resolution adopted by the Tahaffuz Khatme Nabuwat conference organised by it. According to the resolution, read out by Syed Athar Shah Bukhari, former Multan High Court Bar Association president, no non-Muslims, including “Qadianis”, will be allowed to take part in the district bar elections. The candidates will be obliged to file an affidavit about their being Muslim. The government did not repudiate this uncalled-for assault on the rule of law and basic rights. Even if it didn’t agree with the resolution it was probably afraid of taking on the preachers of intolerance.

The intolerance displayed by the Multan Bar office-bearers has been manifesting itself in various forms.

Multan appears to have drifted further away from the legacy of the saints Bahauddin Zakariya and Shah Rukn-i-Alam since the day three years ago when advocate Bukhari had the courage to lead the funeral prayers for fellow advocate, Rashid Rehman Khan, the outstanding human rights activist, who had been assassinated for defending Junaid Hafeez, the victim of an intrigue by a vigilante group in the Bahauddin Zakariya University.

Multan has always been proud of its religious seminaries and conservative clerics but it has also been proud of its tolerance of religious differences, and especially of its soft language of discourse. That the city should have been captured by denigrators of its hallowed traditions is a matter of concern for the whole country.

But the streak of intolerance demonstrated by the Multan Bar office-bearers has been manifesting itself in various forms across the country. The Council of Pakistan Newspaper Editors has been compelled to abandon its tradition of cautious dissent and protest forthrightly against the growing intolerance of freedom of expression. Indeed, newspaper editors are not the only people whose rights are under attack.

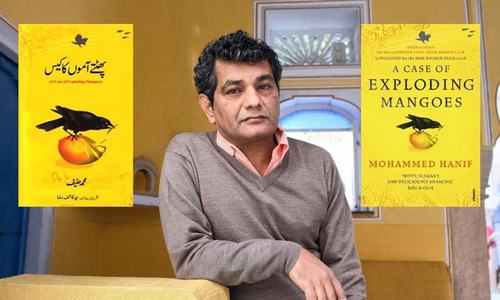

The Urdu translation of Mohammad Hanif’s best-selling novel (for 11 years), A Case of Exploding Mangoes, has been confiscated in a display of wanton malevolence. Intolerance is the only reason for stigmatising a tribal people’s peaceful movement for their rights. The same is the reason for preventing the courageous human rights defender Jalila Haider from going abroad and holding her in illegal detention for seven to eight hours, and for leaving filmmaker Sarmad Khoosat at the mercy of extremists. Many other examples of intolerance can be cited. And worst of all, those in authority seem to be blissfully unaware of the threat that the rising tide of intolerance poses to whatever good is left in our society.

To an extent the growth of intolerance is facilitated by an increase in the dependence on hypocrisy, which is evident, for instance, in the denunciation of political arrangements as ‘deals’. The slogan ‘no deal whatsoever’ is heard day in and day out. Even a child studying civics will tell you that all coalitions formed to enjoy power are based on deals. Some of the deals are in the form of pledges written in black and white. Aren’t concessions offered to businessman and bureaucrats to protect them against NAB’s excesses, real or imagined, based on deals? Does anyone who matters realise the consequences of taking irrational liberties with the political vocabulary?

That hypocrisy draws upon what may be described as selective memory can easily be shown. Two instances are sufficient to explain how selective memory is used to cover up political waywardness. For the serious energy crisis, the past governments of the PML-N and PPP are blamed and to some extent correctly but, without acknowledging whatever efforts they did make to meet the energy shortage. In contrast, there is a strong tendency to avoid recalling the role of the Ziaul Haq regime, more than a decade of it, in laying the foundations of the energy crisis. Will recalling the Zia regime’s failure to add a watt of electricity to the national grid and making Wapda an idle witness of growing problems take the sting out of attacks on political rivals?

The second example of selective memory is the hullabaloo over the atta price/availability scandal. All kinds of explanations have been offered and scapegoats discovered among the ‘others’, but nobody in authority is talking about the criminal export/smuggling of flour for three days and the billions of rupees made by the ‘good’ mafia.

One known method of blocking citizens’ participation in the discourse on governance, that is their right, is to lower the level of the debate by putting a premium on nonsense or vulgarity. One honourable minister is reported to have attributed the atta shortage to overeating by the people in the winter months and another has forced fellow discussants to leave a talk show by putting a jackboot on the table and thus clinching the argument. And there were no signs of the rage or anguish of the kind such outrageous antics demanded.

All these things are tolerated by the people largely because of their culture of obedience. They may not have read anything written by Ghazali but they are the most ardent followers of his dictum that a bad government is better than no government. Ordinary citizens choose to remain silent out of fear of punishment or the risk of a change for the worse. The peasants of southern Punjab, for instance, have been starving for two centuries but they have neither the will to change their vocation nor the strength to call the zamindars or their protectors to account. This culture of obedience is the most lethal weapon in the hands of oppressors.

Who will rid the people of Pakistan of the capital curses listed here? No one except they themselves.

Published in Dawn, January 23rd, 2020