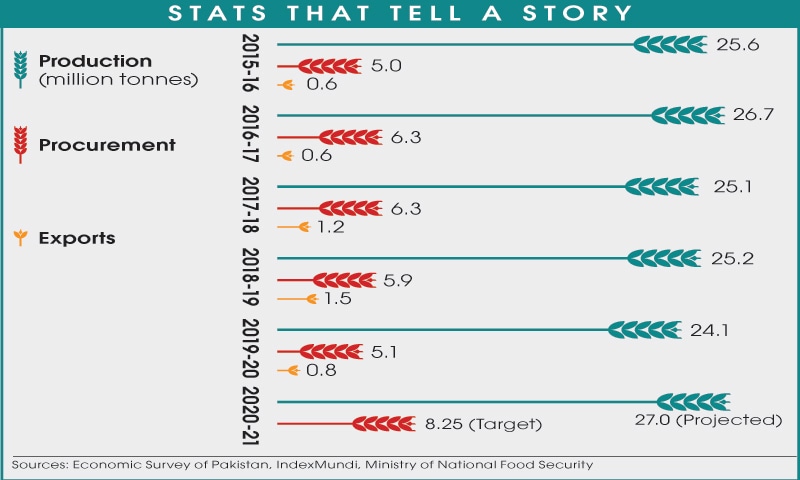

LAHORE: The government decision to increase the state’s already large footprints in the country’s heavily controlled wheat market through its enhanced purchases of 8.25 million tonnes of staple grain from growers this year will significantly increase its subsidy burden.

The targeted procurement is over 30 per cent of the total projected wheat harvest of 27m tonnes this year and more than 60pc of the crop surplus that will be brought to the market.

With the support price increased from Rs32,500/tonne to Rs34,125/tonne for the fresh harvest commencing in Sindh from this month and in Punjab from April, the decision means that the federal government and provinces will acquire new loans of Rs281.5 billion from the banks at commercial interest rates to finance their purchases.

This amount doesn’t include the significant expense that government will bear on gunny bags, grain storage, transportation, handling and distribution, etc. Nor does it include the cost of other incidentals — pilferage and losses from the public stocks, and recurring expenditure on maintaining a very large procurement infrastructure.

Experts say the current procurement system in Pakistan is expensive and most inefficient in the world

The new borrowings will add significantly to the aggregate debt stock of Rs775bn from federal and provincial commodity operations, which is often referred to as ‘wheat sector circular debt’, acquired in the past for public sector procurement. The debt stock is exclusive of millions of rupees government pays to service interest on this loan.

Thus, the cash-starved federal government and provinces, particularly Punjab, will accumulate considerably large fresh debt in addition to spending billions to achieve the twin objective of supporting farmers and subsidising retail flour prices, mainly for urban consumers, throughout the year. Punjab is estimated to have borne wheat subsidy expense of Rs291.2bn between 2012 and 2019 to support farmers and supply cheaper flour to consumers across the country, as well as in Afghanistan. In 2019, the federal government, and Punjab and Sindh together paid around Rs50bn in wheat subsidy.

The decision to procure more wheat is motivated by the recent ‘wheat flour crisis’ that had hit parts of the country, particularly Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, in mid January with the millers inflating their prices sharply as the product disappeared from the market despite enough public stocks to feed the country until fresh crop. Prime Minister Imran Khan drew a lot of flak for his government’s mismanagement of the wheat trade as images of people queuing up to buy flour outside stores and from government supply trucks on cold winter mornings hit front pages of newspapers.

Over time, government has become ‘principal buyer’ of domestic wheat, kicking the private sector out of the market. Additionally, it also sets the support price at which both the public and private sectors are supposed to buy the commodity from growers to give them guaranteed returns as an incentive to continue producing wheat to achieve food self-sufficiency and protect them from market failure. The scheme helps government provide flour at affordable retail prices to consumers.

Government operates in the market through provincial food departments and Pasco, a federal agency, to procure the commodity from farmers to build up stocks, which are later issued to flour mills at subsidized rates once flour millers have exhausted their own purchases. Normally, government procures 20-30pc of the crop or half of the quantity brought to the market.

Various studies have found existing procurement and distribution system as fiscally expensive and inefficient owing to massive costs borne by government to provide across-the-board subsidy. The policy serves politically connected large farmers, flour millers and traders well at the expense of significant cost to the budget, small-holders and consumers. Even the Competition Commission of Pakistan finds the scheme expensive and inefficient, and has termed its impact on farmers and consumers – for whom the system is designed – as questionable.

In the recent years, the higher than international wheat prices have encouraged farmers to grow substantially more wheat than was required for domestic consumption and led government to accumulate large stocks. Consequently, it had to spend millions of dollars on export subsidies to cover the gap between domestic and world prices as it offloaded some of its stocks accumulated in 2017 and before fresh purchases from the 2018 harvest. The subsidy offered was $120 per tonne on exports to Afghanistan and $160 per tonne on shipments to other destinations. The subsidy was repeatedly extended until July 1 last year even after Pakistani wheat became internationally competitive due to almost 50pc depreciation in the rupee value.

The current wheat support mechanism has also created excess capacity in the milling industry, especially along the border with Afghanistan where much of wheat flour is smuggled. A large number of these mills operate only when subsidized wheat is issued. Many mills are found involved in selling wheat issued to them from public stocks in the open market to profit from difference in the issue price and market rate. In the recent months, the Punjab government acted against 376 flour mills, imposed Rs90.6m in fines and suspended the license of 15 mills and wheat quota of 180 others, according to a report submitted to the high court.

Dr Naved Hamid, a prominent economist, says the current procurement system in Pakistan is very expensive and most inefficient in the world. “Whenever government gets involved in the market inefficiencies also creep in,” he asserted while talking to Dawn. “There are many other ways of achieving national food security objective; other countries have developed more effective and efficient mechanism for supporting their farmers.”

He is of the view that the government should maintain minimum strategic reserves, encouraging greater private sector participation in the post-harvest supply chain and physical handling of the commodity. “The issue of domestic price stability can be tackled by developing mercantile exchange where farmers, traders, millers and government could hedge against price risks through futures contracts, and removing restrictions on international trade to allow free wheat imports in years of shortages and exports in times of abundant domestic supplies to ensure trade policy certainty.

“In years of shortages, the government may subsidise imports if global prices are higher than domestic rates or the floor price set to protect farmers. In case world prices crash, the government can use tariffs to ensure imported wheat does not breach the floor price.

“It’s a complex subject but an efficient and effective alternative can be found to protect both farmers and consumers, and ensure national food security in spite of the vested interests who are benefitting from the present system.”

Faisal Rasheed, a public finance consultant, agrees with Dr Hamid. “The government needs to limit its intervention in the market to encourage private sector investment in procurement and storage of wheat and other crops,” he said.

He also opposed across-the-board subsidy on retail flour price, saying the government could cut its losses by building in all incidentals, and storage and other costs in the wheat issue price.

“That may somewhat spike retail flour prices and food inflation during couple of months before the arrival of the fresh crop, but the prices will come down when the harvest begins as is the case with other agricultural products. To protect the poor, the government can increase the amount it distributes among them under its cash transfers programme during those months,” Mr Rasheed says.

However, it is widely believed that it will never be an easy decision for any government to limit its role in the wheat market or stop giving untargeted subsidy – not for food security reasons but because of political considerations.

Published in Dawn, March 4th, 2020