Viruses: ancient, tiny, amazing

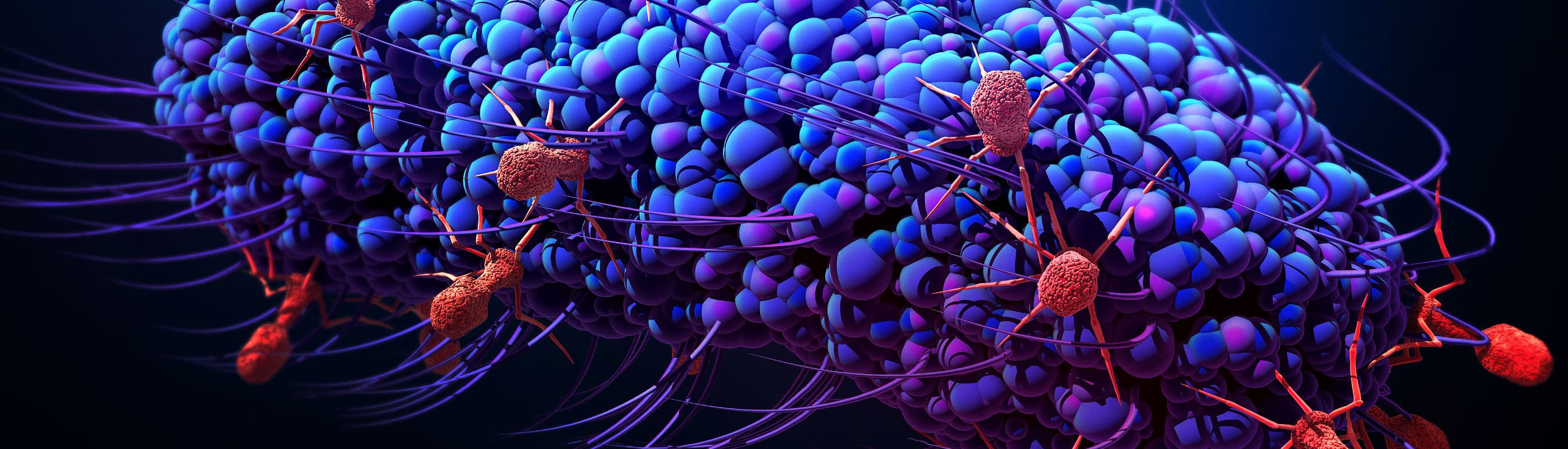

THEY are as old as life itself, but scientists cannot say for sure if they are alive. They are written into our DNA, shaping the human saga through mutation and resilience.We touch hundreds of millions of them every day.

As the novel coronavirus outbreak disrupts global markets and prompts unprecedented containment measures, it is worth asking a basic question: what, precisely, is a virus? What are they made of? Where did they come from? And, perhaps most importantly, why are they trying to kill us?

Unimaginable numbers

The story of viruses is perhaps best told through mind-bending figures.

According to Curtis Suttle, a virologist at the University of British Columbia, the physical properties of viruses make them hard for us to comprehend.

Their tiny size, for starters. If each virus in a human body grew to the size of a pinhead, the average adult would become 150 kilometres tall.

In a 2018 study, Suttle found more than 800 million viruses settle on each square metre of Earth every single day.

In a tablespoon of seawater there are typically more viruses than there are people in Europe.

“Most of us will swallow more than a billion viruses every time we go swimming,” said Suttle. “We are inundated by viruses.”

A 2011 paper published in Nature Microbiology estimated that there are 110 to the power 31 (more than one quintillion, or 1 followed by 31 zeros) viruses on Earth.

Lay them all end to end and they’d stretch 100 million light years, or 1,000 times the breadth of the Milky Way.

The virus as a concept

Viruses are best thought of as “molecular packages”, according to Teri Shors, professor of biology at the University of Wisconsin and author of several books on the subject.

“These packages have to be small enough to fit inside a cell to cause infection,” she said.

Essentially strings of genetic material contained by a few protein molecules, viruses occupy a strange middle ground between the living and the inert.

Since they don’t have cells and do not produce energy through respiration -- a key definition of living organisms -- many scientists don’t consider them to be alive.

Yet, as soon as they enter their host, viruses spring into activity in ways rarely seen in nature, hacking cells with new genetic instructions to replicate at dizzying speed.

Ed Rybicki, a virologist at the University of Cape Town, said viruses were “as much a concept as a thing”.

“I consider viruses to be alive, because when they are in a cell, they ARE the cell,” he said.

Shors said that viruses were “metabolically inactive”.

“Unless they can enter a warm body and get inside of a cell, viruses are inert,” she said.

But once it infects its host, “the entire cellular machinery is entirely devoted to making viral progeny”, said Suttle.

“This is the living virus.”

Published in Dawn, March 7th, 2020