Maddalena Ferrari lets herself cry when she takes off the surgical mask she wears even at home to protect her elderly parents from the coronavirus that surrounds her at work in one of Italy’s hardest-hit intensive care units.

In the privacy of her own bedroom, where no one can see, the nursing coordinator peels away the mask that both protects her and hides her, and weeps for all the patients lost that day at Bergamo’s Pope John XXIII Hospital.

“We’re losing an entire generation,” Ferrari said at the end of one of her shifts. “They still had so much to teach us."

The pressures on hospital ICUs in Italy and Spain may have eased in recent days as new virus cases decline. But the emotional and psychological toll the pandemic has taken on the doctors and nurses working there is only now beginning to emerge.

Already, two nurses in Italy have killed themselves, and psychologists have mobilised therapists and online platforms to provide free consultation for medical personnel. Individual hospitals hold small group therapy sessions to help staff cope with the trauma of seeing so much death among patients who are utterly alone.

Seven weeks into Italy’s outbreak, the world’s deadliest, the adrenaline rush that kept medical personnel going at the start has been replaced by crushing fatigue and fear of getting the virus, researchers say. With many doctors and nurses deprived of their normal family support because they are isolating themselves, the mental health of Italy and Spain’s overwhelmed medical personnel is now a focus of their already stressed health care systems.

“The adrenaline factor works for a month, maximum,” said Dr Alessandro Colombo, director of the health care training academy for the Lombardy region, who is researching the psychological toll of the outbreak on medical personnel. “We are entering the second month, so these people are physically and mentally tired.”

According to his preliminary research, the solitude of the patients has had a grievous impact on doctors and nurses. They are being asked to step in at the bedside of the dying in place of relatives and even priests. The sense of failure among hospital staff, he said, is overwhelming.

“Each time it’s a failure,” said Ferrari, the nursing coordinator at the Bergamo’ hospital. You do everything for the patient, and “at the end, if you’re a believer, there is someone above you who has decided another destiny for that person.”

Her colleague, Maria Berardelli, said medical personnel aren’t used to seeing patients die after two weeks on ventilators, and the emotional toll is devastating.

“This virus is strong. Strong, strong strong,” she said in a Skype interview with Ferrari, both of them in masks. “You cannot get used to it, because every patient has his own story.”

In Italy, the national association of nurses and psychologists asked the government for a coordinated, nationwide response for the mental health care needs of medical personnel, warning the “typical wave of stress disturbances is only going to grow over time.”

The situation is similar in Spain.

Dr Luis Díaz Izquierdo, from the emergency service ward in suburban Madrid’s Severo Ochoa Hospital, said the sense of helplessness is crushing for those who watch as patients deteriorate in a matter of hours.

“No matter what we did, they go, they pass away,” he said. “And that person knows that they are dying, because breathing becomes more difficult. And they look into your eyes, they get worse, until they finally surrender.”

Diego Alonso, a nurse at Hospital de la Princesa, said he has been using tranquilisers to cope, as have many of his colleagues. For Alonso, the fear is especially acute, given that his wife is due to give birth soon.

“The psychological stress from this time is going to be difficult to forget. It has just been too much,” he said.

Dr Julio Mayol, medical director at the San Carlos Clinic Hospital in Madrid, said staff will be suffering from “numerous scars” in both the short and long term.

In addition to the many dead and fears for their own safety, Mayol said staff had been traumatised by “the noise surrounding the pandemic,” with daily news of death tolls and suggestions that other countries are faring better than Spain.

“The fear, the envy and the fantasy in continuous communication, repeated 24 hours per day in media, has been an obsession that health workers couldn’t forget,” he said, adding that his hospital had mental health professionals working with patients and staff from the start, and that effort will continue.

At San Carlos, nearly 15 per cent of the 1,400-member staff have been infected, in line with medical workers nationwide.

In Italy, over 13,000 medical personnel have contracted the virus. More than 90 doctors and 20 nurses have died.

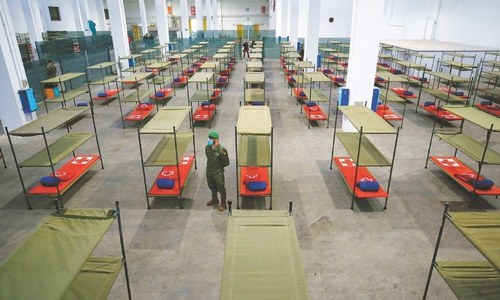

Perhaps no hospital has seen more than Pope John XXIII, where operating rooms were converted to ICUs to add 12 precious beds to meet the influx of patients.

Ferrari, the OR nursing coordinator, remembers March 18, the first day the ORs were open for ICU business. Eight intubated patients were wheeled in over the course of a shift, an overwhelming number for the staff.

Ferrari said she hadn’t had time for any of the group counselling sessions organised by the hospital but allows herself to weep once she gets home and says goodnight to her parents, whom she keeps at a distance behind her mask and latex gloves.

One day, the tears were triggered by TV footage of coffins being hauled from Bergamo by an army convoy. On another day, they flowed after she drove by a motorcade of trucks flying Russian flags that were heading to sanitise Bergamo’s virus-ravaged nursing homes.

Ferrari said she cries in the privacy of her bedroom.

“When I remove the mask, it’s like removing a protection (an armour) from my face, it’s like saying with this protection mask I don’t fear anything. It helps me appear strong,” she said. “And when I remove the surgical protection mask, then all my weakness comes out.”