THE RUPTURING OF THE CLOCKS

It took me weeks to finally mention the pandemic in my journal. Guiltily, out of an obligation to record the world. “By the way, Covid,” the entry on March 24 begins. “We’ve been under lockdown since yesterday.”

My therapist asked me if I was okay, whether I was panicking for the health of loved ones. My mom has sent over gloves and masks, I told her, plus a care package with tea and daal and lavender disinfectant, and I have thoroughly wiped down everything. “But are you worried?” she asked.

Maybe I was in some kind of floating shock, but I had no real feelings about the pandemic. I just had to make sure I got the cat’s food before 5pm, otherwise things were the same. People were putting themselves in voluntary lockdown, cancelling their social lives, halting work, not going out anymore. I really didn’t feel all that different. I’d been living like this for months.

There’s a children’s story by Leo Lionni about a little mouse called Frederick that I love. While other mice gather grain and pine nuts for the winter months, Frederick spends his time daydreaming, gathering colours and words. He’s berated for not helping out; what the mice really need are pine nuts, not poems. Frederick doesn’t care and does his thing. Winter comes and lasts longer than usual, and the mice run out of food. They couldn’t have planned for this. Cold and unhappy, they turn to Frederick now that there is nothing left to do, and the poet-mouse emerges with his poems, ready to share. The mice listen and sigh and stand corrected — poetry isn’t what they thought they needed — it doesn’t solve anyone’s hunger, but they can’t deny they all feel a little warmer.

Over time I started relating to the other mice more than Frederick. What is it that we think we need, and what is it that we turn to? Times of crisis offer a real chance to answer these questions. My crisis was the end of a relationship. A long winter in its own right. I hadn’t planned for this. Suddenly, everything thrown off track, up in the air. That was in November, and I found myself thinking about the mice. How did they survive without what they knew to be essential? And would they have listened to Frederick’s poems, if they hadn’t first run out of food?

What do I have to run out of, I thought, I was just bouncing, between mania and grief and disbelief. Maybe I had to run away from. And so I did something I never imagined I’d have the courage to, never imagined possible for myself in Karachi. Two months after the break-up, I got an apartment, informed my parents I was moving out, took my cat and left.

A leaving on my terms, as if it might make up for the one that wasn’t.

“Good!” a friend said. “When you lose a home that is a person, you need to find a new home.” And what better than this, a room of my own. Ridiculous now that I could stand in a balcony that was mine, watch light fall on a desk where I would not be interrupted, leave books around and trust they wouldn’t be moved. It was too unreal, someone else’s life. What was I to do with it? I was crying and sleeping my days away, depressed and inconsolable. Friends came by, assuring me I’d get over this whole thing soon enough, reminding me I was finally unaccounted for and unaccountable, answerable to no one, I wasn’t trapped, I was free.

Put all your energy into the space, they encouraged me, think about how you can nurture it. Yellow curtains, I answered mechanically, and a low wooden table. It’s been three months and I’ve gotten neither.

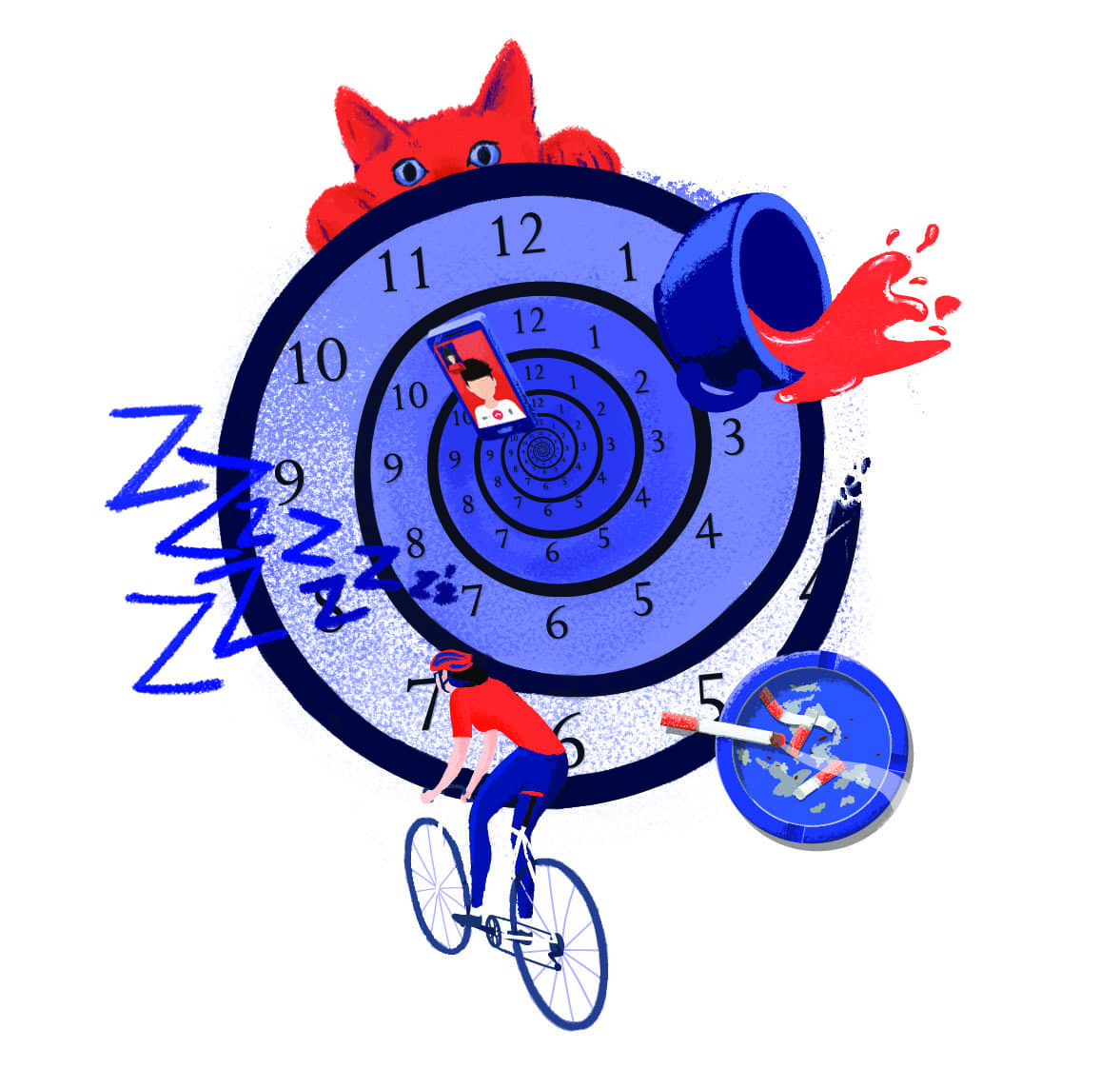

Something rewires deep when clocks rupture, when their unthinkingness is seen. One doesn’t need a collective upheaval to know that; daily we survive and swallow small deaths, shift with them.

That was before Covid. Since January, I have been on what I jokingly call a grief-lockdown. I stayed indoors for days, until I ran out of cigarettes or cat food. Aside from the weekly trek for therapy, I hardly left the neighbourhood; simply had no desire to. The city felt garish and open, too much stimuli. I was too exposed, and terrified I’d run into my ex. Staying in felt safest. Sleeping, even more. Ottessa Moshfegh’s novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation had convinced me that sentencing myself to a retreat might not be such a terrible idea. A year of this, and I’d emerge fully healed and recovered, ready to face life.

Because really, I wasn’t facing much. Privilege and dissociation — a special combination that allowed me to cancel everything. I withdrew from professional commitments, missed deadlines, stopped responding to editors. There was enough to tend to in the apartment to ensure I couldn’t completely check out, and a cat to take care of, but most of my awake hours I did nothing. Sat and watched the light, restacked my books, let my cat lick me. Friends came plenty, cooked with me, ran errands, just hung about, cheering and consoling me. I was grateful for the constant buzz of people, the comfort it brought, but when they left the grief doubled. Even when they were around, my mind was elsewhere, listening lackadaisically to them talking about work, their creative lives, the latest in feminist circles. I was stuck, uninterested, always on some verge. All I wanted to do was unload, talk about what happened, and why, and why. Unaccountable and unaccounted for, I really didn’t know how to answer to myself.

The smallest things sent me reeling. Getting a new book. Recognising a warbler from its sound. Chai overspilling on the stove. When rejections came from writing residencies, I felt nothing. I was smoking myself to a dreg, measuring days from cigarette to cigarette, dreading sleep, whether it would come, and in what shape. Sometimes it came after sunset, and I woke up at 2am. Other days I’d be up past 24 hours, mind running, running, maniacally watching the changing colours in the strip of sky visible from my balcony. What I preferred were whole-day sleeping marathons, how they let me erase time. But most of all I craved consistency, and felt worse each time I failed to find it.

“Spend days like you have no clocks,” my friend Aesha suggested. “Wake up when you want, sleep when you want. What does it matter?”

Smart advice; it helped me befriend the night and fall in love with the morning. All expectations off the table, because really I wasn’t meeting them anyway, now I often began my day in the quietest hours of morning without judging myself. The world had its clocks, I had mine. I woke at 2am, put on that lonely cup of chai, forced myself to move. While the city slept and recovered, I was engaging in a different recovery: gathering the things I loved back into my life. Distracted and haphazard, as much as I could manage each day. Journaling, language practice, reading. Sometimes I just listened to music and smoked. And if I did nothing and cried, that was fine too; the goal was to treat it as a regular day, keep moving, stay awake. There was sunrise to look forward to, some release there, my strip of sky breathing colour just in case I was worried I’d exhausted everything.

One morning was so spectacularly wretched, I decided to go outside to see the sunrise. I hadn’t stepped out since January on just a whim. The dhabay wala was also surprised to see me. “You’re going to have tea here?” Two months I had been living in this lane, getting chai and qahva delivered through Abdul Bhai, I’d never actually sat there and had tea. I can’t sleep, I told him, and placed the chair where I could watch the street and horizon both; 7am and just me and my grief and a bewildered chaiwala. The sky opened. My heart did not, so I focused on my senses, bringing my attention to the things around me. Slowly, slowly. The meat shop shutters clanging open. Fresh smells from a truck heaving in vegetables. The creak of a pipe being dislodged from a Suzuki for the morning water refill.

It was absurd. That the world could carry on with its clocks while mine had ruptured.

In my early days of abandoning clocks, I met Hijrat. It was another sunrise morning at the dhaba. “God knows why my parents thought of this stupid name,” he said. “You’ve definitely met other Sadias in your life, right? Everyone meets someone who shares their name. Only I’ve never met another Hijrat.” In fact, he was the only Hijrat I have ever met, and the only person in the world who, three minutes into our conversation, tried to convince me to quit writing. I came back, not dispirited at all, but laughing, and thinking fondly of the moment of our encounter. I was pulling a chair to place it at the spot from where I liked to watch the waking street, when Hijrat appeared with a friend and ordered chai as well. In a moment of unintended coordination, we placed our chairs in alignment, a neat-semi circle. One of those city moments I live for.

I responded to other wretched nights by taking my cycle out at sunrise. I have never known myself to be a morning person so there was a strange curiosity to these ventures, like watching myself to see what I might do next. Inwardly I sent a prayer to my ex and thanked his grief — it was changing my relationship with mornings, and with cycling, which was starting to feel almost spiritual, the highlight of my day. I don’t know how to explain it, wary of giving definite language to an experience I still feel at the helm of. Something about the steady hum you reach when your body syncs with wheels. The sky lifting above the ocean. One day, near Seaview, light rain on my back, except it wasn’t rain, but sea spray. Sea spray! It tickles you like that only because of the speed of the bicycle. I started crying. All my life in Karachi, and I’d never felt the sea on my skin like this.

Cycling in the evenings, I feel less unsafe because there are so many cops around. No long empty stretches to pass through worrying about stalkers. Feeling grateful for surveillance. Dystopia.

Wandering around the neighbourhood one day — I still didn’t go beyond these cosy streets — I found a thrift shop. Bought mugs and ashtrays and teacups, and frames to bring back and place in the apartment I was slowly furnishing with things that were mine. The yellow curtains were still pending, but I’d have to go and get them made, and maybe didn’t want to anymore. They would block my full clear view of the play unfolding on the opposite building, the one I could tune into anytime. The pigeons hopping mad all day, chasing each other in turns, the mynahs’ ballet on the electric wires.

I was slowly getting to know the human characters, too. Those were two different women in that kitchen window, one who leaned out to dump garbage and yell instructions at someone named Ali, who smiled at me if our eyes met in the mornings. The other, younger, liked to hang by the window when talking on the phone. A boy appeared intermittently in the middle window to spit out paan. On the left, lived a middle-aged guy whose voice had me convinced he was a radio host. He seemed to live alone, but had friends over in the evenings; I heard laughter from the room.

Between these people and Hijrat and Abdul Bhai and Muneer at the superstore who apologised whenever they ran out of pink cake, I was getting to know a whole new range of new people in my life. And their playlists. Someone blasted Teri Deewani and O Re Piya often in the afternoons, at night a Tupac-lover emerged. And there was definitely one person who shared my obsession for the Aashiqui 2 album; when they took over the street DJ-ing, I turned off my own speakers, just listening with them. I wondered what these people thought of my playlists, my bhajans and Bieber. It was good to think of myself through strangers’ eyes, people I’d never have to know well. It was good to fill life with strangers, with distance.

Strange, distance, how it’s expanded, collapsed. The few friends who came over don’t anymore, but more are available any minute, on Houseparty, Zoom, Instagram, Twitter. I always thought of dystopia as something that would stand out, but perhaps the most dystopian thing about dystopia is how easily and unthinkingly we get absorbed into the new normal. Normal for all interactions to have moved online, as if the world were always primed for it. I haven’t seen Hijrat or Abdul Bhai in weeks. Last month, I was courting a mad sleeping cycle. Now I am virtually accompanying Vishal in New York down his street when he goes to buy cigarettes, I’m in his pocket and can see the American sky.

When I leave the house, I diligently put on a mask and wear gloves, out on the street I gauge people’s expressions through their eyes. A police van pulls in at 5pm to force shutters down, I don’t bat an eyelid. Cycling in the evenings, I feel less unsafe because there are so many cops around. No long empty stretches to pass through worrying about stalkers. Feeling grateful for surveillance. Dystopia.

At home, I am logged on to video calls all the time. Vishal and I hang out for hours, playing songs in turn, a listening party across oceans as we each do our own thing. It is normal for time zones and borders to not matter in the same way anymore, and somehow reveal they never did.

“For the first time,” Aesha says, “It feels like external reality is matching internal reality.”

On the day the lockdown was announced, she came at 8pm and woke me up. I’m locking down with you, she said, matter-of-factly. And I remember thinking, not about the pandemic, or about the coming deaths that had necessitated cities to shut down, but most selfishly: how grateful I was for love, of any kind, to show up, to choose to shut itself down with you.

Now she wouldn’t have to go home, I wouldn’t have to wait another day to see her. The comfort helps, the physical presence, the intimacy on hand. To take love for granted like this. We’re finding new rhythms to our friendship. Putting on chai for the other without asking, knowing when it’s time for silence. We read, cook, listen to Shabnam Virmani and Tinariwen a lot. Sign up for courses, all these sudden free classes. On the one hand the world shutting down, on the other, new imaginations of generosity. Libraries making books available online, JSTOR releasing its archives.

Maybe all this is too much and my body doesn’t have the room to deal with pandemic-level philosophical self-investigations. In any case, how do body and mind absorb a change so ongoing? My #1 hope is for deceleration, though part of me is curiously welcoming the unprecedented surrealities.

Grander acts of kindness too; through the internet, people offering to run errands for elders, giving free services in exchange for donations for Corona relief efforts. Then smaller joys, Instagram and YouTube abundant with live streams: Ali Sethi everyday, Shilpa Rao on Rekhta, Chance when he feels like. Since the lockdown I have joined two writing circles and one book club, reading War and Peace with #TolstoyTogether.

Days move easy and open in our cocoon of comfort and privilege. We’re reminded of Corona every now and then, but it seems to have little bearing on our bubbled lives. Sometimes we watch our neighbours and the pigeons; wonder how they’re dealing. The woman at the window always got her vegetables delivered, but now everyone’s doing the same. The man appears more and more, looking bored, tired. We make up stories and wonder how their lives might have changed. His friends have stopped coming, Aesha reasons, no more poker and carom nights. That’s why he’s restless and coming to the window so often.

I find myself restlessly coming back to this bit from Jenny Offill’s novel Weather. “My #1 fear is the acceleration of days. No such thing supposedly, but I swear I can feel it.”

Underlying panic at the store the other day. Not more crowded than before Covid, but the shelves are messier, and everyone is hurried and frenzied. Main uncle at the counter is urging the packaging guy to move faster, handling two bills simultaneously though really there’s no reason to — there’s no line. When I ask him if they have brown eggs as I usually do, he’s exasperated. “I don’t know bhai, just whatever is there is there!” While I’m still going around picking things he yells, “I’LL BE WITH YOU IN A MINUTE!” and I hear it in all caps, and I haven’t even said anything.

Things to note; they’re out of Twix, Dayfresh, Gold Leaf whites. I ask a helper if he can bring sugar from upstairs. “I just can’t, right now,” he pants, then collapses, hands on knees. “I just can’t, I am done, can everyone WAIT!”

Take a moment and breathe, I tell him. Do you want a glass of water?

Or maybe this is the dystopian part: I wake up, log on. Check the numbers. Next day, they’ve doubled. It doesn’t shake me. I obsessively keep reporting statistics and updates to Aesha. Really, I’m hoping to make myself feel something. London maybe in lockdown till the end of May, I tell her, New Zealand has frozen rent. But the facts accumulate like dead information, lacking the power to affect me, to spur me to care. Friends are making masks, volunteering, collecting rations to help out. What am I doing? Learning about attachment styles, reading poetry, watching endless videos on how to make souffle pancakes.

Maybe all this is too much and my body doesn’t have the room to deal with pandemic-level philosophical self-investigations. In any case, how do body and mind absorb a change so ongoing? My #1 hope is for deceleration, though part of me is curiously welcoming the unprecedented surrealities.

In Russia, I learn on Twitter, lions are released on the streets to force people to stay in. In Chicago, an aquarium let its penguins roam free since it was closed for visitors, and more in Florida and Vancouver followed suit. All these penguins suddenly loitering. The world is a novel writing itself. In India, Modi is apparently asking people to bang utensils in their balconies at the same time everyday to create a frequency that will fight the Corona.

So much upturning, I think maybe my emotions will magically stop following their tired tracks too. Anything is possible. But then the Russia lions news turns out to be fake, and I realise, no, everything is not actually possible. People will believe anything. The novel I will have to write myself.

There is what you should do about a situation, and how you actually feel. I should join my friends in organising drives. I should get myself together and write. I should just get over my ex and move on with my life.

It’s not that hard. People deal with worse all the time. People, in the background, are.

Then there are hours when dystopia looks kinder than I’d imagined. Evenings out cycling, the city is a version of the one I know, but brighter, less hostile. The whole stretch along Seaview, people walking, jogging, cycling, skipping. Like some beach town in another country, my friend notes. And if I crop out the policemen, the landscape doesn’t look so gendered either. There are aunties laughing as they jog together, women exercising and doing yoga, little girls leaping with dogs. You’d almost believe the chaar deevari was an outdated concept here.

The sea, it somehow looks cleaner. And I swear the birds have gotten louder.

One morning a policeman stops me cycling at night, and I momentarily panic, sure I’ve done something wrong. But he yells, “Aap ne helmet aur mask donon pehnay hain! [You are wearing both a helmet and a mask!] GOOD JOB!” and thumbs-ups away.

Terrifying also, this ability to romanticise the city when deaths are piling everywhere.

I cannot get these lines by Li-Young Lee out of my head: “There are days we live / as if death were nowhere / in the background”. In the poem, living without death in the background has to do with dwelling “from joy / to joy to joy, from wing to wing”. I kept these lines close as intention and aspiration; the spirit of flight, to live a life measured by the abandon of joy. But these days when I think about them, I just feel guilty.

Is it fair to tend to what I owe to myself, before I look at what I owe the world?

Not fair, you could say, to make this distinction.

In astrology circles, my sister tells me, this year is huge. Saturn’s wrecking the heavens, creating a lot of tumult in the skies. The prediction being that a major event is unfolding, and the human species is not going to come out of this experience the same. Apparently, this big shift will have something to do with our comprehension of time.

Already everyone has been talking about clocks. No Zoom catch-up call goes without addressing three things: how time is spent (either relentless productivity or passionate laziness); what we think is going to happen to the world once we’re out of lockdown (anarchy, upheaval, back to the same); and how slowly everyone is losing their mind. The reasons vary: Covid is getting too much, they’re worried and troubled, this is worse than the Spanish plague, staying in is taking a toll. I can’t relate, still can’t register involvement or culpability. Even the guilt on some level feels manufactured. Nor can I compare my self-imposed lockdown to the pandemic shutdown. When I decided to stay in, I had the comfort of knowing that the world was out there, I would come out whenever I was ready.

But the world we will collectively walk back into, now, is both uncertain and unknown. And it cannot be the same as before, whether you believe in astrology or not. Something rewires deep when clocks rupture, when their unthinkingness is seen. One doesn’t need a collective upheaval to know that; daily we survive and swallow small deaths, shift with them. Changing habits and places, friends and lovers. We know it intuitively.

But maybe there is a difference between choosing to go inward to introspect, and being thrust there. What happens when the thrusting is not a private, interior storm, but a shared, global spectacle? A collective sentence on the world’s body and psyche? How do we make sense of something like that?

Leo Tolstoy on clocks: “As in the mechanism of a clock, so also in the mechanism of military action, the movement once given is just as irrepressible until the final results, and just as indifferently motionless are the parts of the mechanism not yet involved in the action even in a moment before movement is transmitted to them. Wheels whizz on their axles, cogs catch, fast-spinning pulleys whirr, yet the neighbouring wheel is as calm and immobile; but a moment comes — the lever catches, and, obedient to its movement, the wheel creaks, turning, and merges into one movement with the whole, the result and purpose of which are incomprehensible to it.”

This time is a suspension, one friend says, and lockdown sure, but not a trap at all. Whole weeks of pause, suspension, rest. RESET! What will we re-imagine and re-make? That’s what he’s thinking about.

What I’m thinking about: What is it that we think we need, and what is it that we turn to?

In that journal entry where I first mentioned Covid, I only wrote a paragraph about it, then returned to regular programming: thoughts on heartbreak, on the light in the apartment that day, salty and cool, how maybe it is steadily healing me, how a mynah’s feet look like tiny tree barks, drained of brown. How I’m thinking about the architect who designed this space, bless them, well-positioned openings so air flowing all day and you can hear the city as long as you’re present and paying attention, and you never really have to believe you’re shut inside.

How do we emerge from any rupture? The word emerge — bring forth, bring to light — comes from the latin emergere, e meaning ‘out, forth’ and mergere meaning ‘to dip’. Like rising from a liquid by mastering buoyancy. Frederick emerged with poems because he dipped inward, sank into light and colours and poetry. What are we sinking into, when we are allowing ourselves to at all.

Header image: The Persistence of Memory (1931), Salvador Dali

The writer is based in Karachi and writes fiction and non-fiction, dealing with themes of gender, public spaces, visual culture, cities and poetry. She is currently writing her first book, a memoir on the life and work of the late Kashmiri-American poet, Agha Shahid Ali. She is also one of the founders of the feminist collective Girls at Dhabas

Published in Dawn, EOS, April 12th, 2020