THE discussion about the future power generation and its affordability remains subdued as the authorities concerned firm up the Indicative Generation Capacity Expansion Plan 2047.

Despite initial costs and long gestation periods, hydropower plants have almost no fuel cost and have operational lives of over a century. New hydropower plants generate electricity at Rs6-10 per unit compared to thermal power plants’ Rs15-25 per unit. All other power-generating technologies have up to 30 years of project life and need up to four times expensive plant replacements in foreign exchange.

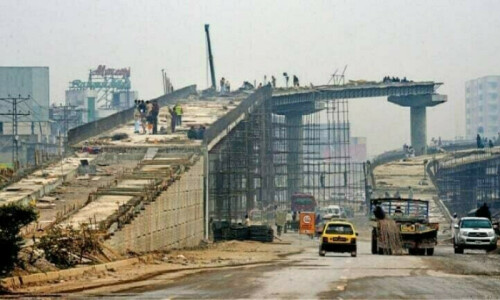

Hydropower has the lowest life-cycle cost of any generation technology. Hydropower is a potential life-saver for Pakistan. Yet its development has been hampered for decades. Hence, only 15 per cent of Pakistan’s over 60,000MW hydropower potential has been developed in 70 years. This hostility, despite sporadic government interest, continues.

On the other hand, powerful lobbies backed the construction of thousands of megawatts of public-sector power plants that burn imported fuels. They are developed with massive policy breaches and out-of-turn privileges. The fact remains that the country now faces a power surplus after highly expensive surplus RLNG generation replaced costly furnace oil generation.

Under power policies, power plants can be visualised as leased vehicles — the monthly lease amount must be paid whether the vehicle is used or not. But it is rare to pay the fuel cost when the vehicle is not being used. That is unique with the design of RLNG plants of thousands of megawatts.

Hydel projects with approved sites and available finances are being pushed back in favour of wind and solar plants that have no sponsors, planning or grid evacuation studies

Wind and solar are intermittent technologies reliant solely on weather. They can at best supplement but not replace hydropower which, amongst others, can provide a range of valuable services, including frequency control, grid balancing, water storage, quick start and peaking services not inherent in wind and solar generation.

Hydropower projects that have approved sites, available finances, approved tariffs and strong sponsors are being pushed back, thus effectively killing them in favour of renewables (mainly wind, solar and small hydro) that still have no sponsors, sites, financing, planning or grid evacuation studies.

It makes no sense to abandon large privately funded hydropower projects developed without any government investment and having a fixed approved tariff with the cost of delays and overruns borne by the private sponsor.

Pakistan has a longstanding romance with imports. Governments love to construct power plants using imported fuel, which is the most expensive option in terms of operating costs, not plant capital cost. In the long run, they will produce the most expensive power owing to the erratic international hydrocarbon market and the persisting devaluation of the rupee.

Pakistan planned five imported coal projects i.e. Hub, Sahiwal, Rahim Yar Khan, Port Qasim and Jamshoro (6,600MW in total) and four imported LNG projects namely Bhiki, Haveli Bahadur Shah, Balloki and Trimmu (4,900MW in total), giving a total capacity of 11,500MW constructed in record time. It was all based on imported fuel. Once these plants were in place, well-entrenched babus in the power ministry announced a moratorium, saying the country now had surplus power.

Such a situation has occurred many times in Pakistan’s history: first they create a shortage of power and then construct several thousand megawatts of thermal power on the pretext that the emergency situation demands rapid construction of thermal plants as their establishment is quick. Once this is done, a surplus is declared and the development of all hydropower projects is halted until the next power shortage occurs and then the cycle is repeated.

It has to be kept in mind that many of hydropower resources are located in Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan. Unfortunately, international financiers have stopped lending for projects in Azad Jammu and Kashmir owing to its disputed territorial status and pressure from India. The 350MW Athmuqam project on the Neelum River (Azad Jammu and Kashmir) and 4,500MW Diamer-Bhasha on the Indus (Gilgit-Baltistan) are its examples.

Several other projects, including the 300MW Ashkot hydropower project on the Neelum River, may meet the same fate if the government delays their construction in the name of surplus thermal capacity, which is based on imported coal and RNLNG. In one scenario, the Diamer-Bhasha hydropower project is optimised for generation in 2047.

The rupee has devalued 7.45pc per annum in the past 20 years. On this basis, the fuel cost of $3.64bn today would be about $7bn per annum in 10 years, $10bn in 15 years and $14bn in 20 years. In line with this, the LNG power generation cost, which is at present Rs8.57 per unit (kWh), would rise to Rs34 per unit (fuel only) in 20 years. The cost of coal alone (variable), which is presently Rs6.96 per unit, would rise to Rs27 per unit (fuel only) in 20 years.

But the generation cost of hydropower (variable), which today is Rs0.62, would rise to Rs1.01 in 20 years as most of the variable cost is in local currency.

We need to recognise the realities of our situation and the inevitable devaluation at close to historic rates to plan ahead so that our generation inputs are least reliant on imported fuel. This will save us from the explosion of tariffs owing to the rupee devaluation. The devaluation had about Rs186bn additional cost in the power tariff this year alone.

Published in Dawn, The Business and Finance Weekly, May 4th , 2020