My cellphone rings and the voice on the other side sounds familiar. The lady is none other than Haseena Moin, who needs no introduction. “You have been one of the three or four people who have nudged me time and again to pick up my pen and go beyond the first chapter of my memoirs…I want to tell you that I’m on the fourth chapter and am writing with renewed zest.”

The eminent playwright for the mini screen and currently the chairperson of the Karachi Arts Council’s literary committee has, thanks to the Covid-19 scare, been confined to her home in Karachi’s North Nazimabad.

She reveals that she has just finished writing about her childhood days. In the third chapter, the 1941-Kanpur born Haseena narrates how she migrated to Pakistan. She recalls that she and her family were safely transported in the special train that took them and families of other government servants from the trouble-torn UP (United Province, later renamed Uttar Pradesh) to Bombay, from where a coastal liner, whose name she can’t recall, brought them to Karachi. That was sometime in September 1947.

By the way, she never liked the name Haseena. It was imposed on her by an aunt who was very close to her parents. “I haven’t still forgiven her,” the lady admits. “For many years I wished to change it but just couldn’t.”

Haseena follows odd hours. She works till the early hours of the morning. These days in Ramazan, she writes till the time she says her Fajr prayers, and then hits her bed. Even when she’s not fasting, she gets up in the afternoon and takes her first meal of the day, which she insists on calling her breakfast, not her lunch. No wonder, the night bird’s favourite fragrance is that of the raat ki rani.

Eminent playwright Haseena Moin is presently in the process of penning her memoirs, taking advantage of being locked down in her home. She recounts events in her past now taking shape as chapters in her book

“By the time your piece will appear in print, I would have written how I had done my first play. Just to curb your curiosity, let me tell you I used to contribute to the handwritten magazine, which was displayed prominently on the premises of Government College for Women on what used to be Frere Road in Karachi. One day Mrs Shanul Haq Haqee, who was the Head of the Urdu Department, insisted that I should write a play to be staged in the college. I did.

“The 25-minute play, which was titled Patriyan [Railway Tracks], clicked beyond my expectations.The senior programme producer of Radio Pakistan Karachi, Agha Nasir, and well-known playwright Zakir Hussain, who were seated in the front row, asked me to write for what was then one of the two most prestigious broadcasting stations — the other was Lahore. Thus I started writing plays for the one-hour slot on Sunday called Studio Number Nau, which enjoyed a very high listenership.

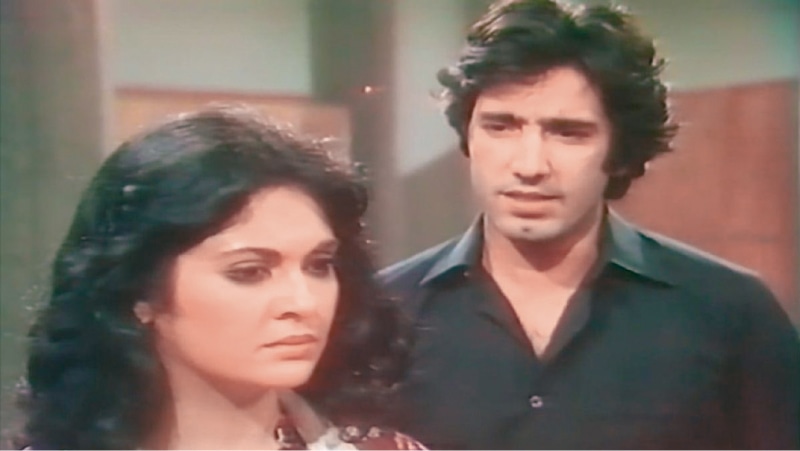

“In the following chapter, I shall write about my forays into the new audio-visual medium,” she continues, referring to television. “I shall start with the long play called Happy Eid Mubarak, starring Shakeel and Neelofer Aleem. The same pair appeared in my first serial Shahzori, which was adapted from a novel by Azeem Beg Chughtai. You know he was the elder brother of the famous writer of fiction…”

“Yes, I do,” I interject, but before I can mention the name of Ismat Chughtai, Haseena does.

She has a long list of people, she says, she owes a lot to. The first Managing Director of PTV Aslam Azhar, Agha Nasir and poet Iftikhar Arif get a special mention. She enjoyed writing for a number of TV producers. The two names that Haseena wants me to mention in particular are Syed Mohsin Ali and Shireen Khan, both highly accomplished TV producers. Sadly, both died when they were quite young. Way back in 1974, the talented twosome worked separately on her script of Uncle Urfi. If one of them was recording an episode, the other would be planning the production of the next episode. Thus Haseena wrote for both of them and to say that the serial was watched by tens of thousands is to downplay its cultural cache.

As for actors and actresses who played different characters in her long plays and serials, she says, the list is too long to be mentioned.

I point out to Haseena that the heroines of her serials such as the ones portrayed by Roohi Bano in Kiran Kahani, Shahnaz Shaikh in Ankahi, Marina Khan in Tanhaiyaan or Dhoop Kinaray and Sahira Kazmi in Parchhaiyaan, seem to have all been cast in the same mould. They are unmistakably similar: strong-willed, if not headstrong. I wonder whether they were alter-egos of herself.

“Quite obviously, they are birds of the same feather. I modeled them on my own personality. I was full of life, I was frivolous, impish and quick on the uptake in my teens and my twenties, even in my thirties,” comes the spontaneous answer, leaving no room for any more speculation on the subject.

I remind Haseena of the serial that she did for the Indian TV producer Chanda Narang and she suddenly sounds highly enthusiastic. Kashmakash, a 13- episode serial, was the first, and perhaps the only one, penned by a Pakistani to appear on Doordarshan, the Indian government-owned TV channel. Chanda, a close friend of fashion designer Shamaeel, came all the way from Delhi to get the script done by her. Incidentally, its title song was composed by Arshad Mahmud and recorded in the voice of Tina Sani.

Narang, who became a close friend of Haseena’s, hosted her in Delhi and later took her to different places such as Chandigarrh, Ranipur and Mehrabpur, when the Pakistani writer had no visa for all these places. But she won many new friends and perhaps influenced no less a number.

How does Haseena interweave plot and characters is a subject one should leave for her to throw light on in one of the later chapters.

I then ask Haseena why she never wrote for the stage, except once in her college days. “Well, I did quite recently. I adapted my two serials Shahzori and Ankahi for stage. Had Covid-19 not played spoilsport, at least one of the plays would have been staged in April,” she responds. Considering that Anwar Maqsood’s Aangan Terrha had been a major hit, Haseena’s plays would probably do quite well too, whenever they finally see light of day. Haseena gets highly charged, if one may use the expression, when I ask her how did Raj Kapoor get in touch with her and signed her to write the dialogue of Henna, the story of which was penned by the eminent writer Khawaja Ahmad Abbas. The details of hospitality shown to her and her younger sister, who had flown with her to Mumbai, and how she accepted Kapoor’s offer will be a part of one chapter, while the subsequent chapter will give details of her next two trips.

Haseena recalls that during their conversations, the Peshawar-born Raj Kapoor had time and again quoted from the Holy Quran and translated those verses into what was a mixture of English and Urdu.

Haseena mentions that Raj Kapoor wanted a Pakistani girl to play the title role. She suggested the name of Zeba Bakhtiar and asked him to watch the Pakistani TV serial Taansen, which featured her.

“Please do write that I was shocked by the death of Rishi Kapoor, whom I met for the first time when he was in his twenties.” Haseena has herself fought a ferocious battle against cancer and was lucky to emerge successfully. She may well narrate the grim details in her memoirs.

But one chapter will be missed in her memoirs and, no prizes for guessing, it will be about matrimony. Haseena has remained single all her life. I discreetly mention it to her and it seems she was waiting for the inevitable question. “Had I gotten married, I wouldn’t have been able to write all these serials. One of my elder sisters wrote two novels but after her marriage she couldn’t scribble a single word,” is her answer.

In retrospect, it seems quite a plausible one.

Published in Dawn, ICON, May 17th, 2020

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.