As a nation state, the security of a country is not guaranteed by its militarised, well-guarded borders alone. It depends equally on the collective strength of the state’s socio-economic and political institutions. The crisis created by the coronavirus pandemic has accentuated this reality for world nations and exposed the weak institutions of underdeveloped countries like Pakistan. As countries are forced into easing lockdown restrictions to limit economic fallouts, the transition also presents an opportunity for governments to reflect on their policies, administration and politics. “In a crisis, be aware of the danger, but recognise the opportunity,” John F. Kennedy famously said. As the number of infected cases peaks and the impending economic crunch looms larger, what policy measures can Pakistan take in order to prepare itself for the future?

Environs for epidemics

Based on Pakistan’s geographical location, the issue of epidemic preparedness is a pressing concern for the country.

The map (top right) shows the geographical distribution of countries grouped in five quintiles, with varied degrees of epidemic preparedness, 1 being the most prepared and 5 being the least prepared. Considering the spectrum, Europe, China, North America, Brazil and Russia are among those countries that fall in quintile 1 and 2 — that is, they have relatively high epidemic preparedness. However, India falls in quintile 4 whereas Pakistan falls in quintile 5, being one of the least epidemic prepared countries.

Most pandemics, for instance the Spanish flu in 1918, SARS between 2002-2004, the Avian influenza 1997 and Covid-19, have occurred due to zoonotic spark, that is pathogens transmitted from animals into humans. Research suggests that this spark can result from either domesticated animals or wildlife. In the case of domesticated animals, it is prevalent in areas with extensive livestock production systems such as in China, India, Japan, United States and Western Europe. This has a direct correlation with the socio-economic arrangements of a state.

Owing to our most recent experience with the pandemic, it can be seen that the risk of a zoonotic spark does not need to be indigenous. Once it surfaces in a country, its spread does not respect state boundaries. Therefore, a country’s geographical location and its proximity to any country prone to zoonotic spark is an important consideration. Since Pakistan shares its borders with China and India, both countries with a strong potential for zoonotic spark, it is persistently vulnerable to an outbreak. Therefore, more state preparedness is needed to respond in the event of a pandemic.

Now is the time to consider a more holistic strategy to respond to and manage disasters, keeping in mind the interdependence of all economic sectors

A grave concern, particularly for developing countries with insufficient resources and infrastructure, is that the likelihood of pandemics has increased over the past century due to rampant globalisation, interconnectedness, urbanisation and the excessive exploitation of natural resources. Covid-19 has hit the country and it may well subside, but the constant threat of recurring pandemics due to geographical placement will remain an imminent danger.

The economic threat

Pandemics are multifaceted crises. Therefore, tackling them requires state capacity on multiple fronts.

In the event any health emergency, the healthcare system is set in motion for immediate response. To strengthen states’ public health response, International Health Regulations (IHR) were adopted by the World Health Assembly in 1969. These regulations were later revised in 2005 and enforced in 2007 on all World Health Organisation (WHO) partner states. The binding guidelines provide a set of core competencies in order to build strong indigenous health departments. These competencies include: legislation, coordination, surveillance, response, preparedness, risk communication, human resource development and laboratory capacity. The regulations further laid down an inter-sectoral approach, connecting health capacity with agriculture, transport and other industries.

The international health regulations place the health department at the heart of a well functioning economy. Its connection with the agricultural sector is a holistic approach towards human health, animal health and food security.

For instance, post implementing a nationwide lockdown, the entire food supply chain in Pakistan was disrupted. There was an immediate shortage of labour to harvest summer fruits and wheat crops on the one hand, and a lack of transportation to the market on the other. This also made it difficult for farmers who managed to harvest their crops to sell their produce. All this poses threats of food security. Therefore, multi-sectoral linkages underscore the interconnectedness of each sector and their eventual dependence on a strong health system. This interconnectedness also indicates that a health crisis brings with it other associated crises such as social, economic, political and international.

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and the World Bank’s Global Monitoring Report, Covid-19 has affected more than four out of five, or almost 81 percent, of the global workforce, in countries under full or partial lockdown.

As per estimates by Deutsche Bank, the US economy is expected to shrink by 40 percent in the second quarter of 2020 following lockdowns. China’s economy shrank by 6.8 percent in the first quarter this year. The US unemployment rate, which stood at 3.5 percent in February 2020, has now jumped to 14.7 percent, the highest since the Great Depression. With people losing their jobs in cities in India, the overall unemployment rate of the country has hit 26 percent in the third week of April. In South Africa, where the unemployment rate, even before the pandemic, was almost 30 percent, Covid-19 has put almost 1.5 million jobs in peril.

With mounting economic pressure, economies around the world are forced to consider easing lockdowns. France and Spain, two of the countries hardest hit by Covid-19, have also started lifting restrictions. However, by our experience with Covid-19 until now, we have already seen how far the aftershocks of a health crisis can be felt.

According to the World Bank’s South Asia Economic Focus report, owing to Covid-19, South Asia will experience the worst economic performance in the past 40 years. In the worst-case scenario, the entire region might experience negative growth this year. However, Pakistan’s real GDP growth

is likely to shrink by 1.3 percent to 2.2 percent, with a possibility of falling into economic depression. That is to say, for the first time since 1950, Pakistan’s GDP growth could be negative.

An overwhelmed healthcare system

As per the World Bank’s data of 2016, Pakistan spends around 2.8 percent of its GDP on health. There is no denying that Pakistan’s healthcare system is extremely weak because of consistent governmental negligence. In a span of almost a month, the number of Covid-19 cases has drastically shot up. Pakistan’s state authorities rightfully fear that, soon, the healthcare system will be overwhelmed if reported cases continue to rise at the current pace.

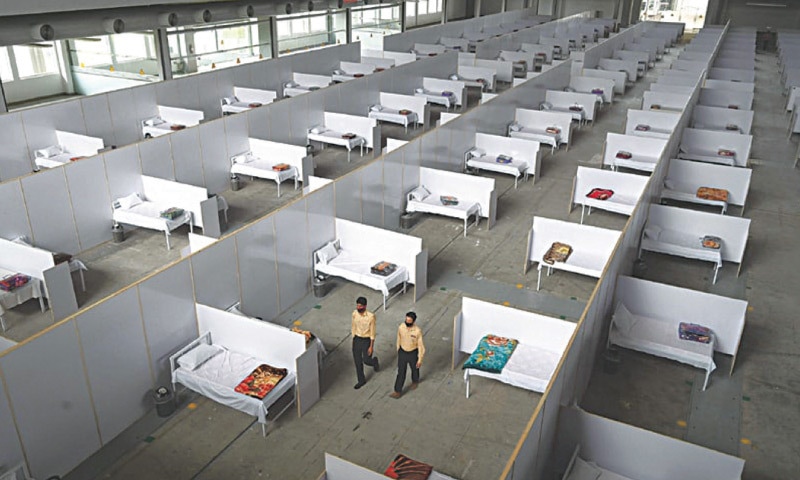

WHO projects that, by mid-July, Pakistan’s cases can surge up to 200,000. Considering the existing facilities and bed utilisation (solely based on the government website for Covid-19), Pakistan’s needs will outrun its facilities. Meanwhile, doctors and the government have been at odds over the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) kits and, so far, nearly 100 doctors across the country have tested positive, with at least three reported deaths. We have previously seen Italy’s situation aggravated when their medical staff started getting infected.

Now with the easing of lockdown restrictions, an unprecedented increase in daily cases can certainly be expected. This will only place added pressure on the already dilapidated healthcare system across the country.

Pakistan’s Emergency Response Apparatus

Effective crisis management entails an understanding of the crisis itself. However, the official document which underpins Pakistan’s emergency response does not present a sound distinction between crisis, emergency and a disaster.

The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) acts according to the National Disaster Response Plan (NDRP), when the country is declared to be in an emergency. According to the NDRP, the NDMA is responsible for performing pre-disaster, during disaster and post-disaster activities. The NDRP outlines that pre-disaster activities begin “when an incident has grown into a crisis or emergency, with the possibility of becoming a full-blown disaster.”

According to the NDRP documents, emergencies (also used interchangeably with ‘disaster’) are classified into four categories, depending upon the capacity of districts, provinces and the federal government to handle the disaster. In case the disaster is beyond the capacity of the government, the Prime Minister of Pakistan can make an appeal to the international community for support. [Covid-19] is being regarded as a “global crisis”, however, Pakistan’s NDRP has no mention of the term whatsoever. The plan’s central focus is to manage and respond to national emergencies; the emphasis on disaster prevention is therefore compromised.

In this regard, Pakistan can learn from its all-weather friend China. Post-SARS, the Chinese government reformed its emergency management system and, in 2007, passed the Emergency Response Law of the People’s Republic of China. The law was aimed at preventing and reducing the occurrence of emergencies, along with measures to control, mitigate and eliminate harms for public and national security. Following this change in the emergency management system, the Chinese government also simultaneously introduced changes in the public health emergency management system, for a more holistic handling of national emergencies.

Countries such as China, the US, the UK and South Korea have dedicated centres for disease control and prevention to protect their citizens from local and foreign health and safety threats. Similarly, Singapore has its National Centre for Infectious Diseases. These institutes help create knowledge for disease control and complement their country’s crisis management strategies. Whereas NDMA does recognise pandemics as a potential disaster, its organogram does not indicate any research facility that comprises virologists or epidemiologists who could generate knowledge to proactively safeguard people against potential health hazards.

The way forward

Governments around the globe are now adopting varying containment and mitigation strategies to protect lives and minimise the fears of unemployment in their respective countries, and have pledged hundreds of billions of dollars to help ease the pain on their populations, and to support businesses and their healthcare systems. But for the world to be better prepared, the global discourse and policymaking process for future challenges must be through the lens of a societal view, where, post-pandemic, the constituent elements of an economy are holistically viewed.

In Pakistan, the federal and provincial governments need to revisit international health regulations, to put in place the required competencies as advised by WHO to ensure a robust healthcare system — one which produces highly sought-after healthcare professionals.

This would entail better governance, organisational restructuring and rational budgetary allocations to the provincial health departments. Higher education institutions of the country need to revisit their institutional focus and their academic, industrial and sectoral relevance. These institutions of higher learning can transform themselves as centres of not just knowledge generation, but also of planning and offering support to the government in terms of policymaking. Provincial governments need to have more secure food supply chains in place. There is a greater need of government-supported storage facilities at the district level, particularly for perishable crops, to avoid food losses in emergency situations. Similarly, arrangements need to be made for better price controls of agricultural products.

This is certainly the hardest of times for the world at large. But it is also a ripe time for us to put our own house in order.

Qazi Muhammad Zulqurnain Ul Haq is founding executive director of Youth Center for Research. Nadeem Hussain is co-author of The Economy of Modern Sindh (Oxford University Press, 2019)

Published in Dawn, EOS, May 17th, 2020

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.