CHINA VS INDIA: GEOPOLITICS OF A CLASH

PRESENT-DAY

As in most of the world, the coronavirus was the biggest story in India until recently. That changed when news of a violent clash between the Indian Army and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops on the night of June 15 broke. Two weeks on, the story continues to dominate the Indian airwaves. It makes sense. China and India have a rocky past and this latest clash left 20 Indian troops, including the commanding officer of 16 Bihar, the unit involved in the clash, dead. Over 100 other soldiers from the unit received non-life-threatening injuries. Three days after the clash, PLA returned 10 captured Indian Army personnel, including one lieutenant colonel and three majors.

Before the June 15 clash in Galwan in Ladakh, after several rounds of meetings between local commanders and at least two meetings at the level of major generals which didn’t resolve the issues, India and China held lieutenant-general-level talks on June 6. Reports suggested that the Chinese side, led by Major General Liu Lin, commander of South Xinjiang Military Region, refused to discuss Chinese positions in Galwan.

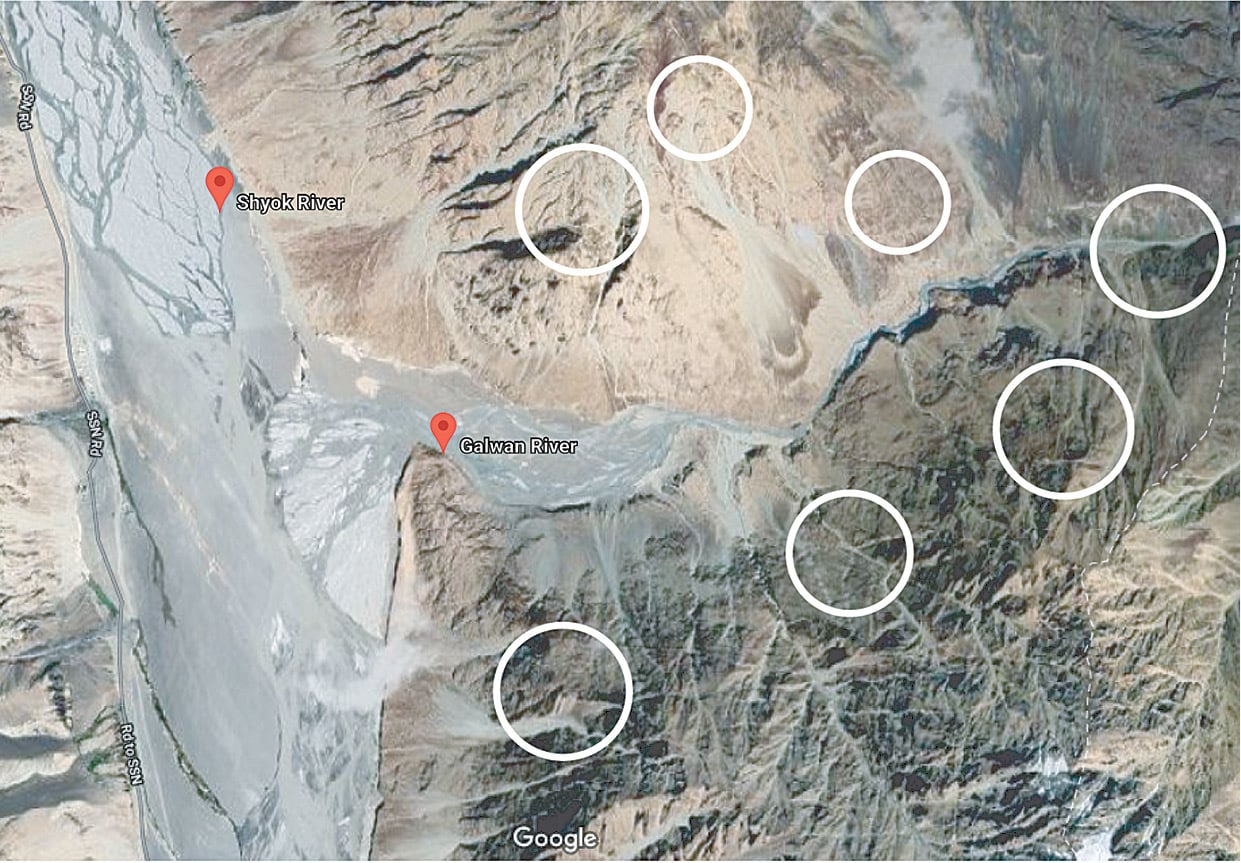

Keeping Galwan off the table was not without operational sense. PLA troops have positioned themselves on high ground in the sector at the confluence of Galwan and Shyok Rivers. These positions give them the advantage of observing and, if required, interdicting India’s crucial line of communication, the Durbak-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DSDBO) Road. Galwan, thus, acquires a more than tactical advantage, as we shall shortly discuss.

In the theatre of operations, the other places where PLA troops have come up to their claim line include Hot Springs, south of Galwan, Pangong Tso, a high-altitude lake further south and Demchok, the southernmost point of forward PLA deployments. Each of these points gives PLA a tactical advantage and combined turn that into a theatre advantage (see accompanying map). Incidentally, Pangong Tso is the lake where a Bollywood film, 3 Idiots, filmed a song. The Line of Actual Control (LAC) slices through the lake with about one-third on the western Indian side and the rest on the Chinese side.

Therefore, any analysis of the situation and forward deployments have to be seen at the tactical, theatre and politico-strategic levels.

WHAT IS BEING SAID

Expectedly, the Indian media, including many defence analysts, blame China for ingressing into Indian territory, west of the LAC. This claim is false on two counts: one, as per the UN Resolutions on Jammu and Kashmir, India is in illegal occupation of territory, including Ladakh, where we are witnessing the current stand-off between India and China; two, as described by Indians themselves, the LAC is not demarcated and both sides have their claim lines — Indian patrols show their presence east of the LAC, while PLA patrols push west of it.

Ironically, China’s claim that its troops are present on Chinese territory is in line with the argument mounted by the Indian side, including by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who said in a televised statement that Chinese troops had not intruded across the country’s borders. Modi’s statement contradicted the position taken by his foreign minister.

While there are two sectors where India and China meet, the other being in the east where the boundaries of Nepal end, this article will primarily focus on the western sector, which is eastern Ladakh and currently the theatre of tensions.

PLA troops have positioned themselves on high ground in the sector at the confluence of Galwan and Shyok Rivers. These positions give them the advantage of observing and, if required, interdicting India’s crucial line of communication, the Durbak-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DSDBO) Road. Galwan, thus, acquires a more than tactical advantage.

Many Indian and foreign analysts have tried to figure out why the border has suddenly flared up. This question is important for many reasons:

• The June 15 clash in Galwan is the second, though more violent, such incident in more than 45 years. Before the Galwan incident, Indian and PLA troops clashed on May 5/6 and then 16/17 in the Pangong area. At least 72 troops on the Indian side sustained injuries and the commanding officer of the unit, 11 Mahar, sustained life-threatening injuries.

• On September 7, 1993, the two sides had entered into an agreement that binds them to resolve the boundary question through peaceful means, though it also states that “The two sides agree that references to the line of actual control in this Agreement do not prejudice their respective positions on the boundary question.”

• The 1993 agreement was bolstered by more specific provisions in a 1996 arrangement.

• The latest arrangement is the 2013 Border Defence Cooperation Agreement (BDCA). On October 23, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh met with Chinese Premier Li Keqiang to sign the BDCA in the wake of a stand-off in Depsang (Daulat Beg Oldie) area (northwest of Galwan).

• India and China trade, as of 2019, stood at 85 billion dollars, with both sides committed to enhancing the trade volume and China allowing India to reduce the latter’s 50 billion dollar trade deficit.

• Finally, overall, relations between the two have been improving since former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s path-breaking visit to China in 1988.

WHY NOW…

So, what happened?

Various reasons are being put forward for China’s assertive behaviour. The most favourite with analysts, in India and elsewhere, is the argument that China has responded to India’s improvement of its lines of communication infrastructure along the LAC. Most such analyses suggest that this is what China has been doing for long on its side and, now that India has taken a leaf out of China’s playbook, the latter has reacted.

Standalone, this argument is a lazy way out of a more complex situation. Its relevance, however, increases if you plug it into other developments that combine enhanced capabilities with intentions. Consider:

• India reopened the Daulat Beg Oldie (DBO) air base in 2008. It had abandoned it during the 1962 war with China, when troops stationed there just left helter-skelter, though the PLA never got to DBO and never occupied it. By 2013, the Indian Air Force had built the DBO advanced landing ground to the point that its transport aircraft C-130 and C-130J-30 could land there. While China was aware of this development, it didn’t protest.

• Ditto for the DSDBO all-weather road, that was commissioned to be built in 2000. However, in 2011 it was found that there was a problem with the alignment of the DSDBO Road and work had to be initiated to realign it. Most of it was completed in 2019. India has also constructed a Bailey bridge — the Col Chewang Rinchen Setu — on Shyok River, which was inaugurated in October 2019. Both the road and bridge cut down the time for reinforcements or forward deployments of troops and equipment from two days to just six hours. India is also building feeder communication lines to the east from the main DSDBO Road to supply its deployments.

It should be obvious that with other developments at the politico-strategic level, these tactical and theatre developments assume military-operational significance.

The other reason trotted out by various analysts, notably the Indian-American scholar Ashley Tellis, are about a China under pressure internally and from the world on the mishandling of the Covid-19 crisis, an economic downturn, troubles in Hong Kong etc. In other words, Xi Jinping is facing the heat at home and wants to be assertive abroad.

Yet another argument pins these developments on India’s strategic partnership with the US, Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategy and India’s inclusion in the Quad (short for Quadrilateral Security Dialogue), which includes the US, India, Japan and, now, Australia. As a February 2019 report, carried online by research organisation RAND, notes, “For now, the US is probably content with simply using the Quad as a way to signal unified resolve against China’s growing assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific, without directly antagonising Beijing. That may change in the future if US–China relations deteriorate further, or Beijing’s behaviour towards regional neighbours becomes even more aggressive.”

Interestingly, all these arguments, while being pieces of the larger puzzle, miss out the elephant in the Buddhist tale about the blind men and the elephant. Each piece (the part of the elephant) is considered to be the whole. It is not. Let’s get to the elephant then.

PIECING TOGETHER THE PUZZLE

Military and strategic preparedness is a function not just of intentions, but also of current and evolving capabilities. Equally, when State X sees that State Y is not only developing its capabilities through alliances and bandwagoning, but is also giving expression to changing intentions, X would opt for its own action that best suits its security and other interests.

History, both general and military, shows that the best time to negotiate or change the ground situation is from a position of strength. Weakness begets a bad deal. It is in this context that all the pieces come together. DBO, DSDBO, the road’s off-ramps, bridges, infrastructure, Indo-US partnership etc become meaningful not singly, but in tandem, and with the expression of new intentions.

While the Indian media is flagging and flogging specific provisions from the 1993, 1996 and 2013 bilateral arrangements and accusing China of violating those agreements, they are forgetting two key developments since the current Indian government took power.

This is where we come to the decision by New Delhi to illegally bifurcate and annex the occupied territory of Jammu and Kashmir, including Ladakh. Not only that, but the Indian government brought both Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh under direct rule from Delhi, by downgrading the status of Jammu and Kashmir — of which Ladakh was a part — into two separate Union Territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh.

India’s argument is that it was an internal matter violates bilateral understandings with Pakistan (Simla/Lahore), China (1993, 1996, 2013) and UN Resolutions that have determined the State of Jammu and Kashmir as disputed territory. Additionally, New Delhi issued official maps that show the liberated areas of Azad Kashmir, Gilgit-Baltistan and Aksai Chin as part of India. The latter claim was not missed by Beijing.

For Beijing, this is intention and capabilities (alliances) trying to bridge the differential. From a military-operational perspective, laying claim to Aksai Chin translates into a strategic intent to sever Tibet’s link with Xinjiang. As a former Indian Army GOC-in-C Northern Command, Lt-Gen HS Panag wrote: “Much as I would like to speculate about China’s broader political aims, the direct political aim is simple — to maintain the ‘status quo’ along the LAC on its own terms, which is to forestall any threat, howsoever remote, to Aksai Chin and NH 219.” China’s response is perfectly in line with sensible operational strategy because today’s ‘remote’, if left unchecked, can be tomorrow’s ‘imminent’.

China’s pre-emption of the forward-leaning posture of the Indian Army (and state) has, therefore, to be seen and appreciated in terms both of capabilities and intentions. Luckily for China, India showed its hand (intentions and false bravado) before it had acquired matching capabilities. For China to have waited until the capabilities were aligned with intentions would have been operational and strategic folly.

The recent stand-off and analysis must, therefore, move from the tactical (Galwan or Pangong Tso encounters) to the theatre (multiple pressures on nodal points in eastern Ladakh) to the politico-strategic. But this is where one must revisit history and the 1962 War.

THE SINO-INDIAN WAR OF 1962

The year 2020 is not 1962. Or, as Mark Twain said, or is supposed to have said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” A lot has changed and, yet, we have striking similarities.

One of the most authoritative accounts of the Sino-Indian War of 1962 is Neville Maxwell’s India’s China War. Recently, Bertil Lintner, a Swedish journalist, has tried to critique Maxwell’s book by writing his, reversing the title to China’s India War: Collision Course on the Roof of the World (published 2018). This is not the space to examine Lintner’s arguments in detail, though I will refer to them in passing. But let’s get to Maxwell’s arguments.

Maxwell’s book traces the root of the problem to its history when India was ruled by the British and both London and its Delhi representatives had two concerns: how to thwart the likely advance of Russia and what kind of forward policy would be required to ensure that the British and the Russian empires do not come abutting the same frontier. From the Durand Line separating today’s Pakistan from Afghanistan to the Macartney-MacDonald Line in Ladakh to the McMahon Line in today’s eastern front between India and China, the leitmotif of British policy was to create buffers.

The details are too many and often complex and this is not the space to go into them. But what is interesting, as Maxwell shows, is that the post-colonial states inherited these, often, undemarcated borders and swore by them — just like their colonial masters. As Gunnar Myrdal said: “The first and almost instinctive reaction of every new government was to hold fast to the territory bequeathed to it. What the colonial power had ruled, the new state must rule.”

As Maxwell says: “The decision [by Nehru] not to submit the McMahon line to renegotiation had closed off the possibility of formal agreement between India and China on that alignment.

“But at least the McMahon line was a known alignment marked clearly — though not precisely — on maps, and known to both the Indians and the Chinese. In the western sector, to which Nehru now applied the same approach, the situation was fundamentally different. There, there had never been any proposed alignment as clear as the McMahon line, nor indeed had the area been sufficiently surveyed to make it possible to draw such a line.”

Military and strategic preparedness is a function not just of intentions, but also of current and evolving capabilities. Equally, when State X sees that State Y is not only developing its capabilities through alliances and bandwagoning, but is also giving expression to changing intentions, X would opt for its own action that best suits its security and other interests. History, both general and military, shows that the best time to negotiate or change the ground situation is from a position of strength.

In fact, Nehru’s policy of giving the Chinese fait accompli comes out strongly in G S Bajpai’s correspondence with India’s Ministry of External Affairs. Bajpai had retired and was the Governor of Bombay (Mumbai). As the former senior-most officer in the MEA, he wrote to his ministry and urged “that India should take the initiative in raising the question of the McMahon Line with the Chinese Government.” Nehru discussed this with his ambassador to China, K M Panikkar, who then wrote to Bajpai, giving the reasons for why it was not prudent to do so. Bajpai wasn’t convinced and wrote back with his arguments but it came to nothing. As Maxwell notes, “Bajpai’s last comments were a footnote to a closed issue.”

Maxwell, who had access to the Henderson-Brooks-Bhagat report, has detailed Nehru’s “forward policy” and its consequences. Brooks was an Australian who chose to serve in the Indian Army and retired as a lieutenant-general. PS Bhagat, then a brigadier (retired as a lieutenant-general), was the other officer charged with inquiring into the conduct of 1962 war. Maxwell thus got a near-ringside view of the findings into the 1962 debacle. Successive Indian governments have refused to declassify and release that inquiry report.

Lintner’s main objection to Maxwell’s argument is that China was prepared with its military eco-system to invade India and, therefore, Maxwell’s argument that the war was the result of Nehru’s forward policy does not hold. His related argument is that China had studiously gathered and collated human intelligence within the Tibetan-speaking populations along the LAC, and the PLA knew where to strike. That must have taken time.

Neither argument really contradicts Maxwell’s book. China couldn’t sit back and let India grab the initiative after Nehru spurned Mao’s proposed line of demarcation. Of course, they were building up and consolidating, both in their forward deployments, as well as in the rear. They would have been militarily incompetent not to do so.

This brings us to what happened when the war began!

NEHRU’S DESPERATION

On November 19, 1962, barely a few hours after having written a letter to President John F Kennedy to request United States military assistance, a desperate Indian prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, sent another despatch.

Kennedy received the letter a little past 10 pm. The Chinese army advance, Nehru wrote, was now threatening the entire Brahmaputra Valley and “unless something is done immediately to stem the tide, the whole of Assam, Tripura, Manipur and Nagaland would also pass into Chinese hands.”

India had already received sizeable military assistance from a joint airlift by the US and Royal Air Force, a fact that had displeased Pakistan, because Washington hadn’t taken Karachi (then Pakistan’s capital) into confidence.

The question for Kennedy was not whether to help India, but how. Nehru’s desperate new appeal for help was expansive in scope and threatened to drag the US into a war with China, just nine years after the Korean War.

Bruce Riedel, a former CIA officer, in his 2015 book, JFK’s Forgotten Crisis: Tibet, the CIA, and Sino-Indian War, writes: “In this second letter Nehru was, in fact, asking Kennedy for some 350 combat aircraft and crews: twelve squadrons of fighter aircraft with twenty-four jets in each and two bomber squadrons. At least 10,000 personnel would be needed to staff and operate the jets, provide radar support, and conduct logistical support for the operation.”

Kennedy immediately sought advice from, among others, Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara. Rusk advised sending C-130 transport planes immediately to help the Indian Army with their supply lines, but McNamara argued that the US needed to get a good sense of the ground situation before the president could take a decision.

Ambassador Averell Harriman was sent at the head of a fact-finding delegation to determine what the Indians needed. By the time Harriman’s team reached Delhi on 22 November, Beijing (Peking) had announced a unilateral ceasefire on November 21, to come into effect in 24 hours. Also, beginning December 1, PLA troops were to “withdraw to positions twenty kilometres behind the line of actual control (LAC) which existed between China and India on November 7, 1959.”

Riedel argues that sending Harriman, “an icon of American diplomacy”, meant that Kennedy was serious in developing a military nexus with India. He cites not just the importance Kennedy put on such a partnership against China in choosing Harriman to lead the mission, but argues that the air defence exercise of 1963, planned during Harriman’s visit, was more than just symbolic. The exercise to defend India’s airspace was conducted just weeks before Kennedy’s assassination.

The Kennedy administration also drew up a five-year 500 million dollar military aid programme, which was to be finalised at a National Security Council meeting in Washington on November 26, 1963. Four days before that, Kennedy was assassinated. Further details of how that plan went nowhere are irrelevant to this space.

THEN AND TODAY

While history is not repeating itself, it is rhyming, nonetheless. The 1962 war was laid at the door of Mao for being in trouble at home because of the failure of the Great Leap Forward policy. Today, analysts are trotting out the argument that Xi Jinping, the Chinese president, is making assertive moves on the chessboard (South China Sea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, eastern Ladakh) because of his poor handling of the Covid-19 crisis. This is delusional at best and self-serving at worst.

China is a rising challenger. Like all powerful states, Beijing has interests in its near-abroad and farther. But its Monroe Doctrine is not just about military power, albeit that is rising and important. It wants connectivity, becoming the hub from where many spokes emerge. India should know this, given its own behaviour towards smaller neighbours. It can either be a partner with China or a rival that seeks to develop its potential for rivalry by joining the US bloc. That is a decision for India to make.

China’s moves are a signal to India. How do you want to play the game? It’s psychological, the escalation dynamic. China seeks to retain escalation dominance at all the three levels: tactical (Galwan/Pangong Tso), at the theatre level (all tactical nodal points) and at the politico-strategic level (where states collide or cooperate).

As I have written elsewhere, “if India refuses to climb up the escalation ladder, it is forced to treat the issue as a border-management rather than a military-operational problem. There, the PLA… has a clear advantage: it holds ground and is not prepared to cede it. India either has to accept China’s superior strategic orientation or try to change the reality on the ground.

“Chess has a term for it: zugzwang. India is obliged to make a move in its turn, but making that move could become a serious disadvantage for it.”

Header: A June 16 satellite image taken over Galwan Valley shows Chinese camps build-up in the region | Planet Labs via AP

The writer is a journalist interested in defence and security issues. He tweets @ejazhaider

WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR PAKISTAN?

The current stand-off is taking place in eastern Ladakh, a territory under India’s illegal occupation and part of the larger dispute related to Jammu and Kashmir. Some analysts have suggested that China, by inserting itself into the question of Ladakh’s status, has turned the issue of Jammu and Kashmir into a three-actor problem.

This is true but not for the reason of Ladakh’s status. Leh used to be part of Tibet at one time. According to eminent Kashmiri journalist Iftikhar Gilani, China’s official position during talks so far has been to ask India to give up its claim on Aksai Chin and draw the LAC clearly into a boundary. Interestingly, as per Chinese maps, the LAC crosses near Leh.

The three-actor play is more in terms of two triangles: China, India and Pakistan on the one hand, and China, India and the US on the other. Pakistan also overlaps these triangles, at which point it becomes more like a four-actor play.

Many analysts in recent days have said that if China pressures India any further, India will be pushed into Washington’s camp. This assessment seems to forget that the US and India are already in a strategic partnership and, while there may be some kinks in the relationship because of President Donald Trump’s way of handling not just adversaries but also allies, the Blob — the term that Obama speechwriter Ben Rhodes coined to characterise the US foreign policy community — remains structurally invested in relations with India. Another president would be able to straighten those kinks somewhat easily.

Add to that the US’ competition with China and India’s rivalry with the latter, and India and the US become natural allies. However, India would need a major pressure push from China to abandon trade and investment relations with Beijing.

Once again, history is a good guide. As Nehru’s letter to Kennedy shows, Nehru had to swallow his pride and seek US help during the 1962 war. Today’s India, going back nearly two decades, has been steadily coming closer to the US. It is no more a non-aligned state.

Again, history is a good guide with reference to Pakistan. At the time Kennedy decided to get the British onboard and send military supplies to India without informing President Ayub Khan, Pakistan was termed the most allied ally of the US. As Riedel recounts in his book (and others like Dennis Kux et al have also noted), the US had promised Pakistan that it won’t militarily help India against China. Not only did Washington renege on that promise, it warned Pakistan against opening another front in an attempt to take back Kashmir and stretch the Indian Army.

Today, while Pakistan and the US remain locked in a transactional relationship in Afghanistan, the sheen is long gone. Pakistan, always close to China, is even closer today with Beijing’s CPEC investments. It would be naive to think that Islamabad and Beijing are not exchanging notes on what’s unfolding in eastern Ladakh. Yet, it would be equally simplistic to think that there’s about to be a pincer movement by the two against India. China has its own reasons for doing what it has embarked upon, and that policy does not include any free lunches or simplistic scenarios.

Could present Sino-Indian tensions become militarily bigger and involve the US and its allies on the side of India? Riedel, writing about the 1962 war, thinks the US would have come out on the side of India if Mao hadn’t declared a unilateral ceasefire. As an interesting footnote, during those days, India allowed the US to fly U-2 spy planes from its soil over Tibet and, more importantly, Xinjiang, especially China’s Lop Nur nuclear test site. That’s how the US got intel on China’s nuclear test preparations.

What could be the US’ possible response in the multi-actor play? In a recent article, As China and India Clash, JFK’s “Forgotten Crisis” is Back, Riedel rounded off by writing this:

“There are many differences in the balance of power between 1962 and today, both regionally and in terms of global power balances… The past haunts the present…Neither Beijing, New Delhi, nor Islamabad had nuclear weapons in 1962. The risks of escalating the confrontation are immensely more dangerous today. All the players know that they have to avoid the worst. It’s too bad that the United States has a president who is certainly no JFK.”

Published in Dawn, EOS, June 28th, 2020