In usual circumstances, we might not like the eyes of strangers gazing into our homes and workspaces but that is what we inadvertently do ourselves to ohters as we look at our screens during conference video calls.

As if voyeuristically, we are peering into someone’s personal space, catching a glimpse of their familiar surroundings. Visible in the background of each online speaker may be a wallpaper, a chandelier, paintings or wall decorations or just the mundane clutter of everyday life in a workspace. These details instantly attract our attention, drawing us in with curiosity about the personal taste, interests and even status of who we can see on our screens.

In the past, it was artists who were hired to project or hide a certain image of their sitters. The personal space of the artists’ subjects would often reveal important clues about them. In hindsight, when we look at such paintings today, the details contained in them are also a historical document that provides insight into the aesthetics that dominated the era in which they were painted.

For instance, an important Indian miniature painting by Ghulam Ali Khan from the late Mughal period, showing Bahadur Shah Zafar’s son and grandson at the Mughal Summer Palace in Mehrauli, conveys more than just the technical finesse of the painter. It captures the minutiae of a private space, and is replete with objects that reflect the fashion and taste of the time.

How much do our surroundings in portraits or video call backgrounds reveal about our interior lives?

It depicts Mirza Fakhruddin and his son Mirza Abu Bakht seated in their salon, enjoying an evening with their musicians, or perhaps poets. One can see huqqas, paandaan, spittoons and a bowl of garlands on the floor — all these objects reveal to us the nature of the gathering and the activity taking place. However, the mantelpiece and walls of the salon are full of objects that show the dominance of English taste. A gilded mirror with a coat of arms of the English East India Company, a painting with a golden frame, two miniature portraits of British men in oval frames, candle holders, glass domes with vases and flowers are seen in the same space. These were objects more likely to be found on the mantelpiece in a home in Victorian England. Did Mirza Fakhruddin want to project himself as an Anglophile? Perhaps Ghulam Ali Khan’s meticulous depiction of objects documents something more than a vignette of the interior life at the Summer Palace.

The relationship between portrait sitters and objects in personal space as markers of status also acquired new meaning in Europe at this time. In the 1850s, Japan opened itself to commercial trade with the United States, after over 200 years of maintaining borders that were closed for trade or travel. This initiated a craze for Japanese goods in Europe and a French term ‘Japonisme’ was coined to describe this frenzy for owning Japanese objects and prints.

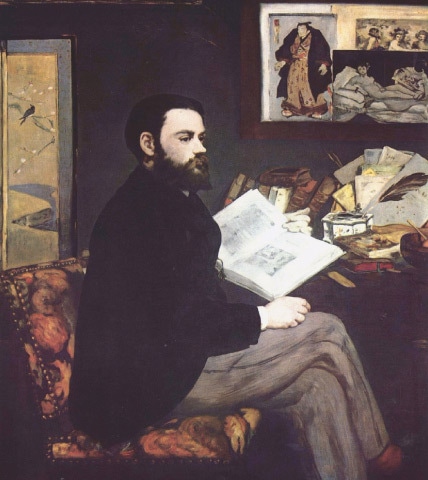

As a result, many important European painters began making paintings that show their sitters posing with imported Japanese objects. Perhaps in order to appear both erudite and an ardent admirer of all that was ‘exotic’ and ‘foreign’ at the time, French painter Edouard Manet has shown journalist, novelist and playright Émile Zola reading in his study with a Japanese print stuck to the wall of his modest workspace. The edge of a Japanese screen is also visible in the left-hand corner.

Impressionist painters such as Manet and Berthe Morisot used the Japanese fan as a recurring motif in all of their paintings of prone female figures daintily fanning themselves in intimate spaces. Sometimes the walls, too, were covered with Japanese fans, so that it became difficult to identify the space, location or even identity of the sitter.

Vincent van Gogh’s portrait of a paint shop owner he visited, titled ‘Père Tanguy’, shows him in a frontal pose with a background completely covered with bright Japanese prints like a wallpaper. Perhaps it is to turn away the prying eyes that peer into and judge our imperfect, flawed personal spaces, that Zoom also offers the option of virtual backgrounds. Like Tanguy, we too can now imagine ourselves in unreal spaces, devoid of personal objects.

Published in Dawn, EOS, June 28th, 2020

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.