"For ordinary people like us, life is made up of numbers of small details that stay with us for no particular reason and turn into treasured memories.” Rao Pingru’s Our Story: A Memoir of Love and Life in China is a biographical account in graphic form, that tells the story of a Chinese couple born in the early 20th century and their love and hardships as they traversed the staggering political and social transformation of China. Their story only comes to an end in 2008 when Rao’s wife Meitang passed away.

In order to save their cherished memories after her death, Pingru, at the age of 87, started to turn them into watercolour paintings. This beautifully bound volume brings those simple yet striking paintings together with moving and poignant prose.

Translated into English by Nicky Harman and narrated in simple chronological order, the memoir starts off by portraying what their early childhood was like. Even though Pingru and Meitang both knew of each other when they were kids, it was only after their marriage had been arranged by their parents that they got to properly know each other.

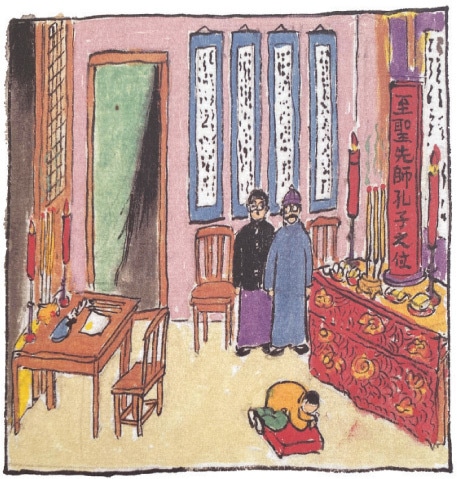

As well as memorable incidents from their lives, the book also explains a lot about the importance of various social norms in China and how they were taught to children from an early age. The initiation ceremony — the formal mark of starting the school year — is one of the early memories that stands out. In the ceremony, which was considered a child’s entry into the outside world, a young Pingru traced lines of characters dedicated to Confucius with his uncle’s help. We also learn that, from early childhood, he was expected to fill his parents’ bowls with rice at every meal. These were two lessons from his parents that he never forgot: to value any paper with writing on it and to respect and value food so that not even a grain of rice would go to waste.

We also get brief insights into the gender norms in China. When he was young, Pingru’s mother taught him the right way to wring his washcloth (clockwise with right hand on top and left hand below) because women did it the opposite way. Meanwhile, on Meitang’s way home from school, a short length of the walking track was painted with coloured footprints to help girls learn how to walk gracefully. Meitang used to walk that path, hoping that she would grow up to be a graceful Chinese woman. We also learn that Meitang was very strong-willed and rather competitive as a child and, perhaps, it was these very qualities that helped her face the long years of suffering she would encounter later.

Striking paintings and poignant prose bring to life the true story of a young couple’s struggles through 20th century China

Pingru describes the cultural milieu of rural China, before the Second Sino-Japanese War, in striking detail. The festival that children enjoyed the most was the Chinese New Year and preparations for it began a month in advance: the house was given a thorough cleaning, meats and fish were salted and cured for the upcoming feast and every member of the family got new clothes. He tells us how, on the evening of the 23rd day of the 12th lunar month, they paid their respects to the kitchen god by lighting incense and candles and scattered rice and straw for the horse of the kitchen god, who would ride to the heavens every year around this time to report to the Jade Emperor, after having carefully observed the family’s behaviour in the kitchen through the year. The Jade Emperor is the supreme deity in Chinese mythology and is considered to be the first emperor of China.

The book presents a wealth of information about China’s traditional and regional food — from the mooncakes of Nanchang City, to tiger-skin duck and cassava meatballs from Nancheng County, to water chestnut cakes from Shanghai — and how certain dishes were prepared and what the expected rules for eating them were.

We also get a glimpse into the concept of ‘heat’ attributes of different foods in traditional Chinese medicine. According to the Ying and Yang division of food, certain foods are hot — for example fried and crispy meat — whereas some foods are cool — such as greens and tea. A healthy diet consists in balancing these two to keep the body neutral. As a child, Meitang would only eat “hot foods”, as a result of which her “internal heat” increased and she had to be taken to the doctors. We also learn about curious cures from Chinese medicine, such as powdered deer antler, which was supposed to be a powerful health supplement. There are precautionary tales as well, such as about Meitang’s older sister who became mute after an overdose of powdered pearl.

When Pingru was 16, the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out and his family was forced to move from their home in Nanchang City to their hometown Nancheng County where Pingru continued his studies. He joined the army when he turned 18 and, before he graduated from the military academy, his mother passed away. This is just one of the many sad events that Pingru witnessed in his long, but troubled life. However, although he lived through one of the most turbulent eras of modern Chinese history, he doesn’t dwell much on the politics of his times. Yet, readers can get revealing glimpses into what life would have been like during the civil war that followed the Chinese victory over the Japanese.

The war ended when he was 25 years old. Pingru had fought under the nationalist government of China, called the Kuomintang, or the KMT, but soon civil war broke out between the Kuomintang and the Communists. If earlier they were fighting a known enemy, now they were expected to fight their own people, when all they wanted was for the war to end so that they could be with their loved ones.

Following many years of unemployment and despite a temporary respite when he moved to Shanghai with his family and found decent work, there was still much suffering in store for Pingru and Meitang. As the political situation grew grimmer, many Chinese families were torn apart. In 1958, Pingru was separated from his family and taken to a “re-education through labour” camp, where he would spend the next 22 years doing physical labour.

But Pingru spends most of the book on his childhood and early days of marriage and does not say much about these 22 years. Instead, he focuses on how his family became destitute and were stigmatised because they would not sever ties with him.

When they got married, all Pingru and Meitang wanted was a quiet life, but little did they know that the China of pastoral beauty and tranquillity would soon be swept away by the winds of war and modern technology, never to return. At times, it is rather hard to keep reading the book because the sheer unfairness of life weighs heavy throughout this simple story of the life of an ordinary couple. Most of their dreams and wishes never came true: “Her desires were simple but they were destined never to be fulfilled.” However, it is a moving portrait of a marriage based on mutual love and respect and the paintings make the story all the more compelling. It really makes you marvel at how strongly emotive ordinary life can be.

The reviewer is an Ankara-based freelance writer

Our Story: A Memoir of Love and Life in China

By Rao Pingru

Translated by Nicky Harman

Pantheon Graphic Novels, US

ISBN: 978-1101871492

368pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, July 5th, 2020

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.