It is not easy for Iqbal Hussain to accept his freedom.

He is still getting accustomed to spacious rooms with comfortable charpoys to lie on; a courtyard where the family’s chickens cluck merrily as they skitter about; and, at night, the silent, open skies, so vast and endless, it makes him question his very existence. The night sky is the only familiarity that has stayed with him.

Death is always inevitable in life — although the teenage Iqbal did not think about this too often. But during the two decades he spent on death row, with his execution stayed twice, the inevitability of death only became more real, and the only torture that was afflicted upon him was that of hope itself.

Yet when Hussain walked out of prison — the heavy metal gate clanging close behind him for the last time — he tried his very best to ‘fit in’ the world outside. He walked out proudly, being heavily garlanded in bright paper flowers, smiling broadly at the dozens of relatives, lawyers and media teams that were there to receive him back into the free world. He had taken great care to comb his hair neatly and wore a crisp, white shalwar kameez. He was finally among humans, among people with full lives, living outside the prison fortress.

They have all been happy to see him; some out of affection, others out of a vulgar curiosity to see the man who cheated death. Even a week after his release, there are guests coming to visit him. They sit outside at a dera, sipping cold drinks and smoking cigarettes.

But, for Hussain, the streets leading to his home are no longer familiar. What has remained the same is his own decrepit little house, falling apart, as all the money earned from the family’s crops were spent on his legal battle.

Two decades on death row is the sentence Iqbal Hussain suffered for a murder he says he did not commit. Now that he is finally back home, how does he begin life again?

It is a sunny and humid day in the village of Mianwal Ranjha in Mandi Bahauddin when I go to meet him, though rain is on the cards. Four charpoys are placed beneath the generous shadow of a tree and two huge dogs roll about in the wet mud, their tongues hanging out. A pedestal fan whirrs to the side. The dera where Hussain greets his guests is a run-down affair — it looks like it is under construction. Next to it is a cowshed where some buffalos stand chewing fodder.

Before Hussain walks out to sit in the dera, there is a murmur of conversation. His brother-in-law and nephews speak in soft, concerned tones about Hussain and how much he has suffered at the hands of the police and the law. How the others accused in the same case were given life sentences and later freed after their sentences were over but Hussain, the youngest and a minor, had had a death sentence slapped on him.

Inside the house, the women are wearing smiles, happy that Iqbal is back. It is filled now with nieces and nephews who were not even born when their uncle was arrested. Today, they are all grown up.

Twelve-year-old Aqsa whips out a cell phone and runs a blackened thumb over its faded keypad. She shows pictures of her chachu (paternal uncle) coming out of jail. “We are so happy to have him here,” she says. “I have seen him for the first time.”

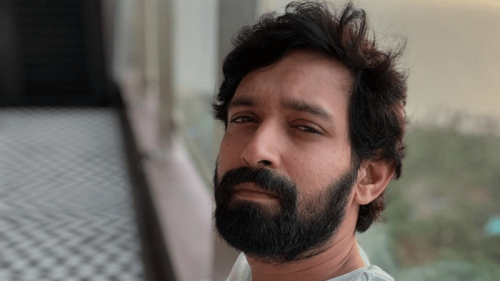

Aqsa’s elder sister has made a jug full of milk and soda for Hussain to quench his thirst, which he does as soon as he comes out of the shower. He is already living a luxurious life, he chuckles at them, and then walks out to the dera. Hussain may be laughing and joking but his eyes are wary and silent. There are lines underneath them and, in them, the hollowness of empty pits. His brow is furrowed and his face wears a haunted look. Still, he appears to be an approachable man, 39 years old now, with a slightly childish air about him.

For Hussain, it was the police station where his problems started when he was 17. Upon someone’s behest, his name was floated as a suspect for a murder case, along with four others. He was brought in for ‘questioning’. What actually happened was different. In an old government rest house, he was tortured for eight days. He emerged from that rest house bearing cuts, bruises and swellings. His very spirit had taken a beating too.

“I still feel angry when I think about it,” Hussain says of being arrested for a murder he says he did not commit. “But then I think of how much effort it has taken for me to come out here and I try to push away this feeling.

“The police tortured me in every way they could,” he says, every inkling of a smile suddenly evaporated from his face. “From strappado [the victim’s hands are tied behind their back and suspended by a rope attached to the wrists, resulting in dislocated shoulders] to the roller method [rolling a heavy object over the thighs as the victim is sitting, resulting in muscle damage], from tying my limbs on a charpoy, to mental torture, they did it all.”

I was in Mandi Bahauddin Jail when I was told that the president had rejected my appeal and my black warrant was out. I instantly felt sick and dizzy, knowing my life was about to end. But rejection upon rejection had made me understand that death was the only way I could leave this prison. I had accepted it.” What made it worse, however, was that he was first shifted from Mandi Bahauddin Jail to Gujrat Jail, where he was kept in isolation to await his hanging.

Then they blackmailed him. If he did not confess to the murder, they told him, they would nominate his father in the FIR.

“So I confessed that I did it. But in reality it had absolutely nothing to do with me.”

Even the magistrate did nothing when Hussain complained to him about the torture. It was 1998, says Hussain, the attitude was that violence should be expected in police custody.

But the result of this forced confession was that a 17-year-old Hussain ended up on death row — for 22 years.

IN PRISON TIME PASSES SLOWLY

When he entered jail, Hussain had no idea what it meant to ‘wait’.

For the first 10 months, he waited in hope for the court to decide whether he could be released because of his age. But the Gujranwala anti-terrorism court (ATC) issued him a death sentence under the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA), even though he was a minor. It was a sentence that could not be commuted, and he was sent to a death cell in the Gujranwala jail.

In 2000, the Juvenile Justice System Ordinance (JJSO) was promulgated, under which no minor could be sentenced to death. In 2001, the government issued yet another presidential notification that converted the death sentences of all minors into life imprisonment. But Hussain’s appeals in the Lahore High Court and the Supreme Court against the original ATC verdict were both rejected.

Even a mercy petition to the president was fruitless.

Then in 2004, in a surprising twist, Hussain’s family reached a compromise with the complainants in the case.

Waheed Ahmed, the son of the murder victim, explained this turn in an earlier interview. “Initially, times were hard after my father was killed, and we did not want to spare the culprits. But later, we decided to forgive him. It is important to forgive. We believed he had been punished enough.”

But the court rejected Ahmed’s statement and declared that Hussain’s matter was non-compoundable.

In 2008, the PPP came into power and placed a moratorium on the death penalty. Hussain was protected from being hanged until the subsequent PMLN government removed the ban in 2014, after the Army Public School terrorist attack.

In 2016, then President Mamnoon Hussain rejected Hussain’s mercy petition after it had been left pending for 13 years. For the first time, Hussain’s death warrant was issued. He was scheduled to be hanged on March 30. Justice Project Pakistan (JPP), a human rights organisation that provides legal representation to vulnerable prisoners, then took up his case.

“Death stared me in the face,” says Hussain. He looks distant, as if he has withdrawn into a private moment. Over the years, the former death-row inmate has developed a nervous habit of shaking his leg. From time to time he does this, belying his outward calm, signifying a deep anxiety within. Perhaps that is what a death cell does to a person.

For Hussain, it was the police station where his problems started when he was 17. Upon someone’s behest, his name was floated as a suspect for a murder case, along with four others. He was brought in for ‘questioning’. What actually happened was different. In an old government rest house, he was tortured for eight days. He emerged from that rest house bearing cuts, bruises and swellings. His very spirit had taken a beating too.

And what about that death cell? “It’s an eight by 10 cell… the bathroom area is also inside” he says. “There were around eight to 10 people inside when I first came. We used to lie next to each other, without being able to move. If I went to the bathroom, I could never find my space again. You can’t sleep straight, only sideways — every person gets only 17 inches of space. Motor function and muscular problems are common. But I have spent time alone too,” he says pensively. “For many years, it was just me in that death cell.”

Coming back to the present, he gives a little laugh to break his dark reverie. “This morning I woke up to do a little exercise, and some work in the fields but was left panting in a matter of minutes. I was hardly able to stand. By being stuck inside [a cell], your body just loses its strength and becomes useless. You don’t feel hungry either.”

BLACK WARRANT

“Jail is hell,” he says simply. “When I used to go out in the jail van, I used to see people going about their business. It seemed like a different world. Barra shauq honda si... [I wished I could be out there too].”

Instead, Hussain stayed in the same place for years with the same people. No one had anything new to say anymore. “You start getting irritated with the others if they don’t listen to you,” he explains. “But the fact is they have already heard you a million times.”

Studying and praying were the only two things that offered some little hope. He prayed for forgiveness. “A child learns from the world,” he says. “My world was the jail. I learnt everything in there. I studied in jail, did my matric from there too.”

But he did make some friends there, some of whom he is still in touch with.

“There was one very good man, Muneer Ahmed, who taught me how to read. I will always remember him as my ustaad [teacher]. But he was hanged in 2007. When his death call came, it was a terrible moment. I stayed up all night,” he shakes his head sadly. “In the morning, my mind was in a whirl. You break bread with a friend, and then some policeman comes, saying, ‘Aja tu…tere black warrant jaari ho gaye’ [Come, your black warrants have been issued]. When on death row, who even eats? You are aware constantly that your life is made up of just a few moments.”

Hussain cannot hide his anxiety reappearing as he speaks about his own death warrant being issued. His smile disappears. He swallows hard as he says that he was left alone inside a separate cell as he awaited his hanging, five days before his date of execution. His family had already come and met him for the last time. There was crying and regrets, grief and disbelief. After they left, he was all alone, their voices echoing in the empty cell.

He mops his forehead.

“I was in Mandi Bahauddin Jail when I was told that the president had rejected my appeal and my black warrant was out. I instantly felt sick and dizzy, knowing my life was about to end. But rejection upon rejection had made me understand that death was the only way I could leave this prison. I had accepted it.”

What made it worse, however, was that he was first shifted from Mandi Bahauddin Jail to Gujrat Jail, where he was kept in isolation to await his hanging.

“First they checked the cell properly to see if anything was left behind,” says Hussain. “They took away the cord from my shalwar and gave me an elastic. Then the doctors came to do the medical test. They checked my weight, they marked my neck and measured my height. That’s when reality really hit me. The end was near.”

In a miraculous turn of events, Hussain’s hanging was intercepted by a stay order. He could not believe it fully because he was still kept in the same death cell.

A man who is awaiting death should not be left alone in that death cell, says Hussain. “He should be kept in a separate place under the custody of the Supreme Court or High Court, where he can relax. At four in the morning, when it was time for my hanging, I was alert, even though I was told my execution had been stayed. I thought my time had come. I only believed the stay order was for real when the sun had risen and the time for my hanging had passed.”

Hussain spent many more years lying in wait for a death that would not come, yet would not let him live either.

But in February 2020, in a landmark judgment, Hussain’s death sentence was commuted by the Lahore High Court and, on June 30, he was released on the basis of his having completed his life sentence.

“I just remember I was an ordinary child before coming to prison,” Hussain tells me. “In jail, I used to dream of driving a truck in some other country. The constables that were there when I entered jail became inspectors in front of my eyes. Yet my life remained the same.”

Hussain has stepped into a new world, one where a pandemic has taken over, and lockdowns are imposed. The world has become a jail too. He still does not trust the system enough to be completely carefree. He still looks over his shoulder; he still has bad dreams. But, he says, he is happiest when he lies beneath the open sky, looking up at the stars.

Hussain can either stay here and work his family’s fields or perhaps he would rather move away from all this mess. Either way, it will be just another uncertain road he will have to take.

The writer is a member of staff. She tweets @xarijalil

Published in Dawn, EOS, July 26th, 2020