Ahmadis on the run: Fearing death in People's Colony

BY MIRZA IQBAL

GUJRANWALA: A pall of fear hangs thick over Gujranwala’s now eerily silent People’s Colony. It has been weeks since an enraged mob set fire to five homes belonging to members of the Ahmadi community, resulting in the deaths of two girls and an elderly woman.

Since the ill-fated Sunday when the incident came to light, police officials have sealed several homes in the area and warily patrol the locality lest a similar episode erupts.

Like many stories that pertain to the persecuted community, it is difficult to find people who will speak to journalists without requesting anonymity.

It is no different in People’s Colony, where terrified residents from the community are desperate for their plight to come to a logical end, but afraid to be named for fear of being persecuted further.

Only the dead are identified, because they no longer have to live in fear.

Residents say they cannot return to their homes, and are too afraid to expose themselves for fear of being targeted by fanatics.

A 50-year-old resident on condition of anonymity told Dawn that he saved 13 members of the Ahmadi community when the rioters set homes ablaze on July 27.

“I helped them escape from the burning houses to a safe rooftop during the riot,” he said. “If I had not saved them, it would been difficult to protect them from the rioting mob.”

The biggest victim of this tragedy is Boota, an Ahmadi man who lost his mother Bashiran Bibi and young daughters Kainat and Hira. His pregnant sister who was visiting from the nearby village of Talwandi Musa Khan for Eid holidays lost her baby in the chaos and fumes during the riot.

According to a spokesperson of the local Ahmadi community, Boota is in hiding, for fear that he will meet the same fate as his family members.

Boota's neighbour Saleem and contractor Javed say the rioters were not from their neighbourhood. “We do not know where so many people came from,” they said, lamenting the loss of innocent lives.

They also said that Boota’s family had good relations with everyone in the vicinity, and there was no friction when it came to religion. They lived “peacefully”, one resident said.

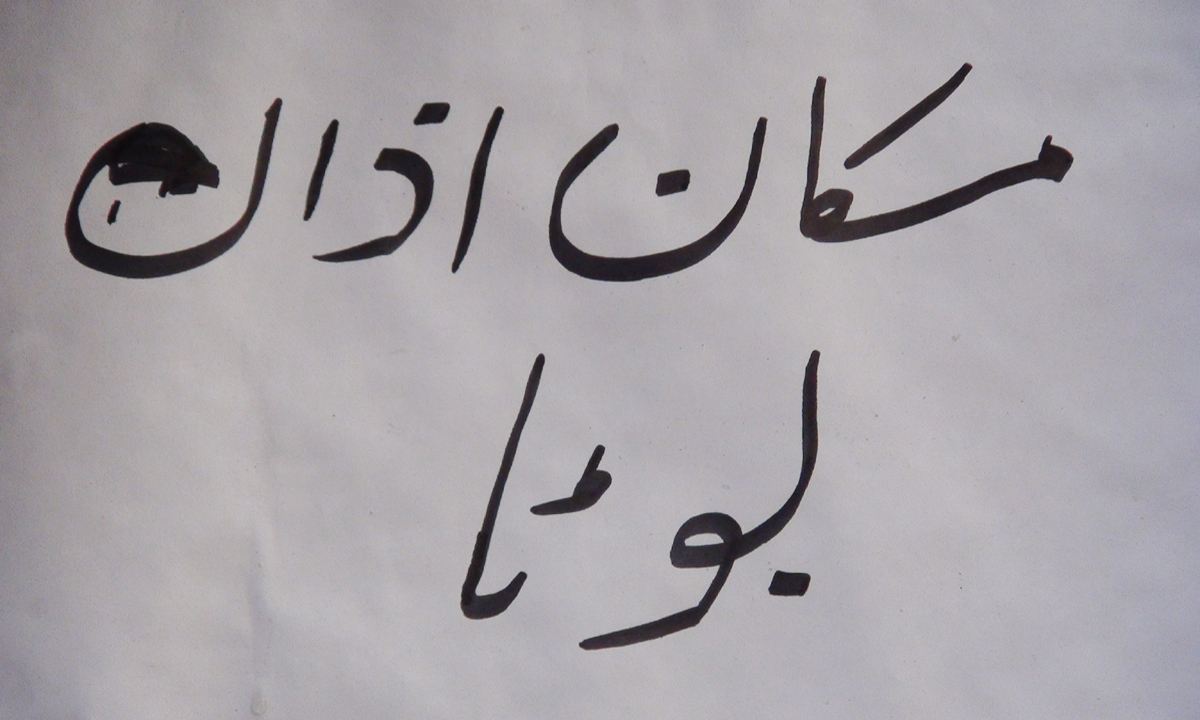

It all started, he continued, when a member of the Ahmadi community posted an "offensive" image on Facebook, which angered some residents of the area.

According to relatives, 18-year-old A* shared the image on Facebook with his friends on July 20. When news of this allegedly blasphemous photo spread, some residents communicated their anger to the boy. Residents say A soon admitted to posting the image.

The news spread like wildfire.

That is when the mob showed up and over the span of a few short hours, stormed and torched five of the 11 homes belonging to members of the Ahmadi community.

Police officials said a case was later registered by Boota against the rioters and a joint investigation team monitored by a senior superintendent probed the incident. Over a hundred “unidentified people” and six nominated persons were booked under terrorism and murder laws but no arrests were made.

A police official said a separate case had been registered against A and his friends for blasphemy.

He also said that the station house officer (SHO) of People’s Colony was suspended for his delayed reaction to the riot and the fire which resulted in the deaths. A show-cause notice was also reportedly served to the district superintendent police.

Finding safer ground

Religious differences are not uncommon in Gujranwala. According to Amnesty International, a man called Hafiz Farooq Sajjad was stoned to death by an angry mob there in April 1994 over the alleged burning of a copy of the Holy Quran at his residence.

In the same city, former Punjab minister for social welfare Zille Huma Usman was shot dead in February 2007 by a man described by the police as a religious fanatic when she was going to address an open court over her “non-Islamic dress”.

Several Ahmadi families have moved out of Pakistan since 1974 which was when the country declared the community non-Muslim. But the group has become particularly vulnerable since 1984, when Pakistan passed laws forbidding them from saying or doing anything associated with Islam.

The Baltimore President of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, Faheem Younus, says incidents like the People’s Colony attack force Ahmadis to leave Pakistan for safer ground.

“Whoever has the means to leave, finds it difficult to stay in Pakistan,” Younus tells Dawn.

In Pakistan, the Ahmadi question has also been about competition for economic and political power.

Younus says that “Ahmadis are worried about being used as scapegoats. Success for them has become a factor fraught with risks”.

He narrates the story of a relative who ran a successful business with franchises in Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad but was threatened to “back off”.

“Competitors openly threatened that they will falsely accuse him of blasphemy if he didn't cave in to their demands. He resisted for a couple of years. But then one of his own employees called a local maulvi, accusing that my relative offered congregational prayers at work [in Islamabad]. Two men came with guns, searching for him in his office. He left for Canada within months. Over 50 of his employees lost their jobs because be had to close the business.”

According to Younus, there are many tragic stories, “but there are also many Ahmadis who I know have the means, have the visas, but don't leave, can't leave either because of their love for the country or because they feel guilty leaving the rest of their family in Pakistan.”

He recalls that he was 13 years of age when the blasphemy laws were enacted.

“I'll never forget the look on my late father's face the day [the laws were enacted]. He said, you will see this will start with us [Ahmadis] but will end with the country's end.”

Photos by Faysal Mughal