ON Sept 29, Amnesty International (AI) India announced that it was forced to shut down operations. Executive Director Avinash Kumar said, “The continuing crackdown on AI India over the last two years and the complete freezing of bank accounts is not accidental. The constant harassment by government agencies ... is a result of our unequivocal calls for transparency in the government, more recently for accountability of the Delhi Police and the government of India regarding the grave human rights violations in Delhi riots and Jammu and Kashmir. For a movement that has done nothing but raise its voice against injustice, this latest attack is akin to freezing dissent.”

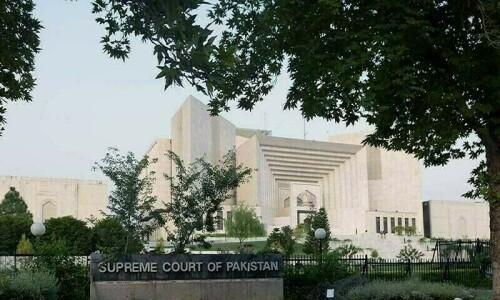

By sheer coincidence, on that very day, the supreme court asked the government’s counsel, “How long do you propose to extend Mehbooba Mufti’s detention? How long has the detention been for and on what grounds?” She has been in detention since Aug 5, 2019. It would, of course, have been more reassuring if the court had ordered her release. Habeas corpus petitions brook no delay.

The motives behind the crackdown are obvious.

International interest in Kashmir has declined. States have their own national interests. The void is filled by NGOs, especially AI in London, Human Rights Watch in Washington D.C. and the International League for Human Rights in Paris.

AI’s birth reveals the passion that drives it. It was founded by Peter Benenson, a British lawyer whose interest in fundamental liberties took him to places like Hungary, South Africa and Spain either as defence counsel or simply as an observer. In 1961, he read of two Portuguese students who had received seven-year prison terms for raising their glasses in a toast for freedom. He thought at first of lodging a personal protest with the Portuguese Embassy in London, but then had a better idea — now the core of AI’s technique — a chorus of protests from many sides.

Benenson, along with Eric Baker of the Society of Friends, set this idea out in an article entitled ‘The Forgotten Prisoners’ in The Observer (London). He announced the establishment of an office to work for the release of political prisoners, and expressed his readiness to help groups willing to join in this task. The response was overwhelming, and AI was formally brought into being.

Benenson’s book, Persecution 1961, reflected the breadth of his concerns. Among others, it set out the cases of prisoners of conscience, like doctor Agostinho Neto in Portuguese Angola; poet Olga Ivinskaya and her daughter in the USSR; lawyer Antonio Amat in Franco’s Spain; and writer Hu Feng in Mao’s China.

The release of prisoners of conscience, defined as “any person who is physically restrained (by imprisonment or otherwise) from expressing by words or symbols any honestly held opinion and who does not advocate violence”, is a central concern of AI. And so, each group ‘adopted’ the cases of three prisoners of conscience, one each from different parts of the world, to work for their release. A salutary peculiarity of AI’s working rules is that a group or national chapter may not adopt prisoners in its own country.

The group writes to the embassy of the government concerned and, if possible, discusses the case with someone in authority there. It writes also to the minister or official directly involved with the imprisonment, and secures the interest of any international organisation concerned with the prisoner. Finally, it keeps up a regular press campaign about its efforts for the prisoner’s release. The last is most important. As Maurice Cranston wrote in Human Rights Today, “If a man is in prison for his opinion, it is of vital importance that the world should know about it.”

AI grew rapidly. It widened its mandate, enlarged its organisation and reach. It has consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council and the Council of Europe, and maintains close links with the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, International Peace Institute and International Commission of Jurists.

Inevitably, AI drew criticism and attacks. Its publication AI in Quotes reproduced the calumnies by despots like Pinochet and Idi Amin as well as Indira Gandhi’s diatribes. AI performed a fair role all through the bogus ‘emergency’ imposed in 1975. Indira refused permission to an AI delegation to visit India. Pakistan allowed a mission to press for the release of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1971. As for impartiality, AI did splendid work on Northern Ireland during the Troubles, and published reports and legal studies on repressive laws there. Reports on Kashmir unfailingly censure wrongs committed by militants.

Centuries ago, Solon, asked how a people could preserve their liberties, said, “Those who are uninjured by an arbitrary act must be taught to feel as much indignation at it as those who are injured.” This is the core of AI’s beliefs.

The writer is an author and lawyer based in Mumbai.

Published in Dawn, October 10th, 2020