Victor Hugo Morales wasn’t even born in Argentina. He spent the first half of his life in his native Uruguay, and only moved to Argentina well into adulthood — a decision he would later put down to the persecution he felt from Uruguay’s military dictatorship of the time. Yet, over the past week, he has been cast in the role that he had through the final quarter of the 20th century: the voice of a people.

In particular, his ode — delivered in real time, and later referenced multiple times in the subject’s autobiography — to the most famous goal in football history, from a 1986 World Cup quarter-final, has gone “viral”. The passing away of Diego Armando Maradona on November 25, 2020, has meant that Morales’ paean had to be revisited.

It took barely 70 seconds from his enthusiastic exclamation of “Maradona has the ball,” to his emotionally raw bellowing of “Thank you God! For football, for Maradona, for these tears, for this… Argentina 2 England 0.” And yet, in those 70 seconds is a lifetime of bliss for a people.

It was not merely a goal, or a victory in the World Cup — it was so much more. It was a reminder of what sport can be — not a corporate exercise of billionaires’ playthings, nor just a stage for the best in the world to showcase their talents in unequal contests. At its best, it’s the revenge of the oppressed, the rare instance, in an entirely unequal world, for those with nothing to find themselves on a level playing field with the haves, a chance for an uncommon victory, but one that is a reminder of why life is worth living.

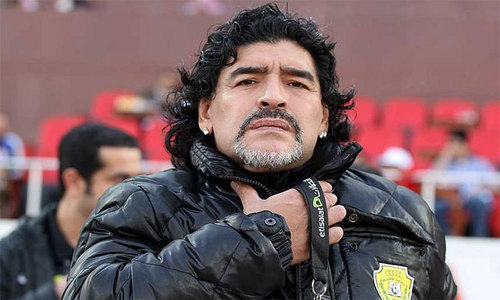

The unexpected death at age 60 on November 25 of Argentine Diego Armando Maradona, one of the greatest footballers the world has ever known, was mourned around the world. But it wasn’t just football fans who mourned him. To understand why, one has to understand what El Diego represented beyond the beautiful game

There is no currency to buy happiness, there is no metric to calculate joy in, there is just the feeling that exists, which eases the passage of time, and is the seed of the tree of nostalgia. That win could not change hundreds of years of imperialism suffered by the Argentines, much of it thanks to the British, nor the humiliation of the Falklands

War, but it was a confirmation of the humanity, and equality of the downtrodden. With the obvious exception of boxing great Mohammad Ali, there has never been a sportsman who was a better personification of all this than Diego Maradona.

A hero to the Global South

In 2002, Roberto Perfumo, perhaps the best Argentine player between the eras of Di Stefano and Maradona, put it succinctly, “In 1986, winning that game against England was enough. Winning the World Cup that year was secondary for us. Beating England was our real aim.”

A few years later, Calle 13, a musical duo of Puerto Rican independence (and anti-imperialism) activists, wrote the Grammy-winning song “Latinoamérica” as the anthem of their region; in that song the only reference to sport almost seems shoehorned in, but feels wholly appropriate:

The most beautiful faces that I ever met

I’m the photograph of a missing person

I’m the blood running through your veins

I’m a chunk of this soil that is worth it

I’m a basket with beans

I’m Maradona against England… scoring 2 goals.

I’m what holds my flag

The backbone of the world is my Andes

I’m what that my father taught me

“Who doesn’t love his motherland, doesn’t love his mother”

I’m Latin America

With broken legs we still walk forwards

Maradona’s death exposed the faultlines of all he represented — a hero not just to Argentines or Latin Americans, but to the entirety of the Global South; at once compared with players before and after him, but still seen by his devotees as someone beyond compare. To understand Maradona through his football alone would be a disservice to him, his disciples and even his detractors.

There’s a reason why the Washington Post obituary of him was more negative than what they had for even George H.W. Bush, or why the first paragraph of the Daily Telegraph’s obituary included the following line: “In a career never lacking in drama, he also proved himself a liar, a cheat and an egomaniac.” Even after he had taken his last breath he was living, rent-free, in the minds of those he hated, and those who hated him.

Ostensibly his numbers don’t really stack up to the other football GOATs (Greatest of All Times) of the past and present. An objective summary of his career cannot paint the picture of who he was, or why he is more beloved than perhaps any sportsman in history.

It would go something like this: born and raised in the poverty of Bueno Aires, he went on to represent Argentinos Juniors as a teenage wunderkind, before becoming the top goal scorer in back-to-back domestic seasons in Argentina, culminating with winning the domestic league with his beloved Boca Juniors.

Then he moved to Europe, and two years and a trio of cup wins with Barcelona were followed by seven years, two league titles, one Italian Cup and a European trophy at Napoli; before his personal life bled into his professional life, he was banned from the game and returned, with seemingly insignificant cameos at Sevilla in Spain and back in his native country with Newell’s Old Boys and, finally, at Boca Juniors again. He also represented Argentina in four World Cups, winning one and finishing runners-up in another. On the surface of it, there might be a couple of dozen players through football history who could challenge that career.

His trophy cabinet pales in comparison to the likes of Brazilian Pelé, Argentines Di Stefano and Messi or Portugeuse Ronaldo; and his influence on the game that followed him cannot be compared to the Dutchman Cruyff or the German Beckenbauer. His individual numbers could be seen similarly — while the likes of Pelé, Hungary’s Puskas, Messi and Ronaldo have all scored in excess of 600 professional goals, Diego finished at barely half that number. And yet, in a summer in Mexico, he did what no one else has ever done successfully. Maradona’s legacy asks the question if all trophies and goals are created equal, or if some goals are more equal than others, if some triumphs are to be elevated based on the supporting cast, or the lack of it.

Cristiano Ronaldo won six league and Champions League titles at Real Madrid, but it’s unlikely that Real Madrid will name their stadium after him. Pelé won three World Cups yet, by 2014, he was being proclaimed as “the traitor of the century” in mass protests that swept through Brazil that year; a fate that El Diego, for all his travails, was never likely to face. He played less than a dozen games at the tail-end of his career for Newell’s Old Boys, but even in such a short time he left something behind. When Leo Messi scored a goal last weekend, he took off his Barcelona shirt to reveal a number 10 Newell’s shirt in tribute (Messi is a lifelong supporter of Newell’s and joined their youth team the same year Maradona represented them). With Diego it was never about the amount of time he stayed at a place but the value of it.

Maradona’s post-playing career too set him apart. While the likes of Pelé and Frenchman Platini have spent the past few decades hobnobbing in corporate boxes, being the face of one superclub or football association or another; while Johan Cruyff and Beckenbauer spent their middle age becoming successful coaches and fighting boardroom battles, Maradona was always there with the only people that mattered to him — in the midst of the masses. In the middle of La Bombonera [Buenos Aires’ football stadium in its La Boca district], holding mass and living his best life, the Pakistani equivalent would be if Imran Khan had retired in 1992 and had then spent the following three decades doing what Chacha Cricket does.

Sure, Diego spent parts of the past decade attempting to become a football coach, but that obviously had more to do with him needing a purpose in a life that had gone off the rails, rather than any attempts to forge a greater legacy or impart innovative ideas.

Understanding Maradona

To understand Maradona, you have to understand what birthed him. Born in the squalid slums of Buenos Aires, his parents were rural immigrants to the big city — a journey taken by millions across Latin America in the 20th century.

Argentina in the 1950s was a country reckoning with the inequality of a broken society — the migration of Maradona’s parents was facilitated by the programmes of Eva Peron, the other great icon of the Argentine masses in the 20th century. It was a country that was the preeminent destination of Nazis escaping Europe, and one which could also produce a revolutionary like Che Guevara. Every country’s narrative-makers love to talk about the “extremes” in their society, and yet perhaps Argentina in the middle of the 20th century is incomparable to any in that regard.

The Argentina that Diego grew up in was similarly politicised. Gone were the days of Evita (Eva Peron); instead, they had to deal with Condor. Operation Condor was a CIA-backed campaign of repression and state terror across South America in the 1970s and 80s. Maradona made his senior debut as a 15-year-old in 1976, he left Argentina for Barcelona in 1982; those years coincide almost exactly with the Guerra Sucia (Dirty War) inflicted by the American-supported military junta of Argentina.

From 1976 to 1983, the junta “disappeared” up to 30,000 opponents of the regime, mostly leftists and Peronists. In 1980, the Argentine military allegedly helped Klaus Barbie, a Nazi war criminal, launch a successful coup in neighbouring Bolivia. It’s a period that Argentina is still reckoning with — to imagine that a man of the people would not be radicalised by this is to fully drink the reductionist Kool-Aid of the separation of politics and sports.

Thus, it is completely logical that the only hobnobbing Maradona seemed to do was with the likes of Fidel Castro, Hugo Chavez or Evo Morales, and that you could still find him voicing support for the people of Palestine when few did, or to turn up to political events wearing T-shirts declaring George W. Bush a war criminal.

Maradona’s understanding of the world is defined by the Argentina he was born and grew up in. His connection with the oppressed, and his disdain for the oppressor is how he saw himself, including on the pitch. He was a representation of them, an avatar of everyone in the crowd. All 5 foot 5 inches of him, looking disheveled and quite clearly not European (his father was of Guarani native American stock). He looked like he could be from any street in Latin America, and from afar in most other places in the Global South. Which is why what he means to Argentina, or even other such societies, is different than what other great sportsmen mean to their countries, and also why the 1986 quarter final against England took him to a level that perhaps no other sportsman has ever reached. It may not be Jesse Owens’ golds in Berlin’s 1936 Olympics, but it’s closer to it than his detractors would ever admit to.

England is the personification of the colonial, of the oppressor — it controlled Argentina’s purse strings through most of the 19th and 20th centuries. There’s a reason why the club that Messi supports is named something as evidently Victorian as Newell’s Old Boys. And then there was the Falklands War, a reminder to the Argentines that, even in the last quarter of the 20th century, they were still not allowed to have what they considered rightfully theirs.

The two goals in that match are the embodiment of Maradona, of Argentine football and, one could argue, societies across the world. The first is a rejection of rules and norms set by those he felt were the oppressors, which beating them was worth going beyond the rules for; the second is a reminder that, even within their rules, he was better than them. When Victor Hugo Morales shed those tears it wasn’t just for a goal in a World Cup quarter final, it was with all this as the context.

Diego's devotees

This is why from Lyari to Dhaka, from Lagos to Durban, every World Cup for countries in the Global South is about the Argentine-Brazil rivalry. The latter represents the rise of Brazil in the 50s and 60s led by Pelé, a mostly non-white team playing the European game and besting them over and over again; a half century of generation upon generation of greats, that all the downtrodden can rally behind as “their” representatives; and against them isn’t the entirety of Argentina’s football history — the fans of Albiceleste in South Asia, the Middle East or Africa don’t root for them for Sivori, Pedernera, Kempes, Passarella or Riquelme; they root for them for Maradona.

In 2014, there were clashes between Argentina and Brazil supporters in Barisal in Bangladesh, leaving 11 injured — the argument which birthed this clash was over the legitimacy of Maradona’s ‘Hand of God’ goal. Perhaps there have been greater players than him, but all of them have fans, Diego has devotees.

Nowhere outside Argentina are they more fanatical than in the south of Italy. The relationship of the north and south is as layered as any colonial or domestic relationship. The Risorgimento (literally, “the Resurgence”, in this context the Unification of Italy in the 19th century) birthed the modern state of Italy, but it wasn’t as straightforward as a people uniting to form a country.

The people of Southern Italy did rebel and join Garibaldi for the cause of a united Italy and deposed their king, but the unification with the north happened as Garibaldi (in his hopes for a united Italy) handed over the south to Victor Emmanuel II, the king of Piedmont-Sardinia, with his seat in the northern city of Turin, who had conquered the northern half of the country. Over the following century and a half, Italy has been ruled from Rome, but run from the north, and southern Italians have felt as if they are colonised.

The second largest political party in the current Italian legislature is the right-wing Lega (originally Lega Nord), a party founded when Maradona played in Italy, formed as an alliance of northern right-wing parties that wanted autonomy or separation for Northern Italy from what they consider the lazy, welfare-abusing Southern Italians. It is in this environment that Maradona joined Napoli.

Game-changer at Napoli

Prior to his signing, Napoli had finished in the bottom half of the table in the previous two seasons. They had never won the domestic title (their best position was 2nd, which they had achieved only twice in 50 plus years), had won only two Italian Cups and never been to a European semi-final.

The Italian league was, by far, the best in the world, and in the era of a maximum of 2 (later changed to 3) foreign players allowed in the XI, mid-table Italian teams signing big name South American players was a more usual thing than we nowadays realise: Socrates, the captain of Brazil’s 1982 team spent his only season in Europe at Fiorentina; Toninho Cerezo, his midfield partner, played more matches for Sampdoria than any other club; Junior, the left back of that side and considered a precursor to modern fullbacks, spent five years at Torino and Pescara; the captain and the final goal scorer (Daniel Passarella and Daniel Bertoni) of Argentina’s 1978 World Cup final were both at Fiorentina together in the early 80s, yet they never won the Serie A title, just as the Brazilians never did.

Only Falcao at Roma (already a big club) managed to win one league title among all these South American imports. The problem was that you could buy the odd world class South American, but the best local players were all tied up with the big Italian sides of the north, meaning that all these imports had to compete with lesser quality than the big clubs. Thus the expectation from Maradona would have been the same, another South American import at a mid-table club, who would leave with memories but little silverware.

1986/87 was Maradona’s third season at the club, immediately following his glorious summer in Mexico. If he could lead an Argentina side with no other world class players to the World Cup, perhaps he could do the same with Napoli?

Juventus, the giants of Italian football and Napoli’s most hated rival (for political — considering they were Turin’s club — as much as sporting reasons) finished second that season; their team had four players that had already played for Italy at the start of that season, along with two world class foreign players in Michel Platini and Danish Michael Laudrup. Inter finished third with eight players that played for Italy by that season to go with two world class players in Argentine Daniel Passarella and German Karl-Heinz Rummenigge. Napoli finished top with three Italian internationals, and only one foreigner. Maradona and Napoli had history, talent, politics and a famously crooked league to fight against, and they overcame it all.

And it wasn’t a one off. Napoli’s Serie A finishes following that season until the 1990 World Cup read: 2nd, 2nd and Champions. The second runners-up season coincided with them winning their only ever European trophy — the UEFA Cup in 1989. After knocking Juventus out of that tournament in the quarter final, Napoli went on to defeat Bayern Munich and Stuttgart in the semi-finals and the finals. In those four matches (both ties had home and away legs) Napoli scored 9 goals — Maradona scored or assisted 7 of them.

The giver of joy and dignity

It ended in acrimony though — Maradona’s Argentina knocked out Italy from their home World Cup in 1990 and, in characteristic fashion, Diego opened wounds that had been built over a century, and his relationship with Napoli and Italian football deteriorated.

But time heals all wounds. As the years passed, Neapolitans looked back to the man that gave them joy and dignity, to a man from across the world who was one of their own. Thus, it was no surprise that, in the hours following his death, the city of Naples decided to change the name of Napoli’s stadium to the San Paolo-Diego Armando Maradona. As one Neapolitan put it, only one man could share billing with Saint Paul.

And that is his legacy — wherever he went, he didn’t have fans as much as devotees. The way he played, the beauty of it all, and the beast that wouldn’t ever be conquered. I haven’t talked much about the beauty, why the devotees fell in love at first sight, because to write about his beauty with the football in an era where the former Argentine player, coach and commentator Jorge Valdano can still write elegies to him, seems pointless.

Now though, Maradona’s gone, and we should celebrate him for all that he was. We will never see his like again.

CONTINUE READING: MARADONA OF PAKISTAN

The writer is currently the Strategy Manager of the PSL cricket team Islamabad United. Prior to this he has worked as a sports writer and commentator

Published in Dawn, EOS, December 6th, 2020