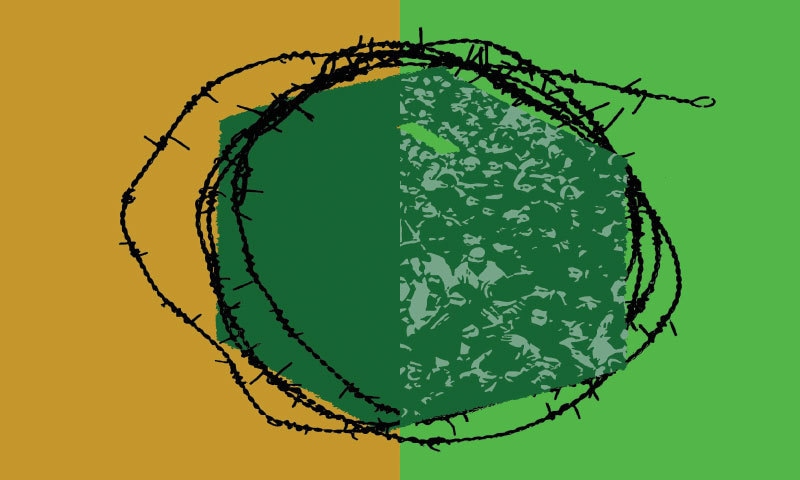

On December 13, the 10-party opposition alliance, the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM), held a large rally in Lahore. It marked the completion of the first phase of the alliance’s agitation against the Imran Khan government. This phase saw PDM hold anti-government rallies in six cities. The next phase includes a ‘long march’ towards Islamabad and possible resignations of opposition members in the assemblies.

Pundits and analysts are already out weighing the chances of both the PDM and the government. Heated debates are taking place about whether the opposition alliance would be able to dislodge a government that is already besieged by a faltering economy, rising inflation, a lethal pandemic and the government’s own blunders, which are many.

Most commentators are of the view that, even if PDM is unable to outright force PM Khan’s departure, it can create a serious constitutional and political crisis, which will not only bog down a troubled regime, but can also create issues for the military establishment that is overtly backing the present set-up in Islamabad.

The most worrisome aspect of this is that the military establishment has begun to be seen as a visible party in the conflict between the PDM and the government. The kind of political crisis the PDM’s agitation is expected to create can be detrimental to a highly polarised polity.

There have been five major anti-government movements since Pakistan’s inception in August 1947. The first such movement was able to force the military dictator, Ayub Khan to resign in 1969.

The second one managed to stall Z.A. Bhutto’s bid to rule as PM for the second time in 1977, but it also saw the imposition of the country’s third, and perhaps harshest, military regime. The third major movement was made up of a cluster of movements between 1981 and 1986, against the Gen Zia dictatorship. Even though intense and at times extremely violent, this movement failed to dislodge the dictator. He died in a plane crash in 1988.

The Pakistan Democratic Movement’s agenda is clear — to exhaust its opponents, so opportunities emerge to further expand and grow the movement. But it also needs the alternative vision of society that Nawaz Sharif is providing

The fourth movement rose up against the Gen Musharraf dictatorship in 2007 and succeeded in ousting him through a forced resignation. The last major anti-government movement was led by Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) against the third Nawaz Sharif regime. It was unsuccessful but it did manage to create enough space for PTI to squeeze through during the controversial 2018 elections.

The PDM has succeeded in holding impressive rallies. But it is still not a full-fledged movement. It is expecting to evolve into becoming one during its next phase. However, it is still too early to predict whether the PDM will succeed in removing the Imran government or, especially, if it can actually achieve its second, and more ambitious, aim to neutralise the self-appointed political role of the military-establishment.

Succeed or not, once the PDM does evolve into becoming a movement, there is every likelihood that things will begin to alter, for good or otherwise. In a 1973 essay for the Annual Review of Anthropology, the American sociologist and anthropologist Ralph W. Nicholas writes that political and social movements may have varying degrees of success (or, for that matter, failure) but they leave behind societies that are never quite the same.

Nicholas describes movements as ‘liminal’ or ‘the interim between the end of the old and the beginning of the new.’ According to Nicholas, movements may evolve into becoming successful uprisings, or they may be crushed but, no matter what the outcome, they always have what it takes to become contagious. He adds that they also have the seeds to become ‘successive.’ By this Nicholas means that even movements that are crushed or collapse become paradigms for future movements.

As long as there are conditions for a movement to emerge, they will, despite being repeatedly vanquished. According to the ‘political opportunity theory’, if a political system seems vulnerable, there will emerge challengers who would move to use this vulnerability as an opportunity to push for political or social change. The American political scientist and historian, Charles Tilly is often credited as being one of the foremost pioneers of the aforementioned theory.

The theory is not as much about why movements emerge, as such, but rather what course they take once they get going. Reasons behind the why, generally speaking, can be economic or to do with repression. Interestingly, the theory states that democratic pluralism too can become a factor.

For example, all these factors can be seen playing a role in the large pockets of protests emerging in India recently. An economic downturn, coupled with political repression and the country’s long-standing democratic systems, are allowing these protests to take shape, so much so that some members of PM Modi’s government are now lamenting that too much democracy is a problem. This could be understood as meaning that democracy is hindering their desire to fully implement the government’s contentious Hindu nationalist projects.

However, the theory is equally applicable in regions where there are economic issues and repression but too little or no democracy. The theory states that agitation against these or other issues brew in pockets that continue to expand even when these pockets are repressed. Their consistency eventually begins to sap the energy of the state and government and this creates opportunities for pockets of resistance to mobilise from within and outside their circle until they merge to become a movement.

Conditions for a movement in Pakistan are ripe. Economic meltdown, state repression, bad governance and political polarisation are now pitching one chunk of the polity against the other. The PDM’s agenda is thus clear — to exhaust its opponents, so ample opportunities emerge to further expand and grow the movement. But according to Nicholas, politics alone will not be sufficient. Disillusionment against an existing governing ideology needs to be replaced by a new promise to invigorate a disillusioned polity.

The anti-Ayub movement offered various forms of economic equality to inspire the people to come out and protest. An ‘Islamic’ system of government was promised by the movement to bring people out against the Z.A. Bhutto regime. The idea of tabdeeli (change) was floated by Imran Khan during his party’s street. And now Sharif is promising a democratic and political system that will not be rigged, engineered or tampered by a non-civilian elite.

Promising democracy alone would not have been able to draw the kind of attention the PDM has managed to attract. This promise needed a new angle which Sharif has provided.

Published in Dawn, EOS, December 20th, 2020