Land reclamation is a phenomenon not new to Karachi. For years, the city’s coastline has been continuously pushed back and mangroves destroyed so that the ‘newly’ created land can be sold and used for development, and researchers predict that the city is likely to sink by 2060 if this were to continue.

This exploitation of natural land is sure to have negative consequences and is something that artist David Alesworth reminds us of in his latest exhibition at Karachi’s Canvas Gallery. Titled The Carless Mapping, in reference to cartographer Lt. T.G. Carless, the display acts as an illustration of the consequences history has had on its present.

Alesworth, a British-born artist, has trained innumerable Pakistani artists during his decade-long teaching position at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture in Karachi. He is a sculptor, photographer and researcher of garden histories and has been working between Pakistan and the United Kingdom.

The artist’s work is inculcated with an understanding of drawing and explored through non-traditional mediums throughout the exhibition. The focus is an embroidered carpet titled ‘The Carless Kashan 1838’. Alesworth embroiders the map of ‘Kurachee’ created by cartographer Lt T.G. Carless for the East India Company, into a refurbished carpet that is already intensely woven. As a visual, the piece is serene; the curvilinear forms of the map flow with the organic imagery of its backgrounds and the white embroidered thread does not feel like an intrusion, which in fact, it is.

Alesworth explains that this was no innocent mapping by a foreigner of alien land, rather strategic planning ahead of military action. Soon after, ‘Kurachee’ was captured by the troops as they blasted present-day Manora and conquered with no resistance. The work is soft and intimate and greatly contrasts with its brutish narrative.

A striking exhibition delves into the past and the present of our immediate surroundings through the eyes of the British-born artist David Alesworth

As part of the Khushab Residency in 2018, Alesworth created large ephemeral drawings within a bed of bituminous coal and limestone dust. These 300-foot shadowlike creations were documented, titled ‘Drawings In Time’, and were representational of the prehistoric plants species that were likely responsible to for the very same fossilised fuel reserves that they were carved into. Again, the artist plays with the past and present in his work, intermingling them and allowing them to exist in the same space.

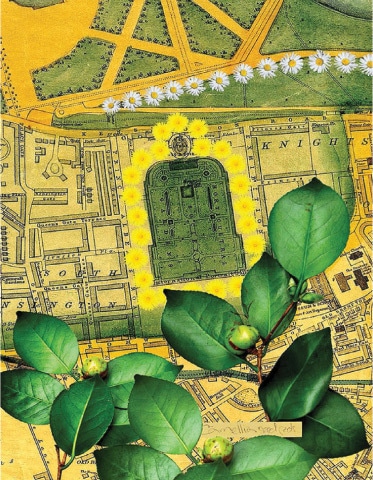

His work as an avid gardener and dedicated researcher comes through. ‘Gardening The Archive’ are a series of prints where he amalgamates his documentations of historical mappings and archives with images of his personal plants. But just like when anything is ever documented, there is a selection of what should be shown and what should be erased.

In the ‘Rosa Sub Rosa’ and the ‘Dark Rosa’ series, Alesworth uses visual erasure as a means of communicating. Here, flowers are stripped from their surfaces, leaving only a blank silhouette where they should be. The idea of displacement and seizure, much like how the ‘The Carless Kashan 1838’ narrates, also comes to mind where a supposed ‘unoccupied’ area is now come to use.

As a traveller between Britain and Pakistan, Alesworth is able to look at either space as an outsider. His works then become their own maps of sorts, as he traverses through time and location, and encapsulates the narrative much like a time capsule, or even a precursor of how history has a tendency to repeat itself, which he then explores through his fascination with horticulture.

“The Carless Mapping” was on display at Canvas Gallery in Karachi from December 1 to December 10, 2020

Published in Dawn, EOS, December 27th, 2020