THOMAS Carlyle had aptly remarked that history is actually the biography of men. Some of these men go on to become leaders. In that role they play a decisive part in the lives of people, nations, societies and the human race at large. Their views, thoughts and actions compellingly become the prime motivator, contributing either positively or otherwise to the march of the history of mankind. History has always and will always remain in the domain of the “art of imagination”. To use Carlyle’s words again, “history is a distillation of rumour”. There is hardly any space for anything like “objective history”; history relates to men, and, hence, it can never move too far from the element of subjectivity.

An unacknowledged quote about lessons in history was used by Martin Luther King, in his ‘Strength and Love: The Depth of Evil Upon Seashore (1981)’. In his words, there are four major lessons of history. “First, whom the gods [would] destroy, they first make mad with power. Second, the mills of god grind slowly but they grind exceedingly small. Third, the bee fertilizes the flower it robs. Fourth, when it is dark enough, you can see the stars.”

Living without a memory is equivalent to losing one’s ability to remain humane; amnesia could be a curse. A deliberate attempt to forget the past is a travesty to the concept of ‘sense of history’. Such people neither deem history to be an important teacher nor do they believe in creating one. All days get confined to the annals of the past, and no amount of wealth, power and resources can undo the deeds; noble or ignoble.

Individuals, particularly politicians, need to be obsessed with this reality. Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah had unwavering belief when it came to achieving his mission of creating a homeland for the Muslims of the subcontinent. No amount of cajoling and temptation to become leader of an undivided India lured him towards an alternative path. Nothing rocked his conviction to create Pakistan, and today we are enjoying the fruits of his labour, his awareness, and his acute sense of history.

Any discussion about Jinnah generally revolves around his role as a politician. The fact is that there was much in his personality that can inspire everyone aiming big. And that includes those in the corporate sector.

This single trait was deep-rooted in his persona. The trait is dependent, hence emerges from one’s upbringing and habits. This sense of history, with all its attendant implications, does not apply to politics alone. It encompasses every segment of life, including the corporate sector. Moving around the corporate world, one hardly ever hears of the Quaid as a leader of men. Even leadership seminars and workshops quote this thing or that from this person or that, but hardly ever quoted the Quaid. It happens simply because we have limited the Quaid to being a politician, which is so unfair to the leader of men that he was. There are many traits of Jinnah that are equally valid and applicable in the business and the corporate world.

Great leaders have to be necessarily good men, and Jinnah was first and foremost a good human being. He created and raised the bar of statecraft to a higher moral plane. On that count, he was mostly rigid, obstinate and uncompromising. Jinnah, despite his outward appearance as a typical English aristocrat, was not an elitist. He sincerely believed that only mass education could relieve the society of caste and class consciousness. He was not a socialist either, but cared for the welfare of the whole society.

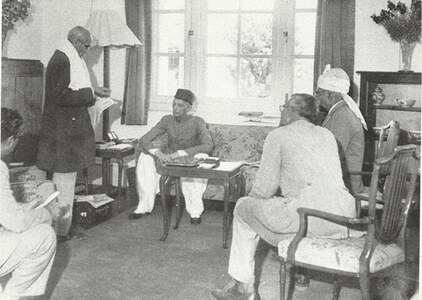

Planning, which is a major role of any corporate leader, was always the Quaid’s main focus. The Muslim League had a planning committee of scientists, entrepreneurs, academics, engineers, economists, etc. Addressing one such committee in November 1944, Jinnah had the following to say: “It is not our purpose to make the rich richer and to accelerate the process of accumulation of wealth in the hands of a few individuals. We should aim at levelling up the general standard of living amongst the masses”. By not following that vision, post-independence governments through their own planning and policy, instead, gave the nation the ‘22 families syndrome’. But that is another story!

Commenting on the importance of planning, inclusive of economics, he said: “Planning is a stupendous task pertaining, as it does to every department of life … we cannot of course prepare a scheme complete in all its details. The data at our disposal is inadequate for the purpose”.

Economic independence and wellbeing was close to his heart. Against all odds, and medical advice, he travelled back from Ziarat to Karachi to give the inaugural address at the opening of the State Bank of Pakistan. It is said that Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan repeatedly rose to go towards the Quaid, for he feared that Jinnah may collapse due to frail health.

The Quaid stood ground though. Belonging to the fraternity of bankers, I don’t even want to imagine what the Quaid would have thought of us – the propounders of benami accounts, falooda accounts with billions in balance etc.

The Quaid’s anxiety levels were at peak when his finance minister informed that the exchequer was empty. He was relieved when the Nizam of Hyderabad remitted a loan of Rs200 million, and Jinnah lost no time in publicly acknowledging the gesture. I know had Jinnah lived longer, he would have repaid the Nizam. In his mind, there was no concept of default on loan repayments. To gauge where we are, one may check how many and what amount of loans have been written off since 1947, costing ultimately to the state and the patriotic taxpayer.

Not long after independence, Pakistan lost both Jinnah and Liaquat, who were true leaders of stature. India was fortunate to have leaders from the independence movement who lived longer; Jawaharlal Nehru ruled till death for 17 years, alongside many others, who built upon the tradition of institution-building and good governance.

The malaise of corruption in every sphere of our national life is a consequence of the loss of our selfless leaders. For leadership, selflessness and its continuity is critical, regardless of whether it is the state, an organisation or a corporate entity.

Aloofness to a certain degree is a requirement of both the corporate and political worlds. Jinnah, wrote HV Hodson, the Reforms Commissioner, “was always a man of principle, but he was supremely a man of pride”. Distance and aloofness, as a habit, tend to convey a feeling of being proud. In Jinnah of Pakistan, Stanley Wolpert defended Jinnah thus: “… right to the extent of saying Jinnah was proud, but there is national pride and there is personal pride. Jinnah was not personally proud”. In defence, Wolpert quotes the following passage attributed to Jinnah having said, “I was considered a plague and shunned. But I thrust myself and forced my way through and went from place to place uninvited and unwanted. But now the situation was different”. There are many take-home points from this quote for young professionals; persistence, discarding vanity and possessing self-belief bordering on audaciousness in the pursuit of an objective are prerequisites for leadership positions.

Sarojini Naidu labelled Jinnah as the ‘ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity’ and Kuldip Nayar, in his book, suggested that it was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi who gave him the appellation of the ‘Quaid-i-Azam’. Against this backdrop, how did Jinnah transform to being the leader of the Muslims of the subcontinent? Today’s media, politicians and pseudo-analysts would have called it a U-turn, but that, again, is another story!

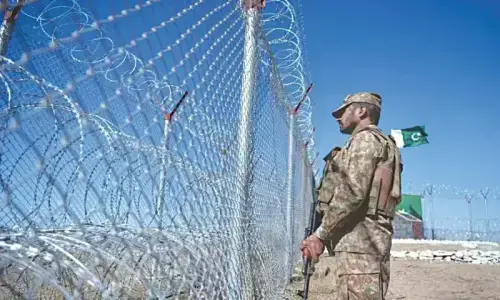

Jinnah was convinced that in undivided India, Muslims would not only remain second-class citizens, but would also be persecuted for the extended Muslim rule in India. The happenings in today’s India bear testimony to the authenticity of the Quaid’s understanding of the mindset. In business decision-making, we make numerous U-turns and there is nothing bad about it; if a wrong business decision has been made, it is best to recognise it, undo it and re-do it differently. That is called ‘experience’ by a positive mind.

Today’s India was predicted by Jinnah when in 1912, a year before he joined the Muslim league, he remarked at the Patna Congress meeting: It is Gandhi, he said, who was destroying the ideal with which the Congress was started. He was the one man responsible for turning the Congress into an instrument for the revivalism of Hinduism. What Jinnah foretold, and what Gandhi cunningly imagined, Narendra Modi has delivered. As a leader, there is an imperative need to have perceptive powers to forecast the events that are likely to unfold. This trait applies as much to market economics.

A corporate leader, say a chief executive officer, of any organisation is usually confined by the number of years he can hold office.

If the tenure is to last 3-5 years, should the CEO be framing policies that will hold and last good only to the extent of his tenure of engagement? If he were to do so, he would cease to be a leader. Individuals who lead others have to plant with acceptance the seeds of their efforts that will bear fruits not for him, but for generations to come. This requires sacrifice. And Mr. Jinnah sacrificed his personal life to achieve Pakistan; for us.

No personal grief, like the death of Ruttie, no personal disappointment, like the marriage of his only daughter Dina against his wishes, or ill-health derailed him from his passion for getting a Muslim homeland. Another word for leadership is selflessness.

Also, Jinnah was a thinker par excellence. Commenting on his precision of judgement, Manto says, “As in billiards, he would examine the situation from every angle and only move where he was sure he would get it right the first time.”

Jinnah in personal attitude was non-compromising and financial proprietary ranked high in his dealings. He neither befriended nor moved in the company of tax-evaders, smugglers, cheats, hoarders, unscrupulous businessmen, real estate tycoons, etc.

He took no gifts. He was frugal. He spent no state money upon himself. I hope someone in the corporate world is reading these lines. I also hope that the current lot of politicians, regardless of affiliations, are also reading these line, but that, once again, is another story!

Jinnah believed that the “first law of decency is to preserve the liberty of others”. He had no grey areas, and dealt in stark white or jet black. He suggested for himself a princely salary of one rupee per month as the governor-general.

The corporate leaders must hang their heads in shame at the vulgar amount of emoluments they take for much less work; both in quality and context.

Jinnah possessed dry wit, was always in control of himself, be it in grief or in happiness. And those who have it in the corporate world are bound to make it big. Will they? Well, that, yet once again, is another story!

The writer is a senior banker.